Having a baby permanently changes the make-up of a woman’s bones, a new study suggests.

A team of anthropologists discovered that female primates who have given birth have lower levels of calcium and phosphorus than those who have not reproduced.

Their bones also experienced a significant drop in magnesium as a result of breastfeeding.

However, while other studies show that a loss of calcium and phosphorus could lead to weaker bones, these new findings do not look at the health implications of the decrease of these minerals.

Instead, the work illuminates how dynamic bones are, changing and evolving with life events.

Dr Shara Bailey, an anthropologist at New York University, and co-author of the study, said: “A bone is not a static and dead portion of the skeleton.

“It continuously adjusts and responds to physiological processes.”

It has been long established that menopause can have an effect on women’s bones but the effect of giving birth is less researched.

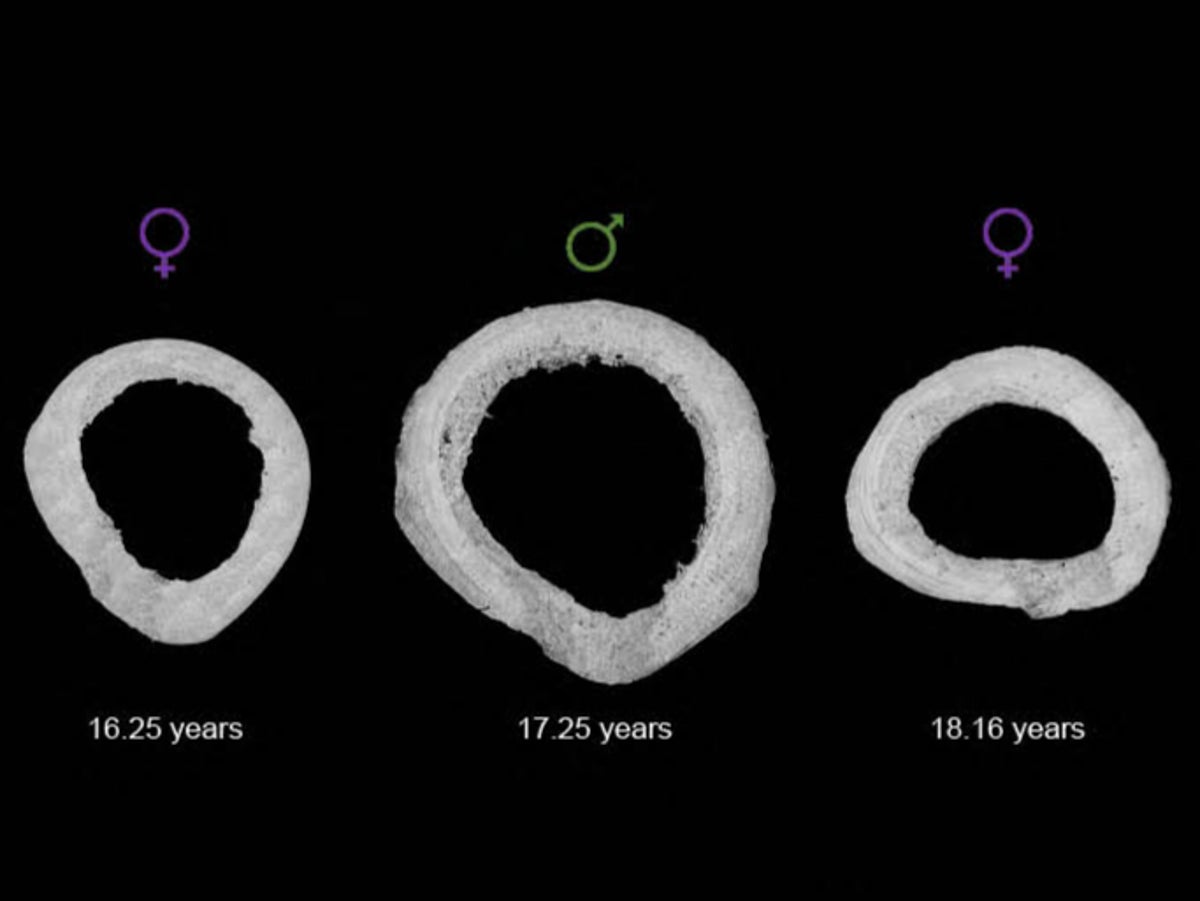

To gather these results, researchers studied the growth rate of the lamellar bone in the thigh of both male and female primates.

The lamellar bone is the main type of bone in an adult skeleton and is ideal for this type of investigation, as it evolves over time and leaves biological markers of these changes.

Dr Paola Cerrito, a doctoral student in New York University’s department of anthropology and college of dentistry, and research leader, said: “Our findings provide additional evidence of the profound impact that reproduction has on the female organism, further demonstrating that the skeleton is not a static organ, but a dynamic one that changes with life events.”

To study these bones, researchers used electron microscopy and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis to look at the chemical composition of tissue samples from the bones.

This method allowed scientists to work out the changes in levels of calcium, phosphorus, oxygen, magnesium, and sodium.

The primates they studied lived in Sabana Seca Field Station in Puerto Rico and died of natural causes.

Dr Cerrito said: “Our research shows that even before the cessation of fertility the skeleton responds dynamically to changes in reproductive status.

“Moreover, these findings reaffirm the significant impact giving birth has on a female organism — quite simply, evidence of reproduction is ‘written in the bones’ for life.”

The study was published in the journal PLOS ONE.

SWNS