Jane Carey’s new book Taking to the Field explores a paradox: women have been excluded from Australian science for many social and political reasons, but were also present and active within it from its earliest days. It’s a story of extraordinary achievements as well as struggles to gain recognition and fair treatment.

Review: Taking to the Field: a History of Australian Women in Science - Jane Carey (Monash University Publishing)

An array of fascinating and talented characters populates the book. One of the most controversial is Georgina King (1845-1932). Among her many other investigations, she questioned the accepted wisdom that human evolution was driven by men. In 1902, she retold the narrative with women at the centre, arguing they were first to walk upright and develop language.

It was a powerful challenge to the prevailing idea that women “were inferior because they were less evolved”. Her vision was before its time: it wasn’t until the 1990s that feminist archaeologists and other scholars took up the baton to argue for women as equal creators of human culture.

King’s work was plagiarised, and she was not fairly credited for what she had achieved. The more she objected, the more she was painted as unhinged and mad. It’s a familiar story even today.

Read more: Women still find it tough to reach the top in science

Science and empire

Carey provides a nuanced analysis of how early Australian science was entangled with social Darwinism, eugenics and genocide. She embeds the practices of collecting specimens and artefacts for scientific purposes in a nexus of colonial mastery and frontier violence. Importantly, she also notes the contributions made by Indigenous people, including women, in providing expert botanical, zoological, geological and other knowledge.

A history of science might not usually include social activism. Carey describes how women were the backbone of science-informed social reform movements in the late 1800s and early 20th century.

Women were supposed to stay out of politics and concern themselves with the domestic sphere, but social reform was an acceptable arena for white, middle class women to exercise their talents. Their efforts established kindergartens, school medical services, sex education and family planning clinics across Australia. However, as Carey points out, these lofty ideals were also often driven by racist and eugenic motivations.

The emphasis on mothers and children’s welfare had a sinister and very political side. It was mobilised to support empire and “White Australia”. Improving the lot of whites would keep at bay the rising tide of “degenerates” and the threat of miscegenation or “race-mixing”.

Australian women and women’s organisations participated in global networks promoting eugenics. The goal of keeping the race “pure” led directly to the Stolen Generations and other atrocities.

Victim or pick-me girl?

From the late 1800s, female scientists were herded into lower roles such as laboratory demonstrators, and paid less than their male counterparts for the same work. They were expected or forced to resign upon marriage.

A “marriage bar” for Commonwealth employees lasted until 1966 (and informally long after that). It’s worth reflecting on what marriage entailed for women before the rise of second-wave feminism. It meant, in general, that a woman was financially dependent on her husband. She was obliged to relinquish her identity as an adult human being to serve the needs of her husband and children.

Women lost not only their surname but their first name too: they became “Mrs Joe Bloggs”. They lost their bodily autonomy, being expected to provide sexual services to their husband. Rape in marriage was legal until 1976 in South Australia and later in other states. (At high school in the early 1980s, I was taught that it was a sin to deny a husband his conjugal rights).

For those not forced out by marriage, cracking the glass ceiling was often impossible. The case of Ethel McLennan’s rejection for the post of professor of botany at Melbourne University in 1937 highlights a problem that is every bit as prevalent today. The man chosen instead of her was, to quote one of her colleagues, appointed “on his promise rather than his established position”.

Despite such practices, many academic women in the 1930s and 40s were adamant that they had experienced no discrimination. Carey points to a 1941 survey, which suggests that university women had a “far lower perception of discrimination than those employed elsewhere”.

Carey notes that, at a time when universities were elite and expensive institutions to attend, these women were already very privileged compared to the bulk of their sisters. Over time, pay parity had increased, and many women continued to work after marriage. But they were sequestered in poorly-paid, low-ranked jobs, and in fields, such as botany, which had few men.

Many, from the 1940s to the 1970s, explicitly rejected feminism, while also working to achieve social goods around education and health. Carey unpicks this contradiction. She quotes botanist Margaret Blackwood from 1980: “I am not a feminist or women’s libber … I do get stinking mad when I see prejudice against women, but it’s no good having a chip on your shoulder. You don’t get anywhere”.

Georgina King was evidence of that. But the choice was between being the victim or a pick-me girl, in today’s parlance. Neither is a winning position for women.

The blokes take over

In the decades after the second world war, Australian science became the field of men. The contribution of science to the war efforts increased its prestige; and although the numbers of women studying and gaining employment after the 1940s remained steady, they were now vastly outnumbered. Carey argues that numerous changes in this period led to the shape of science professions as we see them today.

Because of the marriage bar, promoting science careers to women was seen as a waste of time. In any case, job advertisements specified if they were for men or women; and until the 1970s, most of them were for men.

It was particularly difficult to get research positions, which, as Carey points out, made it hard for women to define themselves as scientists as they were not able to conduct research. As usual, teaching science was more accessible than being a scientist.

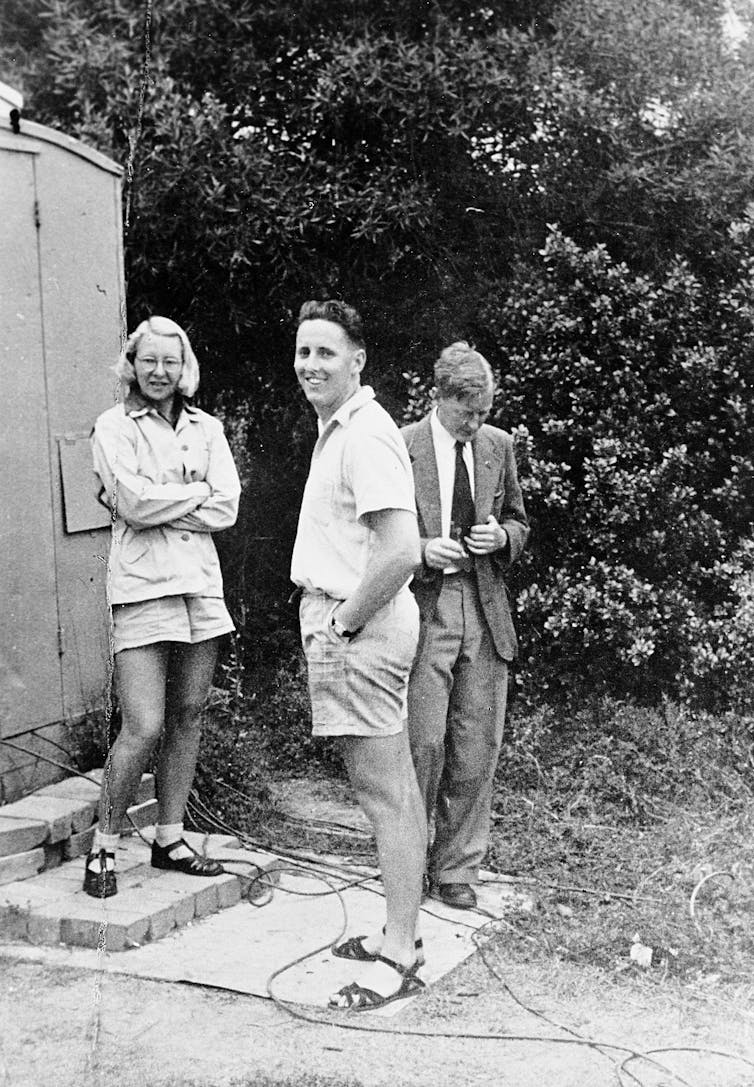

The radioastronomer Ruby Payne-Scott noted in the 1940s:

There is probably more prejudice against employing women in mathematics and physics than in any other science except geology.

Payne-Scott’s research is foundational to the entire field of radioastronomy globally. When I first became aware of her work, her contributions as represented in Wikipedia were trivialised and underplayed in favour of her male collaborators. That has thankfully changed. Now she is celebrated by her former employer, CSIRO; but she was one of many forced out of science by marriage.

Women dominated in fields like biology, botany and dietetics, which are still considered more appropriate for women than the “harder” sciences of physics, mathematics and engineering.

Carey documents how this division was predetermined by school subjects. Girls’ schools did not teach physics, while boys’ schools did not teach biology. In the 1940s and 1950s, this led to the numbers of women taking chemistry and physics in Victoria dropping radically.

In the universities, women were edged out of the positions they did hold even in the female-dominated fields, with some male professors actively trying to replace them with men.

By the 1950s, Carey says, the current gender divisions with women in the “soft” sciences and men in the “hard” sciences were entrenched. The post-war marriage boom further alienated women from science careers. If anything, the 1940s and 50s were more sexist than the pre-war decades.

There was a shortage of scientists; but anything was better than employing a woman. Men were preferentially appointed over more qualified women. Many senior scientists and science administrators began their careers in these decades; and these are the attitudes they were inculcated with.

Women also experienced discrimination because they had two jobs, as wives and mothers, and as employees. Their lower capacity to work at all hours was a black mark against them. Hence men derived the benefit of having their career supported by their partner’s domestic and emotional labour, and an absence of female competitors at work.

Women were (and still are) competing against this unfair advantage. It was not a social expectation that men shared domestic and family duties equally with women until the 1980s (and the current expectation that they do is very different from reality). This was no meritocracy or level playing field.

As Carey says of the post-war decades,

The fact that women were excluded so strongly, even in the face of the severe shortage of qualified scientific workers, is suggestive of the importance of masculinisation to the status and self-image of science in this period.

As the face of science in Australia changed, the professions started to forget the earlier achievements of women in the field.

The lack of toilets

“The field” refers to a disciplinary area, but it also means the location of fieldwork – outside the laboratory, often in remote or difficult places, where scientists go to collect data.

Going into the field for women was a radical act. They were supposed to stay at home, or at most, in the lab or classroom. Their participation was also restricted by the lack of toilets – in Victorian Britain, this was called the “urinary leash”, which limited the distances women could travel. Lack of toilets was used as an excuse for why women could not be employed, or work at field research stations.

In the 1950s, a woman who responded to a survey by Carey related how

After rejection of several job applications with the excuse of ‘no toilets for women’ at our research station, I decided to study nutrition and dietetics, a predominantly female field.

Many women were rejected for jobs because they were not held capable of fieldwork. As a young archaeologist, I heard these stories from more than one senior woman. This was even before factoring menstruation, pregnancy, lactation, and menopause into managing fieldwork, and without raising the constant threats of sexual harassment and violence.

Read more: How to keep more women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM)

Fieldwork is a radical act

Only in the last decade has it become possible to discuss these issues. Being in the field entails risks for women scientists because of the behaviour of men. There’s no getting around this.

Inevitably, reading a book like Taking to the Field invites us to contemplate how much has changed and how much remains to be done. As Carey says, there is power in “naming and claiming” forgotten women scientists. So many were relegated to work perceived as routine and repetitive, such as demonstrating, teaching, cataloguing stars, or programming computers.

Re-categorising these skills and knowledge enables their substantive scientific contributions to be recognised, as audiences have seen so compellingly in films like Hidden Figures. Making these women visible again isn’t just about having more role models: it’s about feeling that science is a place where we belong.

Once again, there is a shortage of scientists, while the number of women in STEM fields has barely increased over recent decades. The reasons are complex; but they can’t be addressed without understanding the deeper context provided by Carey’s invaluable analysis of Australian science.

Alice Gorman is a member of the Women in Space Chapter of the National Space Society of Australia. She is a former mentor in the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs Space4Women programme.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.