Designer belts, footwear, accessories and jewellery fade into insignificance in the glitter of exhibits at the Amrapali Museum in Jaipur. Silver and gold mojris worn by a young royal from Patna, an intricately worked silver belt from Kerala for keeping coins, two-kilogram silver anklets from Bhuj and ruby-studded back scratchers are just some of the 4,000 exhibits that dazzle visitors.

In the 1980s, Rajiv Arora and Rajesh Ajmera, students of history and businessmen in handicrafts and silver from Jaipur, used to travel extensively for business. On a trip to Kekri, 90 kilometres from Ajmer, Rajasthan, Rajiv met a villager with a rich collection of silver jewellery. Rajiv takes up the narrative, “One piece he had was a beautifully made silver bugle with the image of Hanuman and an engraving that said that the sound of the bugle could be heard 40 kilometres away. It was an instrument to alert soldiers when a region was at war. I was in my 20s when I bought that.” But he adds that for every such find, there were instances when he travelled for hours in vain. “For us, every piece in our collection is precious because we have travelled the length and breadth of India to buy them. So, a silver toe ring as such may not be expensive but if it completes a collection of a period or a community, then it is invaluable for us,” says Rajiv.

Over the years they found vintage pieces from far-flung villages and tribal communities that were so beautiful, they did not have the heart to sell or melt them. Hence, their collection of exquisite pieces kept increasing.

In January 2018, they decided to share this treasure trove of workmanship and history with the public by opening the Amrapali Museum in Jaipur. Dedicated to Indian jewellery, especially silver, today it is the only one of its kind.

It was the same desire to conserve cultural moorings that motivated Deborah Thiagarajan to establish the Madras Craft Foundation in 1984. In 1991, the Foundation received 10 acres on a long lease from the State government of Tamil Nadu and set up the DakshinaChitra Museum on the ECR Road. Today, the vibrant space houses 18 heritage homes from South India, offering a vivid snapshot of life into their communities and regions.

Meanwhile, in Mumbai, entrepreneur and industrialist Samir Somaiya, Chancellor of Somaiya Vidyavihar, is working on opening an institute for the fine arts, which will include a space to showcase his father Karamshiji Jethabhai Somaiya’s personal collection of precious manuscripts, sculptures, Pichwais, and paintings. Before the physical space of 50,000 square feet comes up, his personal collection has been digitalised and is open to art lovers at museum.somaiya.edu.

Samir explains: “We are setting up an institute for the fine arts and I want students who enrol there to have a first-hand experience of seeing the art works instead of merely reading about them or seeing pictures. They can see for themselves the styles, brushwork and colour palettes.”

Aditi Nayar Zachariahs, director of the Museum of Kerala History in Edappally, Ernakulam, inherited the space from her grandfather’s brother R Madhavan Nayar who founded the museum in 1984. She has turned it into a vibrant community hub with curated talks, exhibitions and shows.

In this age of private collectors who want to share their treasures and build communities around their collections, museums are built around an intriguing variety of objects. Sunny Mathew, for instance, is a passionate collector of records and he began the modest Discs and Machines – Sunny’s Gramaphone Museum and Records Archive, with his enviable collection of vintage vinyl, shellac records, gramophones and so on. Built beside his home on the banks of the Meenachil river in Pala, a town in the Kottayam district of Kerala, the museum is completely funded by Sunny: he is curator, owner and keeper here.

While private museums are not a new phenomenon in India, many more are in the pipeline now as collectors open up their vaults of precious art works, mementos and antiques to showcase them to the public.

Deepthi Sasidharan, independent curator and co-founder of Eka Archiving, has helped collectors curate and set up museums around the country. Explaining why more people are doing it, she says “In Independent India there have been individuals who went about building their life in dance, music, art, scholarship etc. The museums they have set up are a vibrant form of democracy and free will at work. As that generation passes on, they want to leave behind their life learning for the public, in the service of the community and society. That is the genesis and focus of all private museums.”

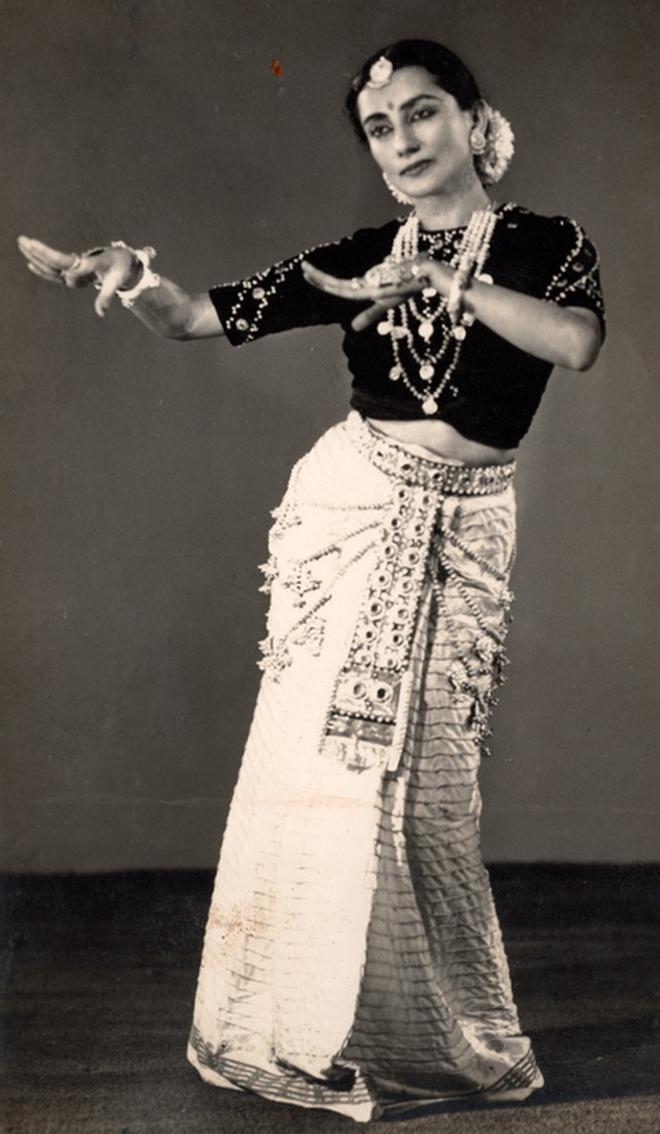

Deepthi’s previous work was the curation and setting up of the Dr. Savithadidi N Mehta Museum and the Viswa Gurjari Library in Porbandhar, Gujarat in 2022. This has a “fabulous collection of rare books, drawings of Manipuri dance movements and fine pieces of textiles.”

Preema John, director of the Bengaluru-based Indian Music Experience (IME), points out that in post-liberalisation era in the 1990s, many private museums were opened in different parts of the country. Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in Delhi (2010), Kasturbhai Lalbhai Museum in Ahmedabad (2017), The Partition Museum in Amritsar (2017) and Museum of Art and Photography in Bengaluru (2022) are some of the museums that opened during the last 20 years.

“The IME was set up in 2019 with a vision to fill a cultural gap in the country, and also to bring in a new narrative. We are unique because we are an institution built around a performing art (music) and the only one of its kind in India that is looking at the history and development of music in India,” says Preema.

Museums in the private sector are of different kinds, points out Preema. “While some are owned by one person or family, there are many established by trusts, corporates, and societies. In India many erstwhile royal families also have museums (such as the ones in Meherangarh, Thiruvananthapuram, Vadodara) that showcase lifestyles, culture, crafts and arts from another era. Some of the museums receive government support and funding,” she elaborates.

Challenges of setting up a museum

Pramod KG, independent curator and co-founder of Eka, elaborates on the challenges of setting up a museum. As a company, Eka has been in this highly specialised field for over 14 years and has curated exhibitions, set up museums and helped in archiving collections.

Getting a team to archive your collection, especially if you happen to live in a remote place, can be difficult. Young archivists are reluctant to come and live there. People with breadth of experience are needed to understand your collection.

To design a museum, one needs lighting designers, photographers, conservators, support staff … there is a whole team that is involved in setting up a museum. When collectors realise that there is a whole paraphernalia behind the setting up of a museum, some are reluctant to get involved.

If there is some ambiguity in the provenance of a piece in the collection, then some private collectors would not want to showcase it.

If the demands of opening a museum is Herculean, then the task of making it accessible and relevant is even more challenging.

Radhika Raje Gaekwad, managing trustee of the Maharaja Fatesingh Museum in Vadodara, says more than the day-to-day functioning of the museum, the challenge is to get footfalls into the museum and help build bridges between the community and the museum.

“We have a fabulous collection of Ravi Varma originals, European and Indian masters and rare artefacts at the Fatesingh Museum that is open to the public for a modest fee of ₹150. To visit the adjacent Laxmi Vilas palace costs four times more the price of the museum ticket but the rush is always to see the palace and not the gorgeous collection we have at the museum,” rues Radhika.

To build bridges between the community and the museum, activities are planned to help visitors understand the collections they showcase. For instance, Gita Hudson, curator of DakshinaChitra, says the crafts workshops, activities and curated walks organised at the museum see enthusiastic participants.

Emphasising on the significance of such spaces, Pramod KG, archivist and co-founder of Eka, explains that many exemplary pieces of Indian heritage have left the country but there is much that remains in our museums. “Without travelling abroad, we can see many of the treasures of Indian art and history right here in the country.”

As many of those working in museums point out, museum-going is not ingrained in most Indians. It is a Western concept that is only slowly gaining acceptance in India.

Preema says that building a “public imagination around the museum is necessary to make it accessible and relevant to the public.” She adds: “It has to be re-established, re-imagined all the time in the cultural landscape. It is an ongoing work if the institution has to remain significant for the patrons, community and audiences too.”

While private museums do need to be careful with expenditure, they have the ability to be flexible with timings, exhibitions and events since decisions will not be tangled in red tape.

The Raja Ravi Varma Heritage Foundation in Bengaluru, for instance, was able to coordinate and plan exhibitions and partner with other museums more efficiently than government museums in Kerala with extensive collections of Ravi Varma paintings.

Many of these museums also have cafés, artisanal studios and shops for visitors, which encourage promote divese activities such as print-making, tattooing, workshops, talks, curated exhibitions, and concerts. The idea is to change public perception of museums as intimidating and snooty by turning them into centres of infotainment. And, in the process, to connect with young audiences so they see these institutions as welcoming spaces to visit, learn from and find a community.

How do you value a collection, especially if it is an object that has become obsolete and has no relevance in the contemporary world beyond the realm of art and craft? Unlike visual art, where there is the hope of increase in value, how do you plan to weave stories around those objects?

Exhibitions, books, publications among others will help in deciding how accessible is the museum.