Although it may sound like a legal maneuver, contrapuntal motion is actually a term used to describe how two musical parts interact.

Think about the relationship between a melody and a bassline, for example, in terms of the directions they’re travelling up and down the scale.

If you have a melody with notes that are moving up the scale, getting higher in pitch, it’s known as ‘upward motion’, whereas if it’s moving down the scale it’s a ‘downward motion’.

Straightforward so far, but it’s when you combine two parts and start to experiment with their motion relative to each other that things start to get interesting.

When you have two parts that work together, like a bassline and a melody, this is known as counterpoint. So, when dealing with the direction in which each part moves relative to the other, the general term for this is contrapuntal motion, and it comes in four different flavours: oblique, parallel, similar and contrary.

So how is this relevant to modern music production? Well, by altering the relationship between the bass part and the melody, you can produce profound effects capable of injecting tension and movement into a broad spectrum of musical genres.

The four types of motion mentioned above are mainly considered when employing a composition technique known as voice leading, which is a whole other story/lesson. For now, we’ll be briefly illustrating an example of each type of motion just so we get the basic idea, rounding off with a look at contrary motion and how it can be used in your tunes.

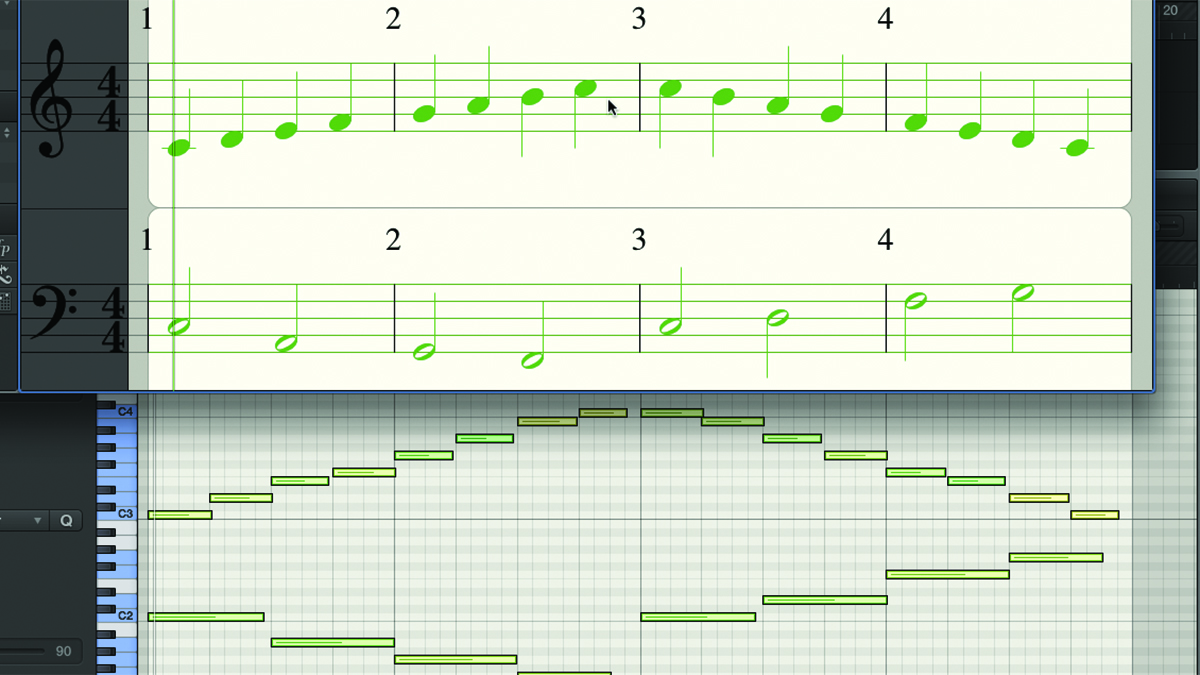

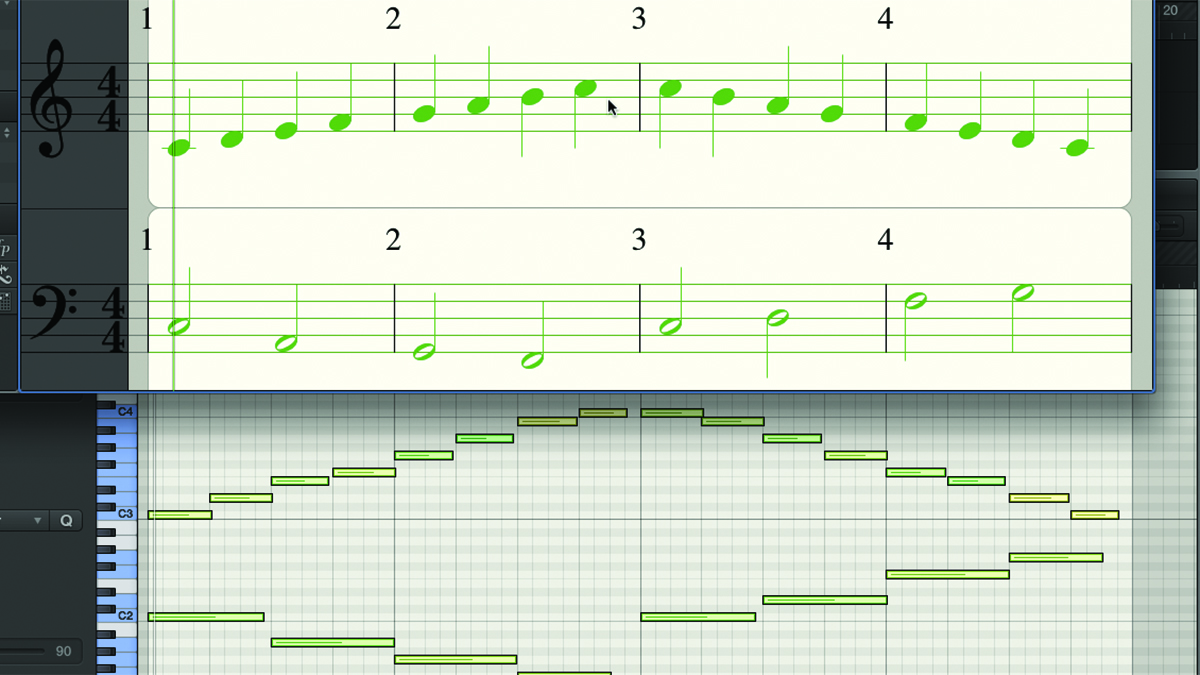

Step 1: Oblique motion is when one part moves up or down in pitch while the other remains constant. In this example, we have a melody that ascends and descends the scale of A minor, while the bass part maintains a steady A note. This is quite a common technique in electronic music, as it’s fairly easy to make a melody work over a static bassline.

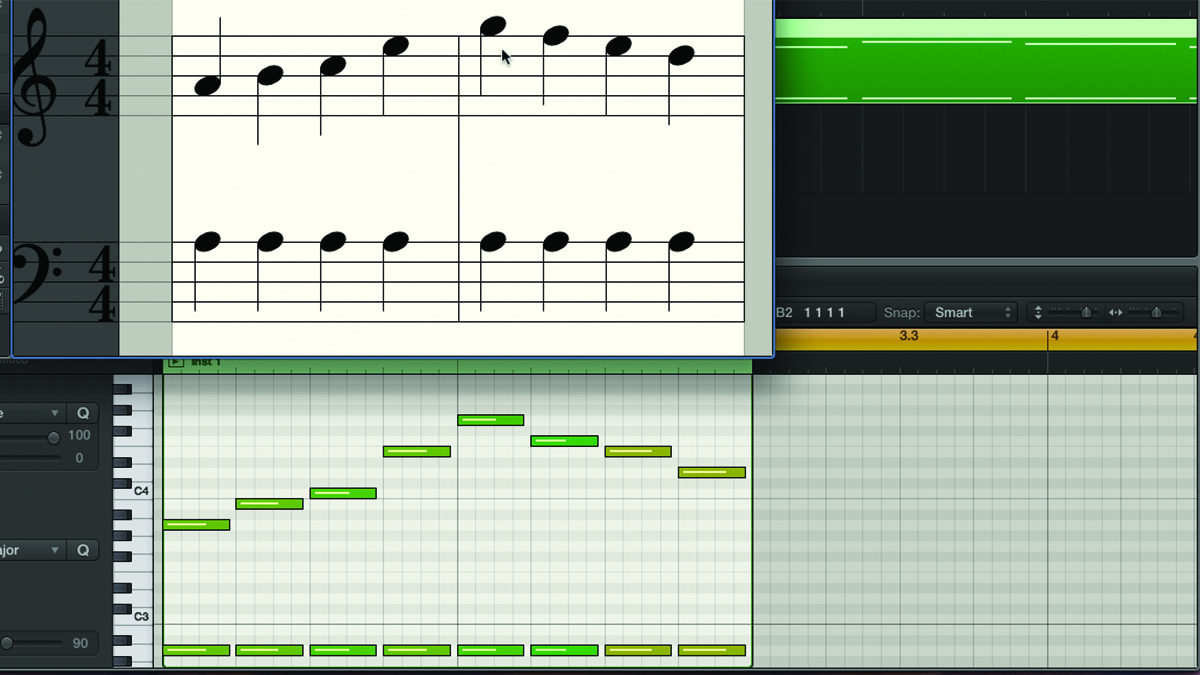

Step 2: Parallel motion is when two parts move the same number of semitones simultaneously in the same direction. If one part moves up a semitone, the other must follow suit, but because they always maintain a constant interval, like a synth playing two oscillators tuned semitones apart, parallel motion parts rarely harmonise properly in the current key…

Step 3: Because each pair of notes is always a fixed number of semitones apart, they often hit notes that aren’t in the right scale for the key. It would be better if you could adjust the interval between the notes when needed so that each pair of notes harmonised properly with its partner, and the key of the piece. This is where similar motion comes in…

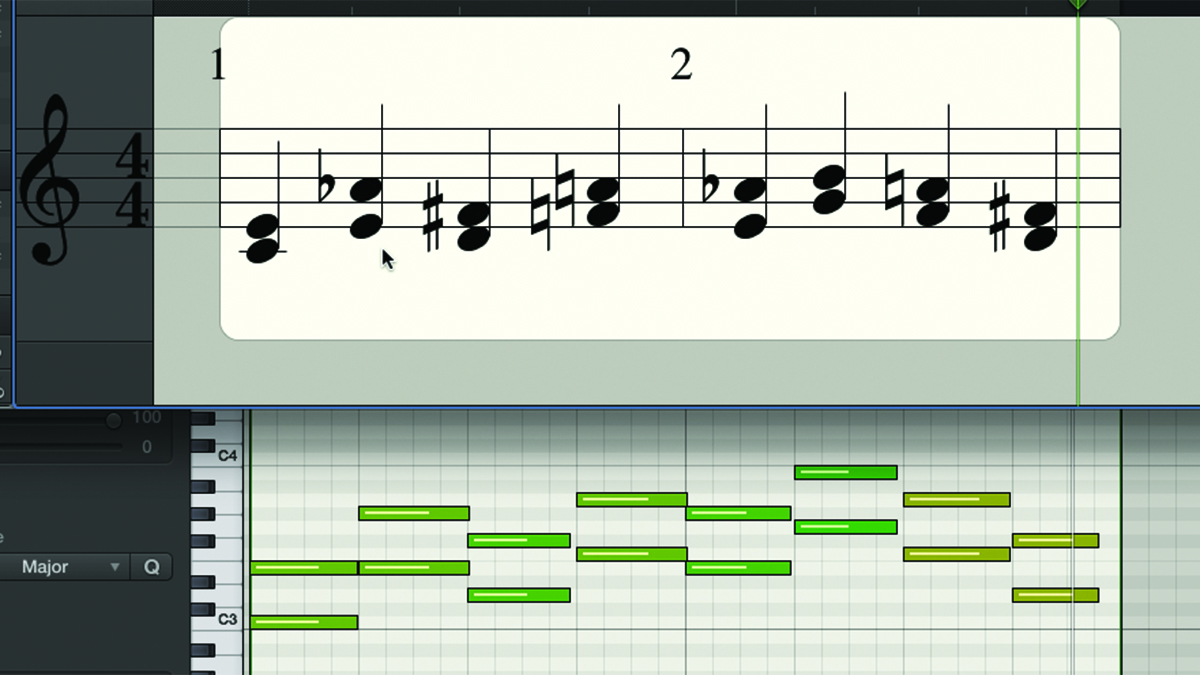

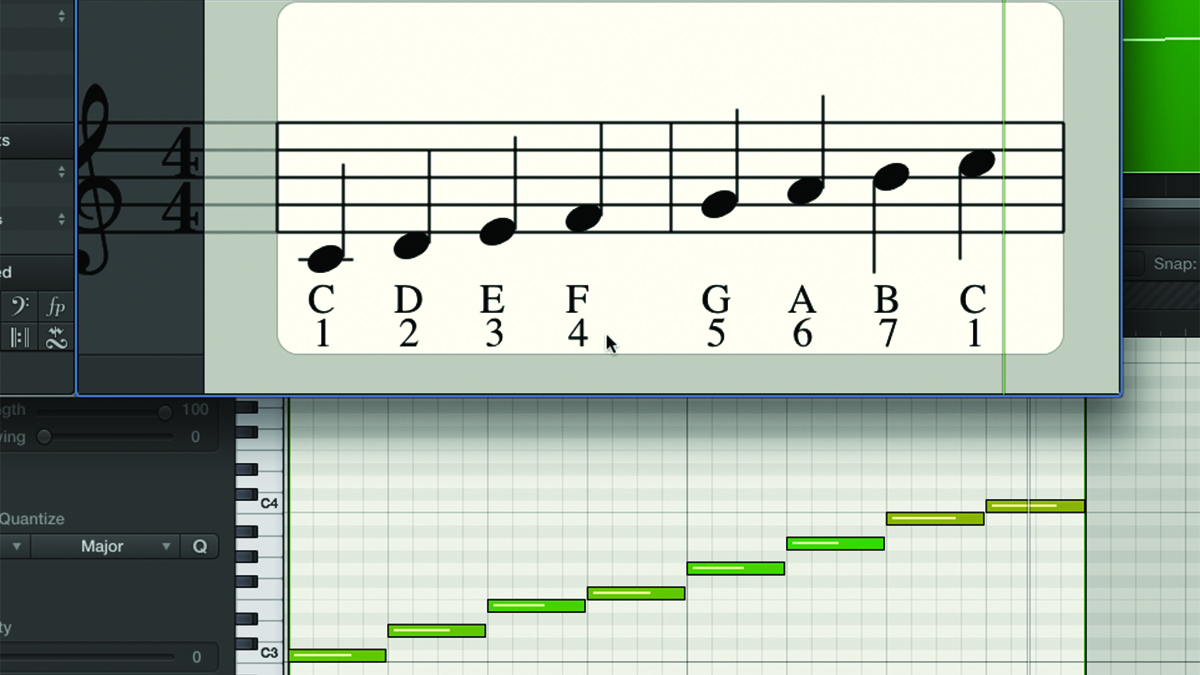

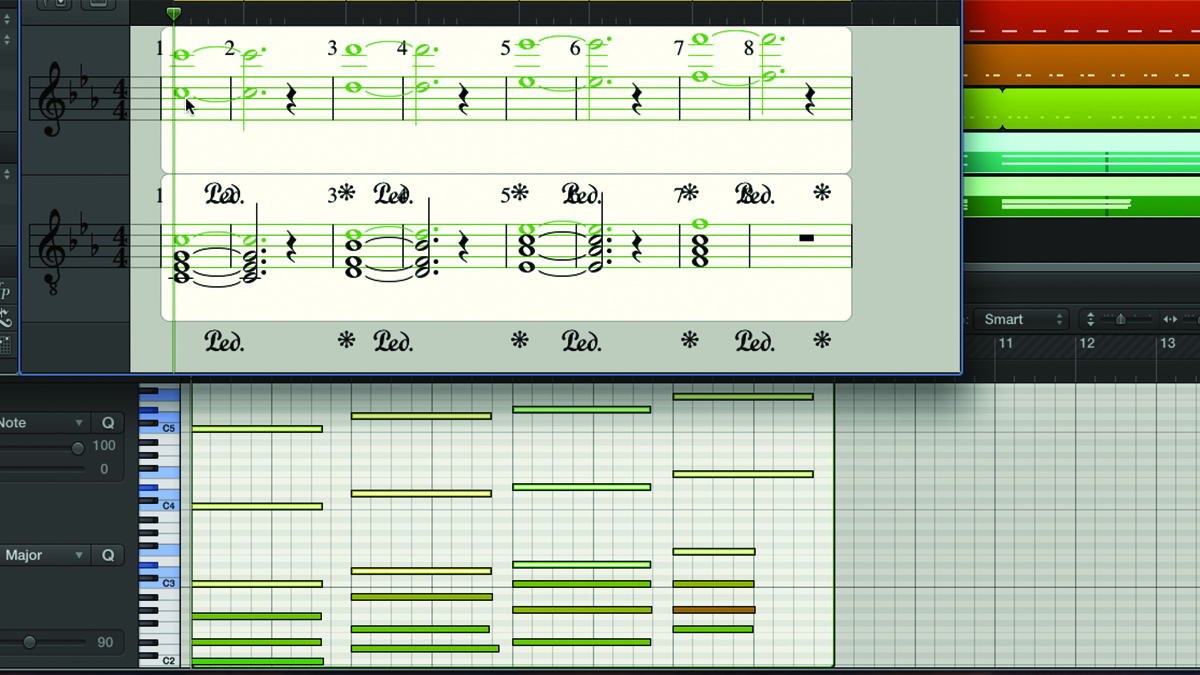

Step 4: To create Similar motion, we need to start by working out the key of the original melody. We’re in the key of C major, so let’s assign a number to each degree of the C major scale, as shown above. We then choose an interval we want to base the second part on. Thirds and sixths are the most popular options, so we’ll go for thirds as before.

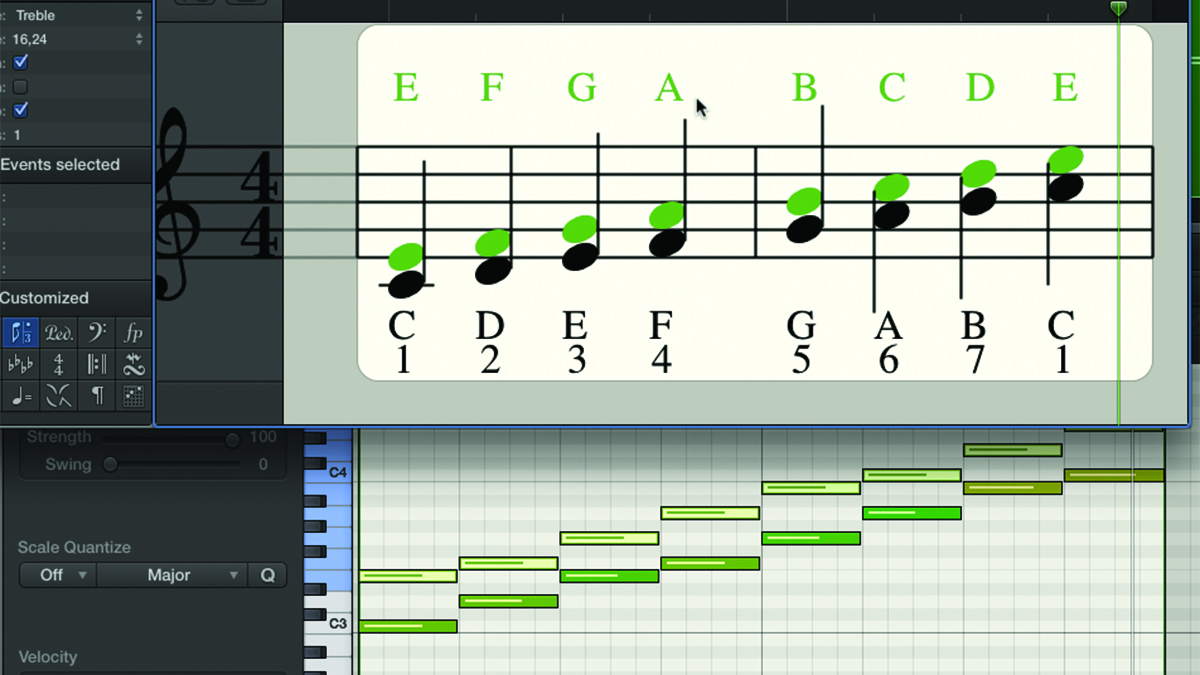

Step 5: Work out the note that’s a major third above the root note of the key we’re in, which in this case is E, a third above C. Now play the C major scale starting from E as the root note and line up this scale alongside the original as shown. This will help determine which notes to use to harmonise the melody part.

Step 6: For instance, wherever a C occurs in the first part, we need to match it with an E in the second part. Similarly, we match D to F, E to G, and so on. When we look at the intervals between each matched pair, we can see that they vary - C-E, F-A and G-B are major thirds (four semitones), but D-F, E-G, A-C and B-D are minor thirds (three semitones).

Step 7: The reason this works is that both the melody and the harmony are using notes from the same scale, just starting in different places. All the notes used in both parts are from the C major scale. This is how similar motion compensates for the key while parallel motion doesn’t, and as a result works much better harmonically. Compare the result with Step 2.

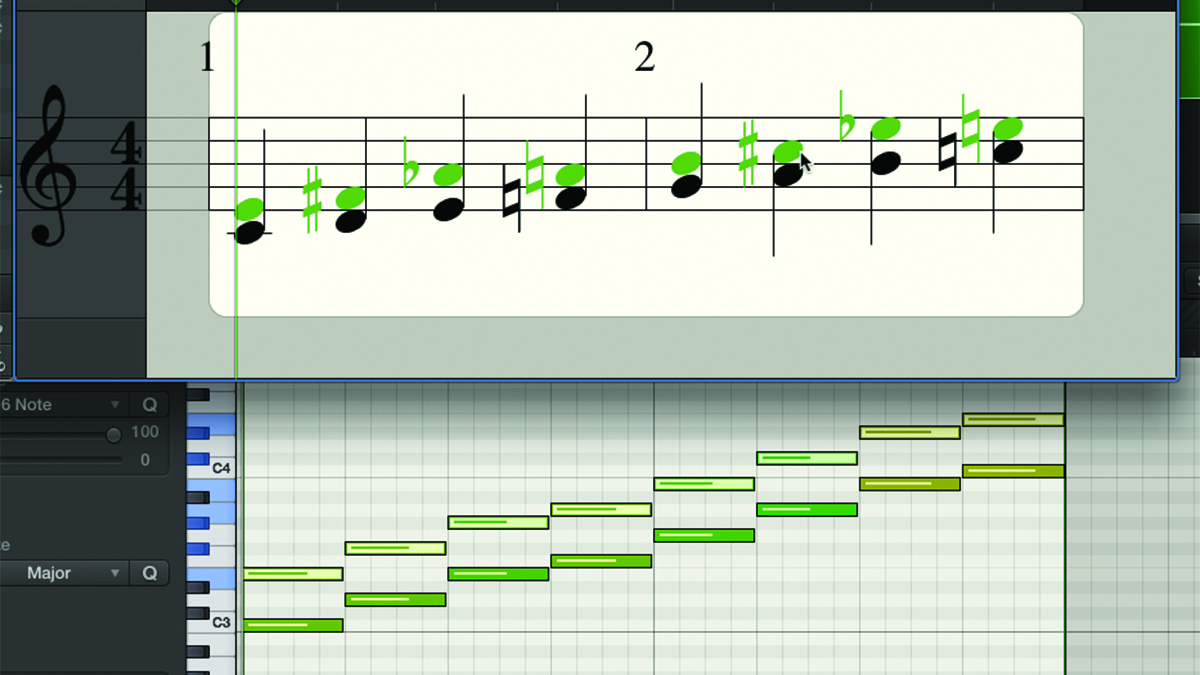

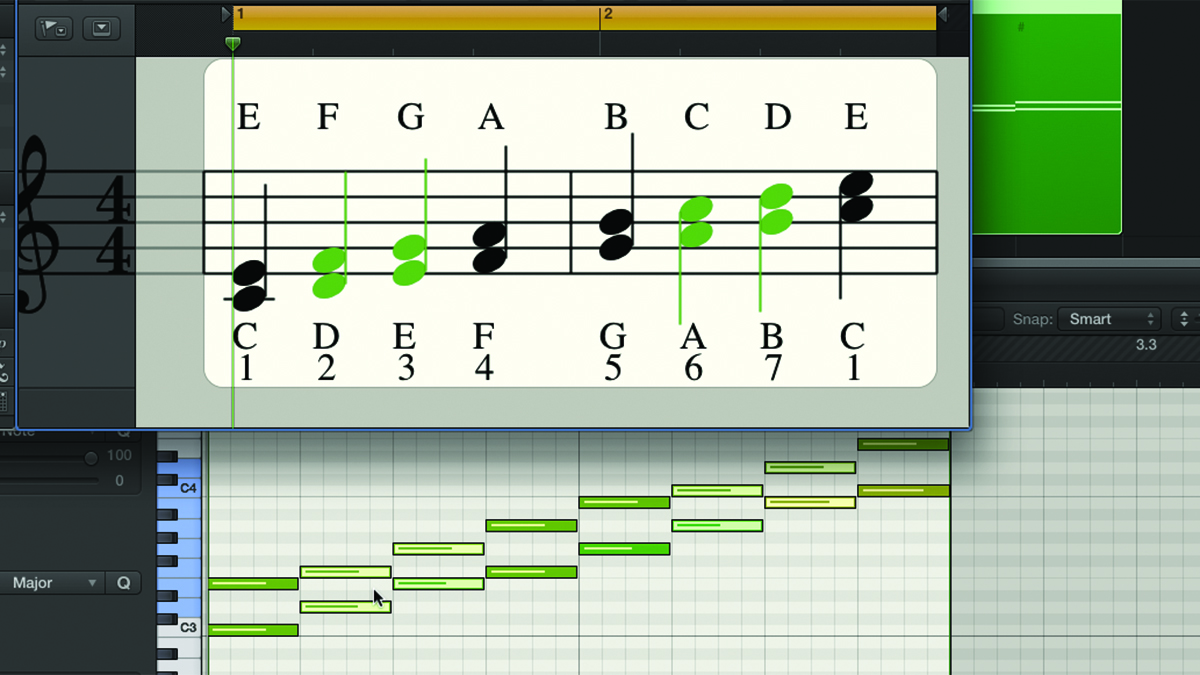

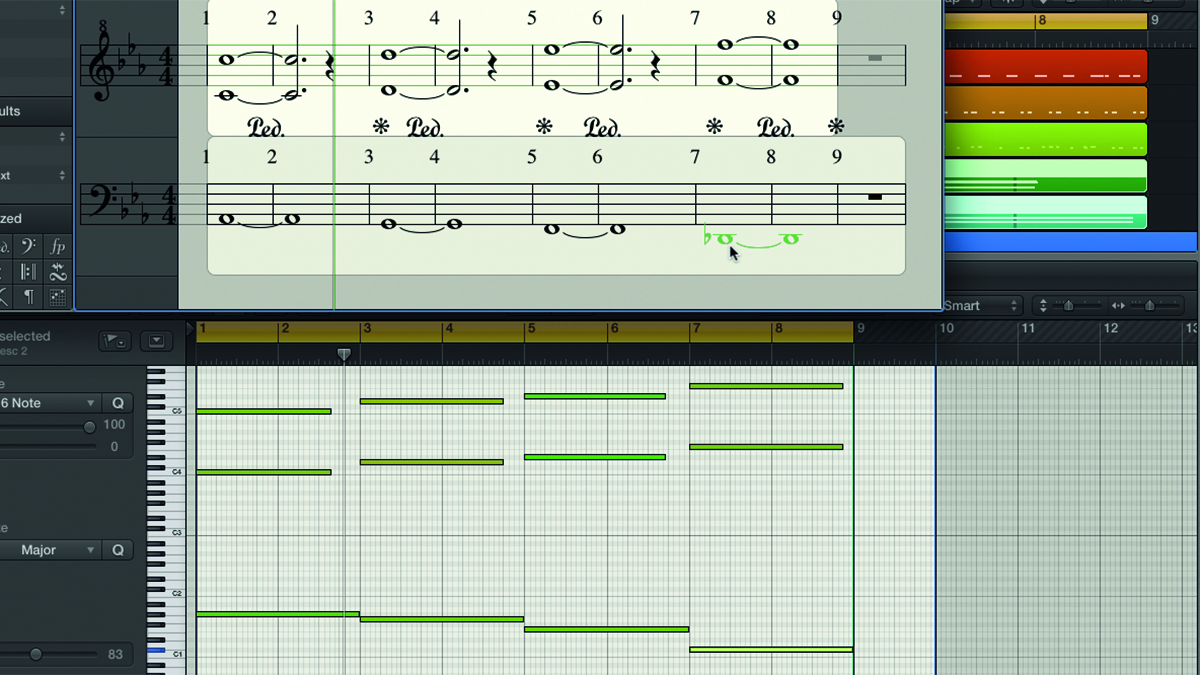

Step 8: Contrary motion is when two parts move any distance in opposite directions. As an example, bars 1-2 contain an ascending C major scale melody over a descending, half-time bassline that plays C A G F. Conversely, in bars 3-4, the melody goes down, so the bassline has to ascend, playing an upward sequence of notes: C D F G.

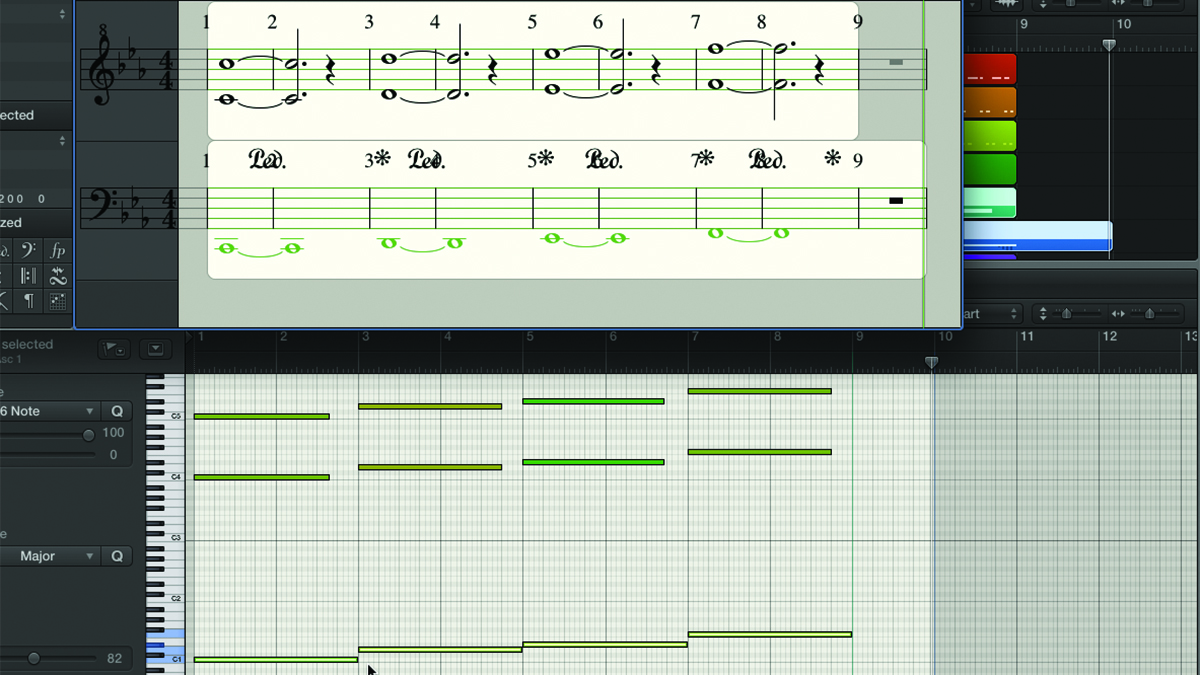

Step 9: To illustrate further, here’s a simple track made up of drums, some piano chords and a string melody. The melody is picking out the top notes of the piano chords, which are ascending: C D Eb F. These are the first four notes of the C minor scale, played in octaves for a thicker sound.

Step 10: Now we’ve added a sidechained bass playing long, sustained notes: C D Eb F in an upward motion that matches the string melody. There’s nothing wrong with this - it’s perfectly logical for the bass to follow an ascending pattern starting on the tonic, or root note of the scale - but we can employ contrary motion to do something a bit more interesting with it.

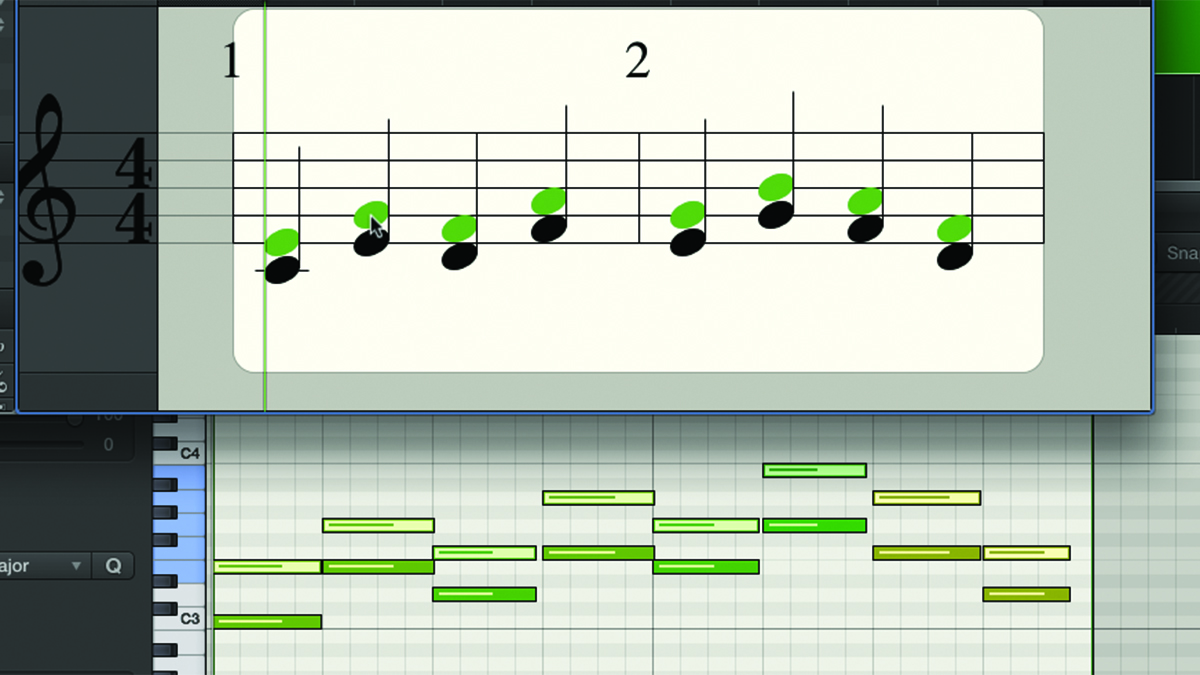

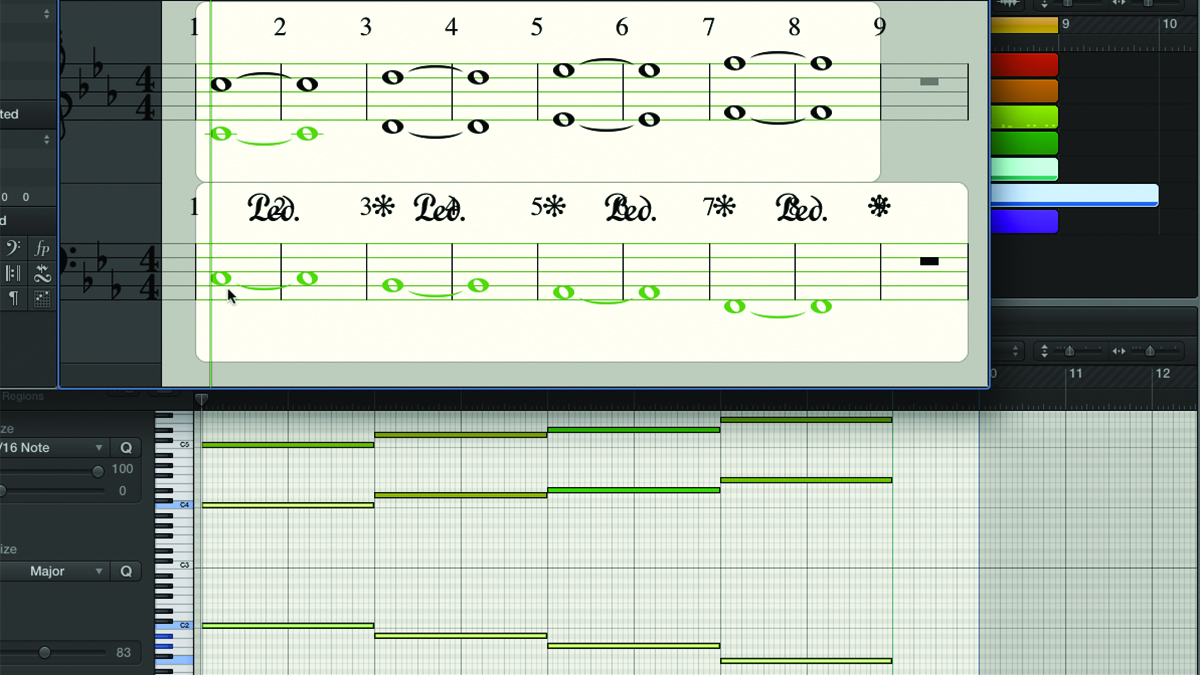

Step 11: Here’s the same track with a different bassline. While the melody maintains its upward motion, the bassline now descends: C Bb Ab F. The result is much more dramatic as the two elements move in different directions. What’s also happened is that, because it has to descend, the bass part now starts an octave higher than before.

Step 12: For a more dramatic twist, we drop the bassline down by a major third to form different chords with the piano part, while still working with the existing string melody. Here it plays Ab G F Db, effectively resulting in the progression Abmaj7 - Gm7 - Fm7 - Dbmaj7. Try it for yourself and see how many other contrary motion basslines you can come up with!

Recommended listening

Tame Impala - Elephant

Check out the end of the first solo section. The guitar and bass step downwards, while the keyboard ascends the scale in the opposite direction. A more perfect example of contrary motion you won’t find.

Rita Ora - I Will Never Let You Down

Watch out for the bass and guitar in this one - in the chorus, the guitar plays an ascending C# minor scale while the bass drops from an A down to an E.

Pro tips

On a mission

Try using the techniques detailed above to influence the relationship between other lines in your work. Purposely set out to weave, say, a vocal melody and a lead synth line together so that they either move in opposite directions or follow similar motion.

Whichever method you use, the idea is that when you set out with a particular mission in mind, you often get wildly different results than you’d expect by simply relying on instinct alone.

Mix it up

When you look at how your melody and bassline work together, ideally, you should be looking for a fairly even mix of all four types of contrapuntal motion as described here. Oblique motion will probably be most prevalent, since bass parts often pedal on the same note for several beats while the melody wanders around above it.