Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is proposing a form of price caps on basic food items like milk and bread to slow their price increases. This is likely to set maximum prices which sellers are not allowed to exceed, though it appears it would be voluntary.

Price caps are loved by the public: 71% of UK voters supported them in a 2022 poll. But they are equally hated by economists: 75% oppose price caps even in emergency situations, according to another 2022 poll. Why is there such a divide? What are the downsides of price caps?

The UK government is reportedly considering a plan akin to what France did in the spring, where supermarkets were invited to voluntarily freeze or cut prices on selected items to the lowest level possible.

A concern is that voluntary price caps won’t do much. And the danger with introducing price caps below current levels is that some suppliers are likely to drop out of the market and stop supplying. That’s because the capped prices no longer cover their costs. Thus, food price caps could lead to empty supermarket shelves.

There are multiple examples from other countries where price caps have led to shortages:

Zimbabwe ordered price caps on basic goods such as groceries to fight hyperinflation in 2007. The resulting empty supermarket shelves forced shoppers to get in line at 5am to get the bare necessities before stocks ran out.

Hungary capped the price of petrol in 2020. As international oil prices surged after the Ukraine invasion, suppliers could no longer cover their costs. Imports to Hungary dried up, leading to a petrol shortage. Hungary was forced to abandon the price caps to restore supply.

After Berlin capped rents on properties in 2020, the number of flats on the rental market decreased dramatically. San Francisco had a similar experience in the early 1990s.

Alternatives

So what else could be done to bring food prices down? Representatives of the UK supermarkets argue that instead of capping prices, the government should reduce bureaucratic requirements for the industry such as border checks. But can less paperwork really reduce prices?

A London School of Economics study estimates that tougher Brexit border controls since January 2021 increased food prices by 6%. This number does not account for the entire food price increase of 19% within the last year.

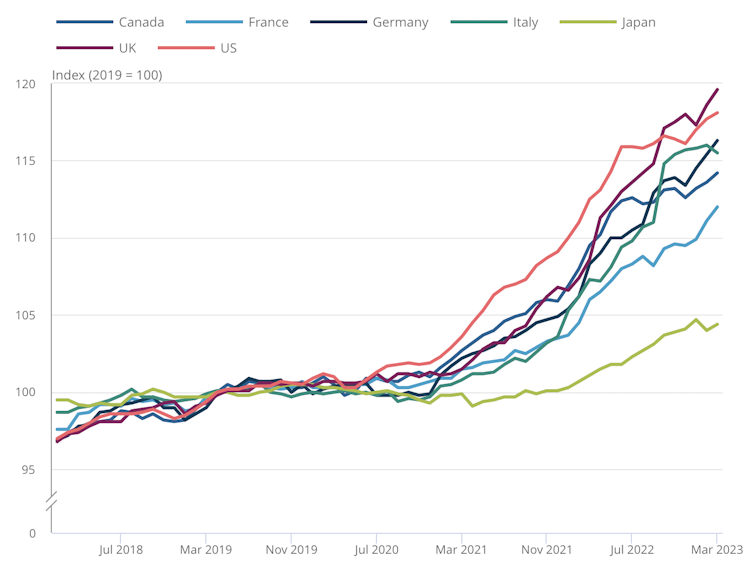

Nonetheless, this part of the price increases is a choice. With or without Brexit, the UK could have avoided this problem by having a more liberal border policy, but it didn’t. The EU has erected similar trade barriers against the UK, but the UK is being hit harder because it relies on the EU more for imports than the other way around. This partly explains why UK inflation is the highest among G7 countries.

Consumer price inflation across the G7

EU import border controls are also scheduled to get even tougher by the end of 2023. If an Italian supplier exports Parma ham to a German supermarket, there are no forms to fill at the border. If the Italian supplier exports that same ham to a British supermarket, they will have to pay a veterinary doctor to fill out forms declaring the meat to be safe, get those forms checked at the border, pay inspection charges and so on.

More EU suppliers are then likely to stop UK deliveries, or increase prices to offset the additional compliance costs. UK food prices would then rise further, which the government could avoid by loosening its own border checks.

Of course, red tape extends beyond border checks and imports. By reducing other regulations such as the ever increasing financial reporting requirements imposed on UK companies, the government could help reduce prices at least a bit. Every additional lawyer, accountant or administrator adds to food prices – without putting more items on supermarket shelves.

What would a doctor do?

An unconscious patient comes into A&E with a high temperature. “Ah,” says the novice doctor who is holding the fort, “we need to bring the temperature down”. He orders an ice bath. An hour later, the patient is dead. Focusing on the symptom, the underlying cause (perhaps an infection?) was left untreated.

The analogy of temperature and prices is crude but apt. Like a good doctor, economists distinguish symptoms from causes. Border controls are one cause of high food prices; others include higher energy costs and too few workers for the food industry.

It would therefore help if the government let fruit pickers in from abroad and encouraged inactive British workers back into the workplace. It could also speed up planning procedures for wind and solar energy generation to bring electricity prices for greenhouses down, albeit the benefits would take a while to feed through.

Together with loosening border checks for imports, this would be a more effective response than price caps. Merely focusing on the symptoms is not the way to get the patient on the road to recovery.

Christoph Siemroth receives funding from the UK Economic and Social Research Council, grant number ES/T006048/1 and ES/T015357/1.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.