Iranian weapons allegedly used by Russia against Ukraine are under fresh scrutiny after Kyiv unveiled details about Western-sourced components of drones it had captured on the battlefield.

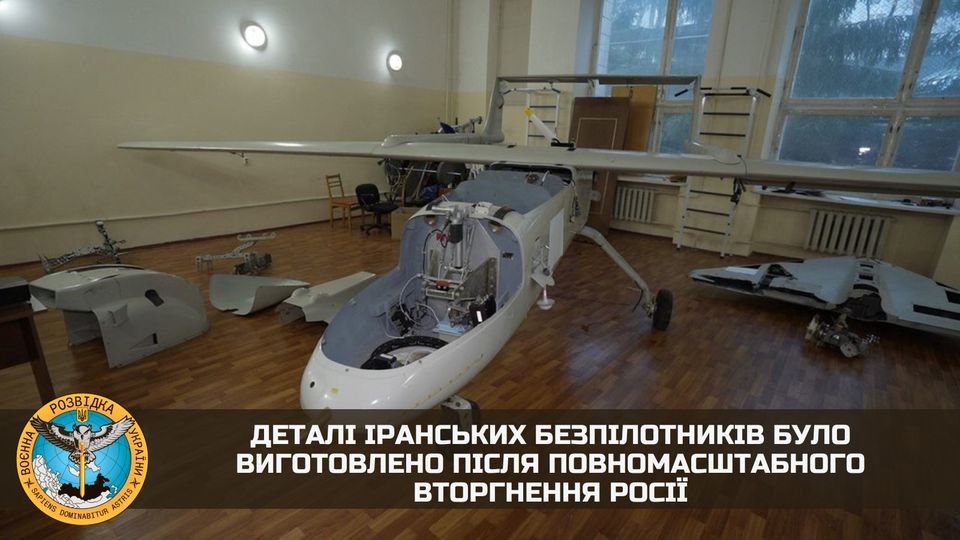

Ukraine’s defence ministry says that an Iranian-made Mohajer-6 drone used by Russian forces in the skies of eastern Europe bore dates suggesting it was manufactured in February, the month Moscow launched its attack, potentially contradicting Tehran’s claims that it had sold the weapons before the war began.

Kyiv says the drones used parts made in the United States, Austria and Japan, while Canada has conceded that engines it sold Iran could have been used for the drones.

“Ukrainian specialists are studying how foreign components ended up in Iranian drones,” the defence ministry said. “Serial numbers and data about the components have already been handed over to partner countries.”

Russia’s nine-month war against Ukraine has drawn Moscow and Tehran closer to each other than ever.

Western officials have alleged that Iran was preparing to supply Russia with ballistic missiles it could use to restock its dwindling arsenal and launch attacks on Ukrainian targets. A Sky News report cited an unnamed source alleging that Moscow had paid Iran the equivalent of €140m in cash and handed over captured British and American weapons in exchange for the combat drones. An Iranian news website affiliated with its leadership has rejected the allegation.

On Wednesday, Russia’s national security adviser Nikolay Patrushev met in Tehran with his Iranian counterpart Ali Shamkhani, ostensibly to discuss joint economic projects, evasion of western sanctions, and the war in Ukraine, according to public statements and news reports.

“Iran supports any initiative based on dialogue that leads to a ceasefire and peace between Russia and Ukraine,” Mr Shamkhani said.

Iran denied for months that it was supplying drones to Russia before admitting several days ago they were sold but that the weapons were delivered before the 24 February start of the war.

Russia has used the Iranian drones to damage Ukraine’s industrial infrastructure and terrify civilians.

Though the weapons do not appear to be decisive on the battlefield, the drones are depleting Kyiv’s resources, swarming soft targets that are nearly impossible to defend with the country’s limited number of anti-aircraft tools. The UK and European Union last month placed sanctions on Iran after its kamikaze drones hit civilian targets in Ukraine, including apartment blocks.

“They are using them against electrical facilities and they are creating power outages all over Ukraine,” said Anna Rajskaya, a Ukrainian journalist who specialises in Iran. “It affects all the major cities, including Kyiv, where there are outages of more than 10 hours a day.”

Tehran’s involvement in the Ukraine war has put it on the radar of Kyiv and the alliance of western countries supporting the nation’s defence efforts at a time when Iran is facing unprecedented domestic turmoil. A seven-week nationwide protest movement triggered by the death of Mahsa Amini, a young woman abducted by streetside morality enforcers, has left at least 328 people dead at the hands of security forces, badly damaged Iran’s economy and further soured relations with the West.

The weapons transfers to Russia have also promoted rare domestic criticism. A leading newspaper, a cleric and a former envoy to Moscow have questioned the weapons sales, accusing the government of acting against Tehran’s interests.

“You should not put all your eggs in Russia’s basket,” Masih Mohajeri, managing editor of the newspaper Jomhouri Islami, wrote.

US and UK officials have argued that Moscow’s purchase of Iranian drones could be in violation of United Nations Security Council resolutions that impose restrictions on Iran’s arms industry.

While Iranian diplomats have been coy about the weapon sales to Russia, media outlets affiliated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps have been all but boasting about them, suggesting the business deals were filling the regime’s coffers. Other Iranian voices close to the regime say Tehran has little choice.

“The reason for the close relationship between Iran and Russia is not Tehran’s excessive desire for Moscow,” Diako Hosseini, an Iranian scholar who sometimes advises the government, wrote in a tweet. “The real reason is the incessant political and economic pressures of the United States, which has left Iran with no choice but to approach Russia and China.”

Ms Rajskaya suggested that power rather than profit prompted Iran’s leadership, including supreme leader Ali Khamenei, to green-light Russian weapons sales with the full knowledge they could be used in Ukraine. Though Iran has no axe to grind against Kyiv, Tehran may have concluded it cannot afford to let Russia, among its few partners, lose the war, or for Mr Putin to go down in flames.

“Khamenei and his top officials making this decision were thinking that it doesn’t matter if it’s Ukraine or anywhere else,” she said. “They are fighting the West in another field. I don’t think it’s about money, This is about projecting power. Or maybe just Russia asked and Iran couldn’t say no.”

The political unrest in Iran as well as disagreements between Washington and Tehran have halted talks meant to limit Iran’s nuclear programme. Russia is a party to the now nearly moribund 2015 nuclear deal that removed sanctions on Iran in exchange for severe limits on its nuclear programme.

But Russian president Vladimir Putin may have now calculated that allowing Iran to advance its nuclear programme would be in Moscow’s interests.

“Putin is trying to destabilise the Western world,” said Yuri Felshtinsky, author of the book Blowing up Ukraine: The Return of Russian Terror. “The best way to do it, or the easiest way to do it, is to help the Iranians to build the bomb, or give them the bomb.”