“It’s both,” says pro wrestler Scott Colton, aka Colt Cabana. “It’s a genre unlike anything in the world.”

Cabana, who hosts the “Art of Wrestling” podcast, has been a professional wrestler for more than 20 years.

“Obviously, you have to be athletic, you have to be coordinated in order to perform these moves at the highest level,” he says. “But you also have to be entertaining.”

Pro wrestling has a history built on sacred oaths, sleight of hand, rigged matches, outsized personalities, headbutts and body slams. It’s evolved from its early days as a carnival sideshow to a billion-dollar industry.

And once, in the mid-20th century, Chicago played a starring role.

Age-old activity

Wrestling’s one of the oldest contact sports. Cave drawings thousands of years old show a remarkable resemblance to the holds and stances seen today in flashy televised bouts and organized school athletics.

In the early 1800s, well before he became president, a tall, lanky guy named Abraham Lincoln was an amateur wrestler in Illinois. He was a fan of the “chokeslam” and often dominated his opponents.

After the Civil War, wrestling took on some of the professional elements that underscore the sport-versus-entertainment question that still surrounds it.

“If you go back into … the late 1800s, the early 1900s … [wrestlers] had to travel around the country and usually be at a carnival or a small venue, like sometimes they were in taverns or bars,” says George Schire, a historian and author of “Minnesota’s Golden Age of Wrestling: From Verne Gagne to the Road Warriors.”

The carnivals, with their sword swallowers, fortune tellers and games of chance crafted to prey on gullible patrons, were the perfect setting for the athletic but often rigged wrestling matches.

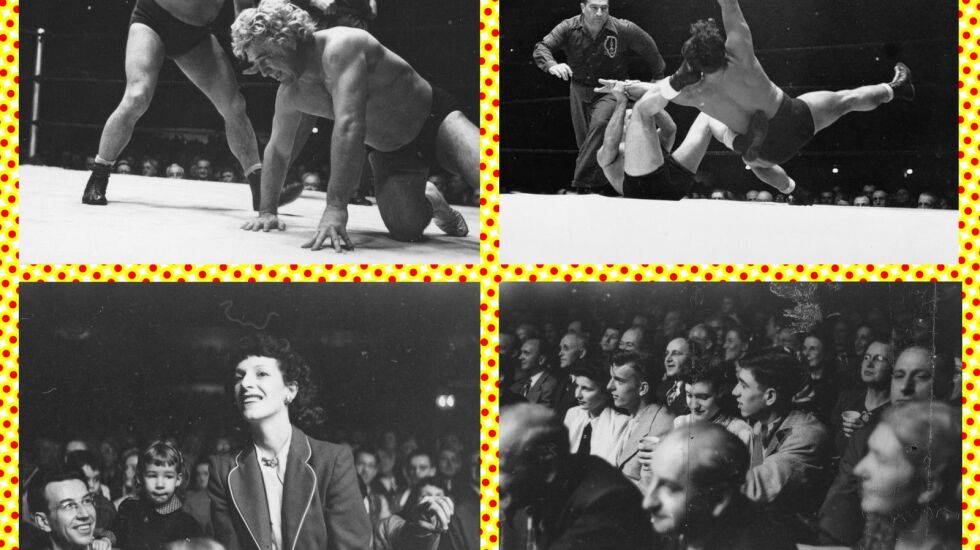

At carnivals, a wrestling bout usually involved two men locked in grappling holds and flinging each other around the canvas. It was a carnival sideshow of action and pathos that offered a distraction from everyday life.

There also was money to be made. But the price of admission wasn’t the only cash people would drop.

Carnival wrestlers often collaborated with other traveling wrestlers known as “barnstormers,” according to Scott Teal, a pro wrestling historian who publishes books about the sport. Teal says barnstormers would “go from town to town, and they’d send in guys ahead of time to start talking up the match.”

Schire says the idea was to create buzz and further tempt locals with prize money if they could last in the ring with these pro ruffians. They’d also want townies to lay down bets on their hometown hooligan or maybe on the burly traveling wrestler. Sometimes, they’d have a plant, perhaps a local farm kid who was there to wrestle and knew something the audience didn’t — that the outcome was predetermined.

It was show business. But it also was athletic. Because the wrestlers would take on all comers — not all matches were shams. They had to be genuinely tough guys with actual wrestling skills, Schire says, so they were able to protect themselves.

Promoters owning territories

By the 1920s, wrestling was becoming more professionalized, moving away from the traveling carnivals and barnstorming circuits into a more locally based system made up of small independent owners all across the country known as promoters.

“Each of them had their own individual towns,” Teal says.

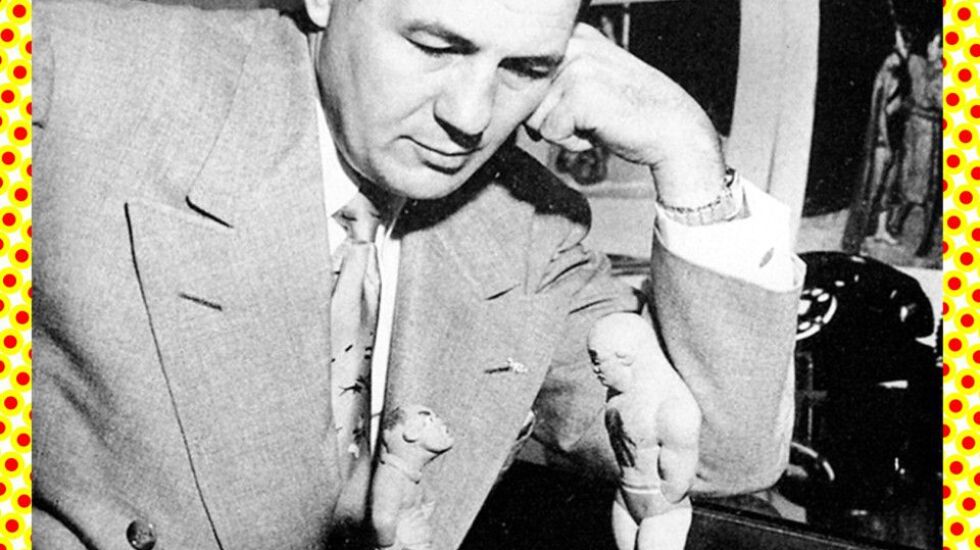

These promoters were people like Fred Kohler, a stocky guy out of Chicago. Kohler was born Fred Koch and started out as a wrestler. Kohler was known for his imagination as a promoter. He had an outsized impact on Chicago and its golden age of wrestling.

By the early 1930s, some promoters were making serious cash. And it could get cutthroat. Teal says bigger promoters would move in on smaller promoters’ areas.

Soon, big promoters like Kohler could develop a homebase: a circuit of cities and towns, then regions, eventually an entire territory.

By the 1940s, there were dozens of independent wrestling territories across the country with different rules, different wrestlers and different title-holders.

After World War II, some of the most powerful promoters banded together to become the National Wrestling Alliance. The NWA was about as close as pro wrestling would ever come to a national league model with a centralized body making all of the rules.

This move wasn’t necessarily about improving the sport. Richard Vicek, author of “Bruiser: The World’s Most Dangerous Wrestler,” says the NWA was “a monopoly-like umbrella organization for professional wrestling.”

“By working together, they would maximize all their profits, all their hold,“ says current NWA owner William Corgan, “and they would be able to shut out anybody else making a challenge to them on any kind of local or regional level.”

It was a racket. And, in 1949, Kohler and his Chicago operation joined its ranks at just the right moment.

TV makes Chicago king of the ring

Kohler had started his operation in his father’s bar, but he was now booking shows in premier venues in Chicago. He had top wrestlers under contract and the Illinois State Athletic Commission — the governing body forl pro sports in Illinois — in his pocket, according to the book “National Wrestling Alliance: The Untold Story of the Monopoly that Strangled Professional Wrestling” by Tim Hornbaker.

He was now running pro wrestling in Chicago and in 1946 he brought the sport to television with a show called “Wrestling From Rainbo.” It was a huge hit.

On wrestling nights, neighbors would gather at the home of the family with a TV to watch. Stores downtown put TVs in the windows so people could watch.

Kohler’s show, with its flashy maneuvers and athletic moves, was an early version of today’s pro wrestling.

At first, some promoters worried televised wrestling would eat into box-office sales. But it had the opposite effect. In time, Kohler was putting on a second local, weekly show, then a third.

The TV shows were cheap and easy to produce, says former wrestling promoter Bob Brooks, with one camera getting the width of the ring and the other a closeup view.

But wrestling was still a local business, airing on local TV. It needed something bigger.

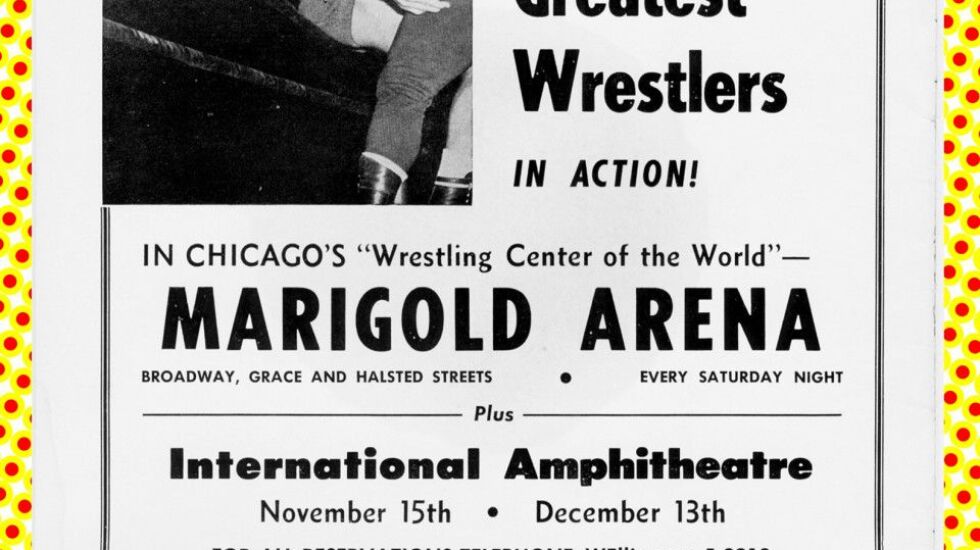

In 1949, Kohler brought his new TV wrestling show into living rooms across America through a contract with the budding DuMont Television Network, which had a semi-national reach. Kohler called the show “Wrestling from Marigold,” and it aired in Chicago on WGN.

Chicago’s golden age of wrestling

“Chicago was it during those years,” Vicek says. “Fred Kohler called the shots … He decided which wrestlers were going to get the big promotion. Who’s going to win or lose, who’s going to be brought in, who’s going to be sent walking.”

Into the early 1950s, Kohler was on top of the wrestling world, bringing attention and top wrestlers to Chicago.

Kohler knew he had to bring his TV audience drama and dash in bigger doses. What better way than to return to wrestling’s earlier days, featuring matches between heroes and villains — in wrestling parlance, “babyfaces” and “heels.”

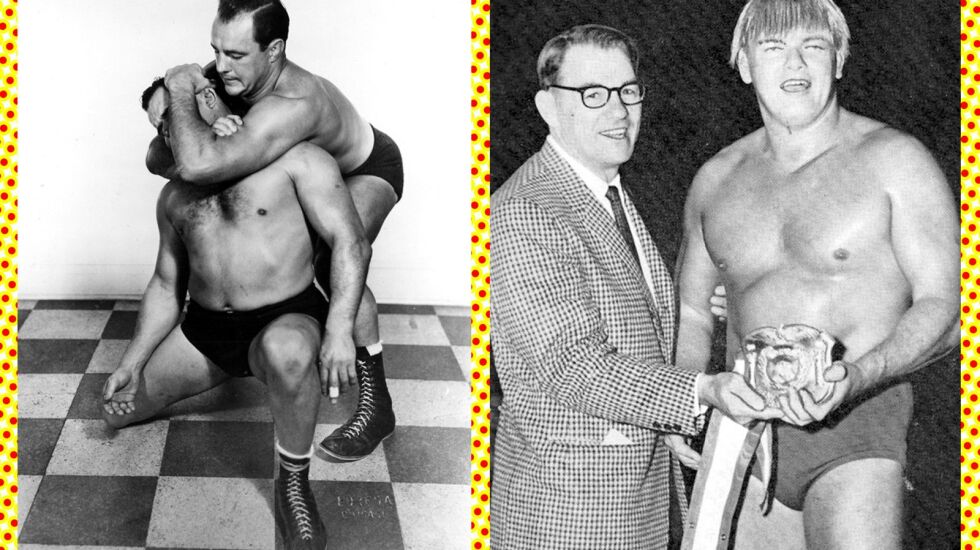

One of the early babyfaces Kohler brought to a national audience was Verne Gagne. According to his son Greg Gagne, he had a childhood dream to be a wrestler and also played football. He was drafted by the Bears but let go by team owner George Halas.

Kohler recruited Gagne to wrestle. But Greg Gagne says his father refused to do some of the wild things Kohler wanted him to do, like dress as a martian and be lowered from the ceiling to the ring: “He told him, ‘No. … I want to go down to the ring, and you can bring these guys in — everybody here in the locker room. I’ll wrestle them one at a time, two at a time, three at a time. And, if I can’t beat them all, I’ll quit.’ ”

No one would get in the ring with him.

Gagne’s physique and genuine wrestling talent helped him win over audiences. And Kohler’s national reach helped make Gagne a star.

But for wrestling to continue as a morality play with heroes and villains, the babyfaces needed some heels: wrestlers like Bill Afflis, aka Dick the Bruiser.

The headline from a 1955 article in Wrestling Life, which Kohler published, said of him: “The Romans had their great gladiators… Medieval history had its mighty torturers… and we have The Bruiser.”

The Bruiser was a hulking brickhouse of a man barreling down on his opponent, ignoring the rules and clobbering his foes.

With a “voice like a ruptured foghorn” and a temperament to match, Dick the Bruiser was foreboding. Fans loved to hate him, Vicek wrote.

Chicago golden age’s end

Kohler seemed unstoppable, and so did Chicago’s golden age of wrestling — until the winter of 1955, when the DuMont network, embroiled in financial crises, canceled “Wrestling from Marigold.”

Without the show, Kohler’s bread-and-butter was largely gone, along with his influence over pro wrestling.

Then, in the spring of 1957, WGN also cut ties with Kohler.

As his business was going down, so was Chicago’s influence in wrestling.

But what Kohler created during that golden age of professional wrestling — bawdy matches, over-the-top theatrics, heroes versus villains — is still the stuff of wrestling theater today.