As they head to the polls to cast a ballot in primaries, voters may find themselves staring at a long list of candidates. In most cases, these primaries are winner-take-all. Whoever gets the most votes will represent their party in November.

There were seven candidates on the GOP primary ballot in New Jersey’s 7th Congressional District on June 7, 2022. Thomas Kean Jr. had 45.9% of the vote with 80% of ballots counted when the Associated Press declared him the winner. In Montana, five candidates competed in the June 7 GOP primary in the 1st Congressional District. With 78% of the ballots counted, Ryan Zinke was leading with 41.4% of votes and Al Olszewski had 40%.

There was a difference this year from primaries just a decade ago: Data from the Center for Election Science, a nonpartisan nonprofit focused on voting reform, indicates that in contested primaries, the number of candidates has been rising since 2010. That growth has important implications about the quality of the candidates and the views they represent.

Each additional candidate who gets votes lowers the number of votes needed to secure a nomination. The outcomes of primaries with many candidates are unpredictable and may result in extreme, inexperienced or controversial nominees who may not truly represent a majority of voters. And a fringe candidate winning the primary and advancing to the general election can mean a risky candidate for their party.

Flooded field

The average contested primary for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives grew from 5.2 candidates in 2010 to 7.3 candidates in 2020. This flooding of the field can be attributed to several factors, including the role of technology: Getting on the ballot is relatively easy, and candidates can promote themselves and solicit funds via social media.

As a political scientist in Missouri, I’ve been closely following this crowding of the field in our U.S. Senate race. Here, the GOP is reckoning with the presence of disgraced former governor Eric Greitens in a packed primary field of 21 candidates.

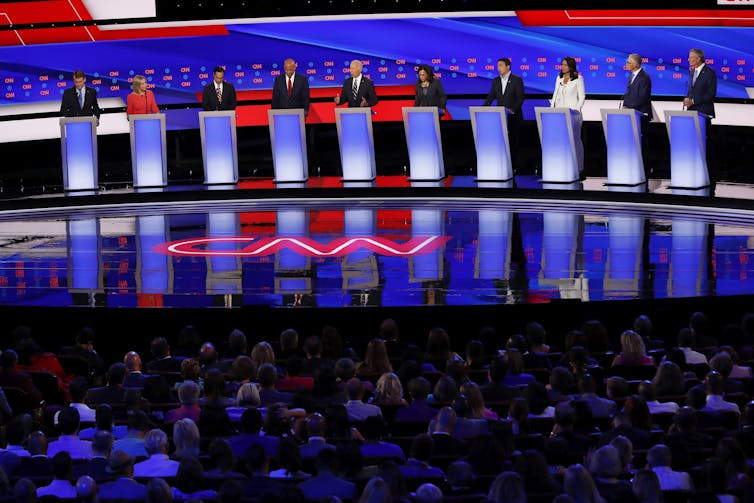

The crowding of fields is not limited to congressional candidates. The GOP presidential primary in 2016 featured 17 candidates, while the Democrats fielded 28 presidential candidates in 2020.

While the field began to clear for Joe Biden following February 2020’s South Carolina primary, eight months before the general election, Donald Trump won primaries well into March 2016 while hovering around 40% of the vote.

These crowded fields don’t always lead to the kind of results that prompt fear among party leaders of a general election disaster. For example, scandal-plagued Rep. Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina, who failed to get the support of mainstream Republicans in the primary race, was ousted after losing to a candidate who won 33.4% of the vote in an eight-person field.

Competitive versus safe seats

Being an ideologically extreme candidate can be an advantage in partisan primaries. Although there is some dispute in political science as to how representative party primary voters are of their parties, there is no debating that they are ideologically polarized subsets of the general electorate.

Candidate crowding in partisan primaries is more likely to happen in seats where the primary is the only true contest in the election. In these districts, it is a virtual certainty that one party’s nominee will win the general if they can survive the primary. Victorious primary candidates can often walk to a general election victory after winning a third or less of the primary vote.

This happened in Michigan’s 13th Congressional District in 2018.

Incumbent Rep. John Conyers had resigned. A primary election was being held for a Democrat to seek to finish out his term. At the same time, the Democratic candidate to run for a full term in Congress was also being elected.

Both races included Democrats Rashida Tlaib and Brenda Jones, among other candidates. Moderate Jones won the four-way race to compete for the remainder of Conyers’ term. Tlaib, currently a member of the left-wing “Squad,” won the six-way race to become the nominee for the full term. The presence of two additional candidates who were not close to winning had seemingly flipped the results.

National political party organizations may try to steer voters and clear the primary field in competitive districts, but candidates are often left to their own devices in safe seats. National and state parties would prefer to focus on competitive races than ones in which their side will likely win regardless of the nominee.

Where ideological extremists run in competitive districts and win the primary, it can present a different problem. The extremist’s party can be damaged by their candidacy with a lower vote share in the general election.

‘Extreme, inexperienced or controversial’

Several primaries in recent memory have followed the pattern of elevating extreme, inexperienced or controversial primary candidates into party nominees.

In the special election Democratic primary for Florida’s safely Democratic 20th congressional district in November 2021, Sheila Cherfilus-McCormick won by just five votes. Cherfilus-McCormick, who had never held elected office before, won 23.8% of the vote in a field with 10 other candidates after spending millions of her own money on the campaign. She won the general election.

This year, in the GOP House primary in Ohio’s 9th congressional district, J.R. Majewski won with 35.8% of the vote. Majewski, a proponent of the QAnon conspiracy theory who has never held political office, defeated two state legislators in the primary.

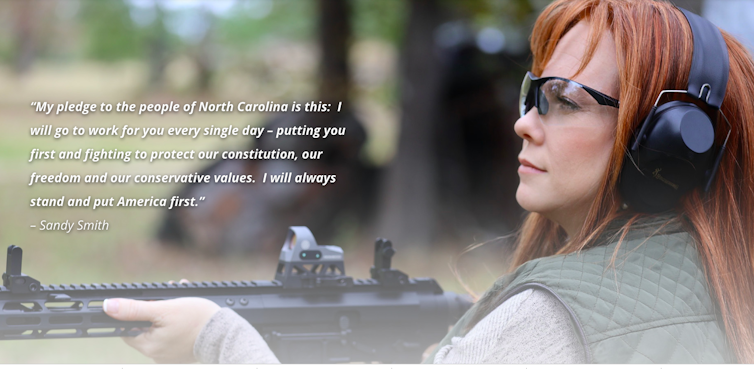

In the GOP House primary in North Carolina’s 1st congressional district, election conspiracy theorist Sandy Smith won the primary with 31.4% of the vote, defeating seven other candidates. One of her GOP competitors dug up allegations of abuse against Smith by multiple ex-husbands and her daughter. She has denied them.

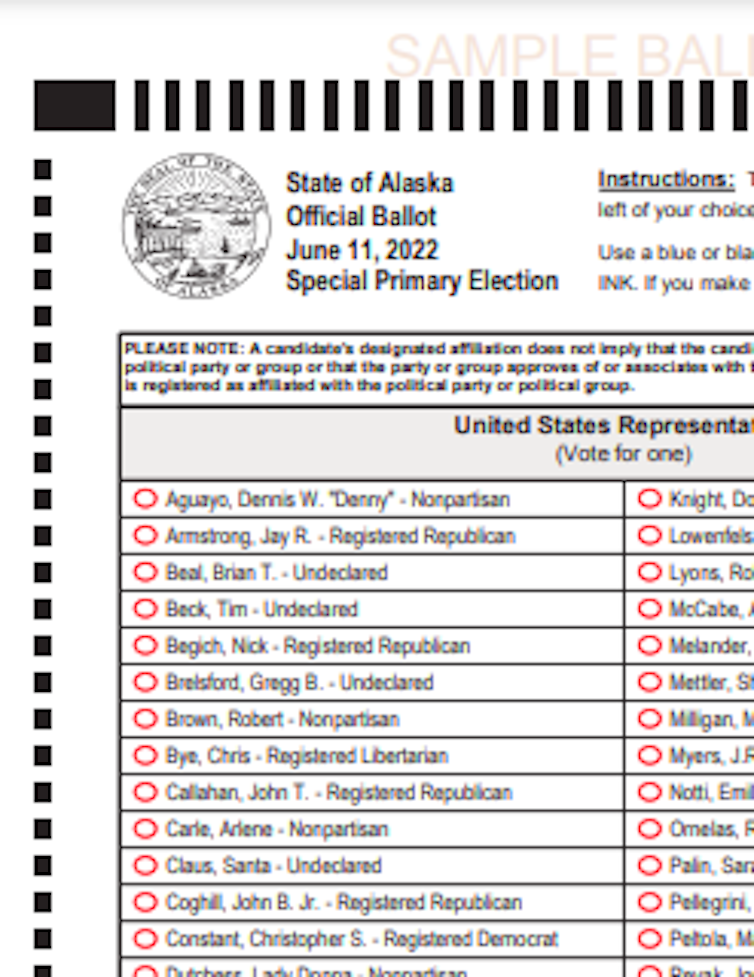

In perhaps the most extreme example of a crowded primary field, the nonpartisan special primary election to replace Rep. Don Young in Alaska asks voters to wade through 48 candidates, ranging from Sarah Palin to Santa Claus. Yes, Santa Claus. While ranked-choice voting in the general election might lead to a consensus choice, the wide-open primary has led to questions from voters about how to ensure they’ll have one of their top choices make it to that stage.

‘Nothing approaching a majority’

While the quality of a candidate is in the eye of the beholder to some extent, the pattern here is political newcomers, often with strong ideological views, winning their parties’ nominations with nothing approaching a majority.

On one hand, contested primaries can be symbolic of a vibrant democracy. They can indicate that candidates want to get involved and are able to do so. They offer multiple perspectives for voters.

On the other hand, these crowded fields can make choosing more difficult for voters. They have to make decisions with little knowledge of how other like-minded voters will vote. Strategic support for a specific candidate can be hard to coordinate.

With votes split among multiple candidates, a candidate may win with a small plurality while being disliked by, or disconnected from, the larger primary electorate.

Runoff elections that exist in many Southern primaries and ranked-choice voting in Maine can help in requiring candidates to meet a certain threshold of support. In the majority of states, however, 2022 will provide, I believe, countless examples in which primaries are akin to what political scientist Henry E. Brady described as “poorly designed lotteries.” With lots of candidates on the ballot, the winners of those lotteries may not be the voters.

Matt Harris does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.