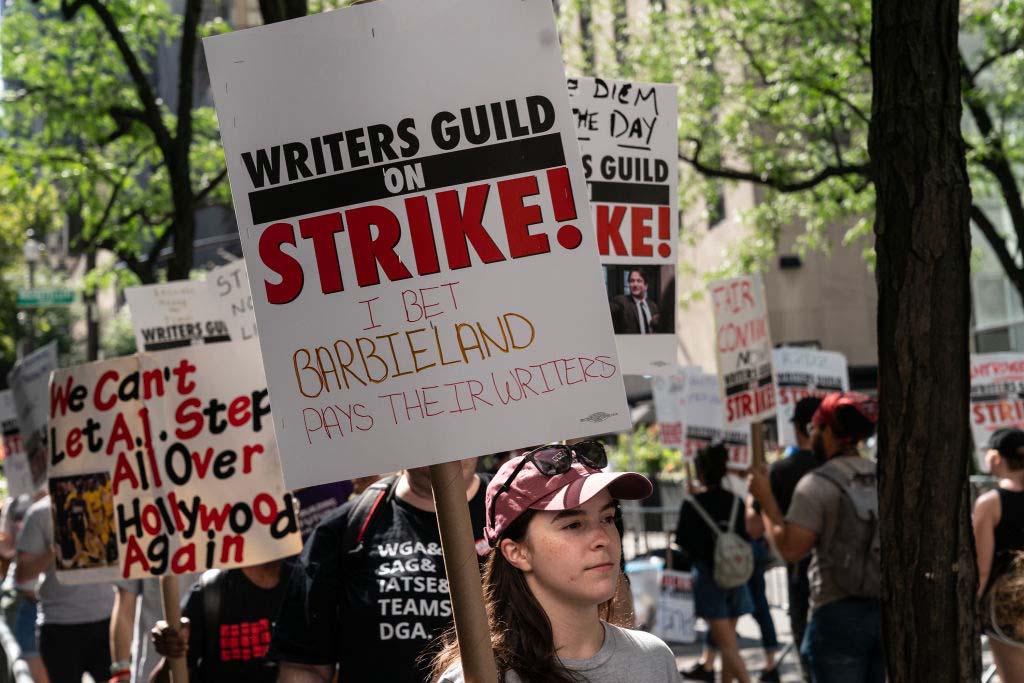

After almost 100 days on the picket lines with no signs of progress at all, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) revealed yesterday that the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) has “reached out to the union and asked for a meeting this Friday to discuss negotiations.”

The ongoing writers’ and actors’ strikes are having a devastating impact in Hollywood, where the economic pain is trickling down to behind-the-scenes, below-the-line workers and related service industries. The WGA estimated that the strike is costing California’s economy $30 million a day, but that was before the actors union, SAG-AFTRA, launched its own parallel strike July 14.

FilmLA recently reported that TV drama production in Los Angeles county fell by 63.8% in Q2, while TV comedies were down by 72% compared to the same period last year.

But while news that the two sides are willing to meet on Friday marks the first sign of progress since writers walked off the job May 2, it’s far from a major breakthrough. According to a report from Deadline, Friday’s discussions “are centered on creating committees to examine the issues. The topics at the top of the agenda include minimum staffing, duration of employment, a viewership-based streaming residual and AI.”

In other words, they’re just getting started.

The Penske trade pub reported last month that from the outset, the studios’ plan was to “let the writers go broke” before resuming negotiations in the fall, and that the studios planned to hold their breath until late-October before reaching a deal.

The publication cited one unnamed studio exec saying, “The endgame is to allow things to drag on until union members start losing their apartments and losing their houses.”

But the AMPTP is made up of both traditional studios and streaming giants like Netflix, Amazon and Apple and while they both make TV, they have very different business models and agendas.

Moody’s Investors Service recently estimated that in the end, settling with the unions could cost the studios as much as $400-600 million per year and added that a prolonged work stoppage would hurt traditional TV before big streamers.

“Television will bear the brunt of a long strike as the implications of the two striking unions will play out more noticeably for TV networks, stations, cable channels...“ Moody’s said. “TV networks, particularly broadcast networks, consistently schedule new primetime shows to begin in the fall. Cable networks vary in their exposure to original scripted content and, therefore, only some are exposed…”

But the analyst added that the least at risk would be global streaming platforms who are “well-positioned financially, have little or no exposure to the declining linear ecosystem and have diverse sources of content — both in terms of production and libraries.”

Indeed, studios with a linear broadcast business to maintain were left empty-handed entering this year’s upfront season where the TV networks try to pre-book ads for the coming year, especially during their buzzworthy new fall premieres.

Instead, they’ve been forced to rely heavily on reality TV for the fall season, largely contributing to a weak upfront sales market this year.

Netflix, meanwhile, recently reported that its nascent advertising initiative had no material impact on Q2 earnings, and with its international pipeline of new content and vast library, it was obvious from day one that the streaming giant was in the best position to weather a prolonged strike. Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos told investors on the company's earnings call that the streaming giant had upped its free cash flow estimates for the year by $1.5 billion due to lower content spending during the work stoppages.

Michael Nathanson, founding partner of SVB MoffettNathanson, recently told CNBC’s Squawk Box that the strikes play to Netflix’s strengths. “The problem here for the strikers is that it’s going to make Netflix stronger and their competitors weaker,” he said.

While most of the writers’ demands focus on monetary issues the widely-publicized paucity of their dwindling residuals, the issue of artificial intelligence in the creative process has emerged as a much more thorny topic in both strikes.

In May, when the writers walked out, the AMPTP put out a statement saying that AI technology, “raises hard, important creative and legal questions for everybody… Writers want to be able to use this technology as part of their creative process, without changing how credits are determined, which is complicated given AI material can’t be copyrighted. So it’s something that requires a lot more discussion, which we’ve committed to doing.”

At least, with the two sides finally sitting down at the negotiating table, they’ll be able to start those discussions.