For more than five decades, Edward Burke wielded power in Chicago politics through an army of allies that he placed in city jobs, loyalists who served as his personal intelligence network.

From his perch as 14th Ward alderman, he controlled judicial slate-making, a position that propelled his wife to rise to the job of chief justice of the Illinois Supreme Court even as he faced indictment.

Even mayors who despised Burke didn’t dare to depose him as chairman of the council’s Finance Committee, fearing the potential he had to stymie their legislative agendas.

Coming from a world of privilege, Burke entered politics as one of the youngest City Council members in Chicago history, eventually becoming its most powerful and longest-serving alderman.

Now the onetime dean of the City Council is fighting for his freedom as his 80th birthday nears.

“He’s an extraordinary figure in Chicago history, but wrapped in Greek tragedy,” said former City Hall Inspector General Joseph Ferguson. “How much more he could have done. His strengths became his weaknesses.”

On Nov. 6, Burke will finally go on trial to face sweeping racketeering and extortion charges in an extraordinary corruption case to a large extent made possible by a former City Council ally who turned on him and spent two years wired up, recording their private conversations.

Burke is accused in a series of attempts to extort legal work in property tax appeals, campaign contributions and other favors from business owners large and small, charges girded by the undercover work done by former Zoning Committee Chair Danny Solis (25th).

The Burke captured on the Solis wire — suggesting a recalcitrant businessman “go f— themselves” — marks a sharp contrast from the pin-striped Chicago charmer who dazzled colleagues with his wit, musical talents and knowledge of Chicago history.

The version of Burke caught on tape comes off more like a mobster than the genteel council dean who clung to the title of “ Mr. Chairman” and relished the trappings of power that came with it. That regal lifestyle included the car, driver and valets/bodyguards who delivered Burke to his fortress-like West Elsdon home and Powers Lake, Wisconsin, retreat.

Burke went out on his own terms earlier this year, choosing not to seek re-election to a record 15th term.

To Ferguson, the culture of impunity that Burke cultivated ultimately led to his political demise. Though he learned Spanish as the demographics of his Southwest Side ward changed, he continued to do business the same old way.

“The world changed and the standards changed, but the practices didn’t change. This is the Chicago way of doing business,” Ferguson said.

Burke, a “constant companion” of his father

Burke learned the game of Chicago politics from his father, former Ald. Joseph P. Burke.

“They were remarkably close. They were more friends than they were son and father,” said former state Rep. Dan Burke (D-Chicago), the former alderman’s brother.

“He was a constant companion of my father,” Dan Burke continued. “Political meetings. Social gatherings. Everywhere. That’s how he became so sophisticated in his political experience. He dressed formally. He was an adult by the time he was 8.”

In the basement of the Burkes’ Canaryville bungalow was a “great upright piano.” Young Ed would play and sing along, entertaining everyone at his father’s many parties.

“He was probably a child prodigy. He could hear a song and play it and accompany anybody,” Dan Burke said.

Ed Burke followed the classic Chicago path for a son of politics and privilege. Visitation Parish. Quigley North Seminary. DePaul University, where he later attended law school while moonlighting as a Chicago police officer assigned to the state’s attorney’s office.

“I remember one older cop that I was assigned to work with who gave me a piece of advice,” Burke said in a 2014 interview for a University of Illinois Chicago oral history of former Mayor Richard J. Daley. “‘Kid, you better be careful whose ass you kick on the way up the ladder, ‘cause you never know whose ass you’re gonna have to kiss on the way down.’ A lot of wisdom in that.”

Burke routinely drove to law school in a carpool that included Richard M. Daley, son of arguably the most powerful big-city mayor in American history. Like young Daley, Burke managed to avoid being drafted at the height of the Vietnam War, instead joining the Army Reserve.

During the tumultuous year of 1968 that included the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Burke’s personal life suffered a tragic blow.

His father died of cancer at 56.

The stoic Ed soldiered on.

“I’ve never seen him cry,” Dan Burke said. “He holds up...He puts on his suit of armor. I was more concerned about my mother. Everything changed dramatically. My mother had to go to work just to make it. She had never worked or drove a car.”

“He took the bar exam the first day of my father’s wake and passed it on the first go-round, unlike poor Richie Daley,” Dan Burke said.

Burke’s entry into politics

Only 24, Burke was determined to pick up his father’s political mantle.

His father’s precinct captains chose him to fill the job of 14th Ward committeeman. Then in 1969, Burke defeated six opponents in a special aldermanic election.

“I’m not foolish enough to think that I got elected at 24 because of any great skill or talent that I had,” Burke said in the 2014 interview, referring to his selection as ward committeeman. “I was elected because I was my father’s son, and people respected him and were willing to give me the benefit of the doubt, that if Joe Burke was a good public official, maybe his kid could carry on in the way he would want.”

Thus began an extraordinary career that would last for 54 years.

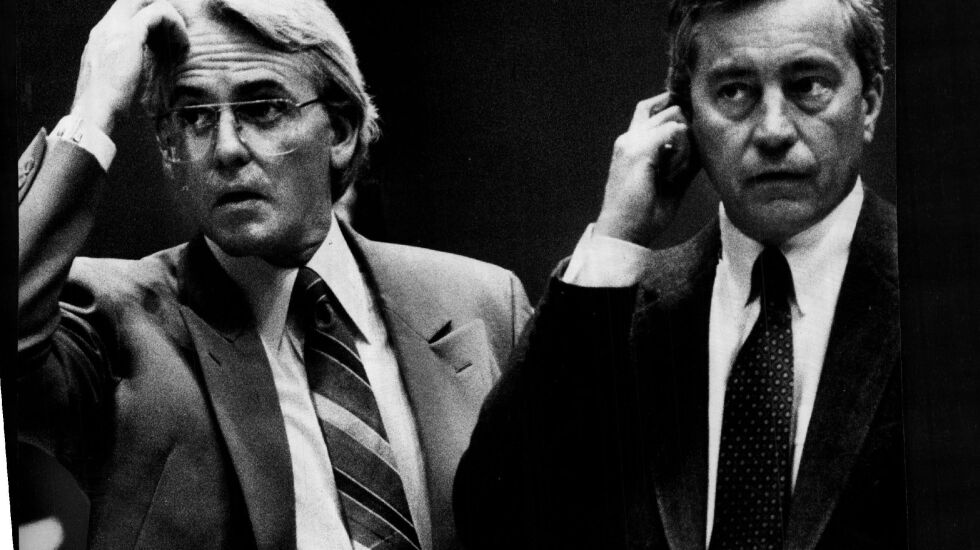

Burke quickly forged a political partnership with Edward “Fast Eddie” Vrdolyak (10th). The “Young Turks” led the “Coffee Rebellion” (so-named because the rebel aldermen bought coffee mugs to promote themselves) that pushed back against the iron-fisted control of then-Finance Chairman Tom Keane (31st).

The “two Eddies” were also part of, as former Mayor Jane Byrne put it, the “cabal of evil men” whom she accused of “greasing” a taxicab fare increase before cutting her own political deal with Burke and Vrdolyak, and turning the City Council over to them.

It was during that time that Vrdolyak convinced Burke to launch what would amount to a suicide mission in a failed Democratic primary bid to stop Richard M. Daley from becoming state’s attorney. The animosity between Daley and Burke would never subside.

Harold Washington’s historic victory over Byrne and Daley in the 1983 Democratic mayoral primary was a watershed moment in Burke’s career, one that he would live to regret.

Reacting to the blunt tone of Washington’s inaugural address at Navy Pier, Burke and Vrdolyak organized 29 mostly white aldermen against Chicago’s first African-American mayor. The battle royal known as “Council Wars” would drag on for three years — until special aldermanic elections in four wards gave Washington control over the council.

Burke’s allies and co-workers insist that the fight with Washington was about power and not race. But Burke’s extremist statements and positions while attempting to thwart the mayor’s every move would come back to haunt him.

Council Wars fallout

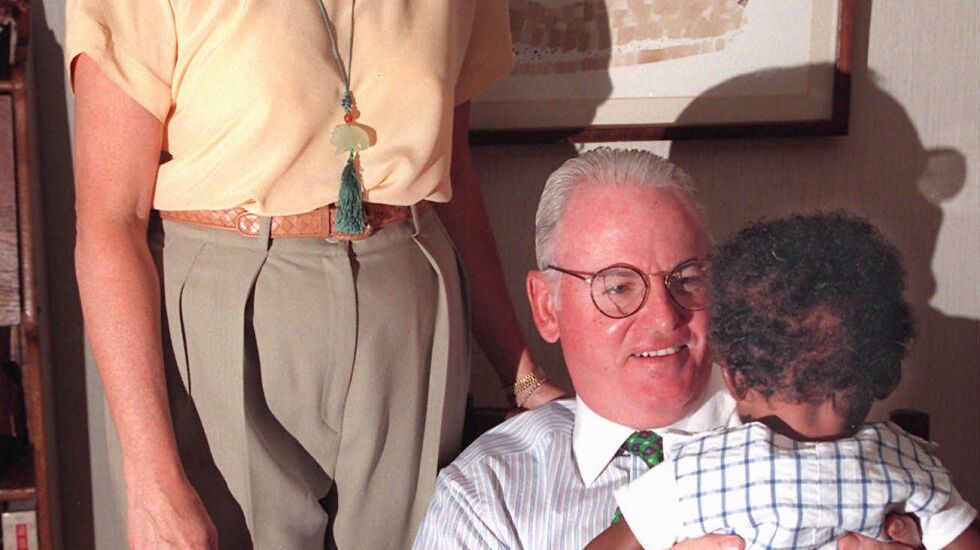

He would never live down the racist image, not even after adopting an African-American baby born to a mother battling drug addiction. He and his wife, Anne Burke, at the time an Illinois appellate judge, won a highly publicized custody battle with Tina Olison, the biological mother of “Baby T,” and raised Travis into a college-educated adult who now works as a railroad engineer.

Olison recalled Burke pulling up to her home with his driver and bodyguard while dropping off Travis for visits during the lengthy court fight.

“He was always making the same smug face at me,” said Olison. “He was hard to read. You always looked at him straight in the face, and he’d look off. That same face you see on TV — like, ‘I’ll have nothing to do with you.’ That face that you just can’t read.”

Jacky Grimshaw, who served as Washington’s director of intergovernmental affairs, said she was not fooled by the “Baby T” adoption or Burke’s subsequent attempt to moderate the extremism he showed during the 1980s.

“Say Eddie Burke to anybody. Council Wars is the first thing they think about. That is his legacy,” Grimshaw said in November 2022. “Harold (Washington) would come right out and say that Vrdolyak was about the green, but that Burke was a racist. He didn’t pull any punches about that.”

Former Ald. Helen Shiller (46th), a Washington ally, added, “You can’t defend and protect institutional racism and say you’re not engaged in it.”

Now-retired Ald. Roderick Sawyer (6th) said he assumed that Burke was a racist — until his father, former Mayor Eugene Sawyer, “educated me about the political process and why people were doing the things they were doing.”

“I had the opportunity to work with Ed Burke for twelve years. He was extremely helpful to me when he didn’t have to be. He never showed a racist bone in his body,” the younger Sawyer said.

Dan Kubasiak worked as Burke’s Finance Committee chief of staff during three and a half years that included Council Wars. He called Burke “one of the last old-time ward committeemen who looked at his ward as being his responsibility.”

Kubasiak, who became a judge with Burke’s help, said he sat in on countless meetings between Burke and his constituents. Never once did he hear Burke say, “If you do this, I’ll do that.”

“There were probably thousands of people who needed a job, needed health insurance or some service in the ward. Not knowing where to turn, they came to him and, if he could help, he would,” Kubasiak said.

Burke the survivor

In 54 years as ward committeeman and 53 as alderman of a now-majority Hispanic ward, Burke survived numerous threats to depose him as Finance Committee chair by mayors with whom he subsequently reached political accommodation.

He survived federal investigations that had threatened to undercut his power base, once even by blaming a dead man for ghost-payrolling irregularities on his committee payroll.

“I always thought he had a special relationship with the FBI. I had no idea what it was,” Shiller said.

Burke’s impact on landmark legislation affecting the everyday lives of Chicagoans cannot be overstated.

Look no further than the ban on indoor smoking in public places that he championed, fueled by his father’s death from lung cancer. There was also Chicago’s carbon monoxide mandate, and the requirement that dogs and cats be spayed or neutered.

A notorious headline hog, Burke once summoned the late TV personality Jerry Springer to a 1999 City Council hearing to explain the domestic violence, lewd discussion and behavior on Springer’s talk show.

“It got international attention. He really stuck his neck out for that,” said the Rev. Michael Pfleger, who had asked Burke to put the Springer show on notice. “In my mind, that became the turning point, the beginning of the downfall of the Jerry Springer show.”

Behind the scenes, Burke was a master of intimidation. And it wasn’t always confined to businesses seeking city subsidies whose legal work he was allegedly demanding in return for putting their items on the Finance Committee agenda.

He operated like City Hall’s version of J. Edgar Hoover. He had a file on everybody. He knew where the bodies were buried. He could embarrass almost anybody with tentacles that extended to every city department.

Retired Ethics Committee Chair Michele Smith (43rd) recalled her chilling first — and only — private meeting with Burke after Anne Burke suggested during their encounter at a political function, “You should talk to my husband.”

“At one point, his voice dropped and he told me something he could only have known if he had read my divorce file,” said Smith, a former federal prosecutor.

“That told me he had access to go find stuff on people. He had to know somebody in Cook County [government]. He wanted to let me know how powerful he was. That he could find out maybe something he thought was embarrassing. It told me enough that I never talked to him unless I absolutely had to.”

Burke has survived prostate cancer and the death of his son Emmett in a 2004 snowmobiling accident.

Even though his name is no longer on the door of the firm once known as Klafter & Burke, Dan Burke said, “He goes to the office…dressed like he’s going to a dance every day…He’s pretty remarkable.”

“A man who had everything”

Former Mayor Lori Lightfoot humiliated Burke at her first City Council meeting in 2019, when she essentially told Burke to sit down and shut up as he needled her over procedural issues.

“Once he started, I knew I had to put him back in a box and do it very decisively. And so he never really did it again, directly,” she said.

Although the animus between the two dates back decades, Lightfoot recalled twice over the years when Burke reached out to her through a third party to offer her judgeships, once for a circuit court position and more recently for the Illinois Supreme Court.

Lightfoot, who says she’s never wanted to be a judge, declined both times.

“He was a guy that liked to collect favors from people,” Lightfoot said. “And if he did you a favor, then you owed him something. I did not want to be in that category.”

Former Ald. Mary Ann Smith (48th) said she views Burke’s historic career and stunning fall from grace as a “classic Shakespearean tragedy.”

“So articulate and so charming…This is a man who had everything. Brains, family, high school seminary education, the classic Chicago formula. He had privilege regarding the whole Vietnam thing…All of these things could have been obstacles,” Smith said.

“To see him throw it away because he couldn’t stand having someone else not pay homage to him to get a driveway permit…That’s what it boils down to — a complete obsession with control and power,” Smith continued. “It wasn’t about the money. It was about power and control.”