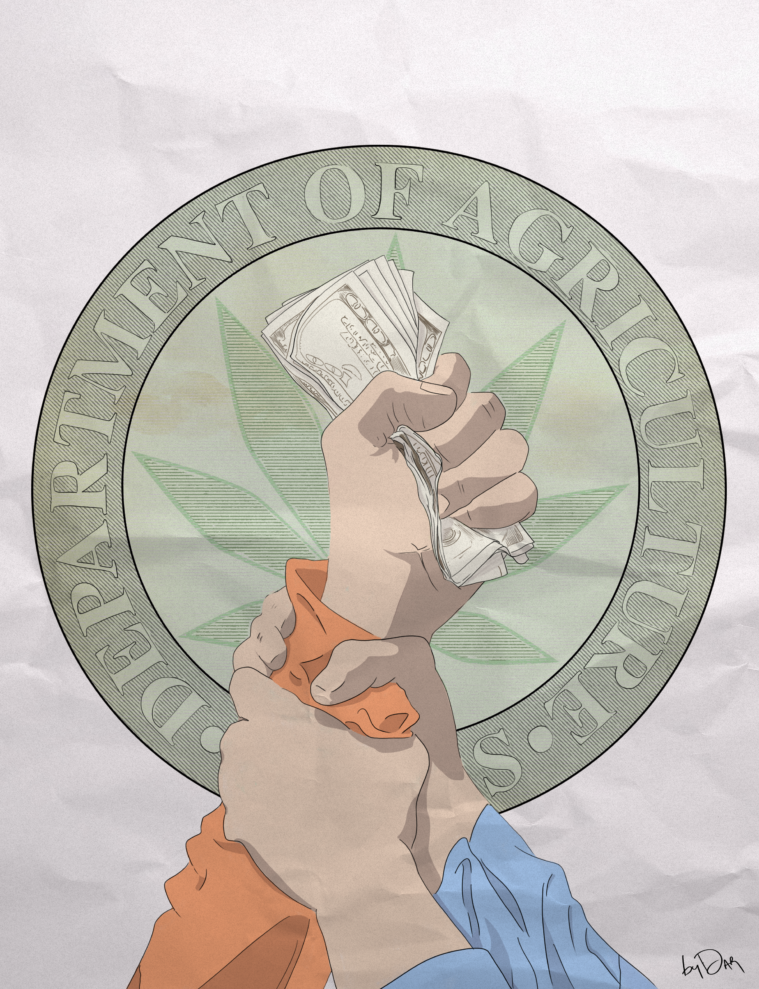

On June 10, 2019, Governor Greg Abbott signed a law to legalize state hemp production and sales as soon as the Texas Department of Agriculture adopted rules to regulate the potentially lucrative new industry. In the ensuing race to score the state’s first licenses, several hemp enthusiasts forked over tens of thousands of dollars for insider advice from Todd M. Smith, a lobbyist and the longtime number-one political advisor to Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller.

Smith cultivates a tough-guy persona. “I AM Danger!” he once tweeted. “I don’t tolerate losing or fools—especially fools that lose.”

Smith and Miller, a real life rodeo cowboy, have been a team since the Stephenville Republican first won a Texas House race in 2000. Miller has given Smith—his top client—$1.5 million of the $6.6 million in political consulting fees he’s reported since 2000. During that time, Smith, who doubles as a lobbyist, received at least $26 million more from lobbying clients.

But in 2019 and 2020, Smith actively sought clients who were seeking to curry favor with Commissioner Miller himself as the Texas Department of Agriculture drafted those hemp rules, according to public records and interviews obtained by the Texas Observer. This sparked multiple potential conflicts of interest for Smith—who allied himself closely with Miller’s agency almost as if he were a high-ranking Ag Department employee, setting the stage for what indictments later described as a series of shakedowns.

One of Smith’s first hemp clients was Plano-based lawyer William Cavalier of the startup Green Grow Farms Texas, LLC, according to Smith’s lobbying reports. As Cavalier began building the business in July 2019, Smith told him he could better position himself to obtain a hemp license by hiring him as a lobbyist and paying him to conduct a public opinion poll on hemp that would be presented to Miller’s agency, according to a warrant issued much later for Smith’s arrest. Cavalier’s company paid Smith $26,500 for “Texas Department of Agriculture Survey Research” in August 2019, the warrant says.

By early 2020, seven hemp clients had paid Smith up to $370,000 to lobby Miller’s agency, according to Smith’s lobbying reports, which report income in ranges. This income was crucial to Smith, who declared personal bankruptcy in 2015 and has declared himself to be virtually destitute in his 2022 divorce case.

Cavalier and several other clients now claim that Smith billed them for polling he never conducted. He and others also were dismayed when Miller’s agency later began handing out unlimited hemp licenses.

The cost? $100.

Miller’s friendship with Smith began more than two decades ago, when the owner of a landscaping and nursery business in the city of Stephenville ran for the Texas Legislature in 2000. Miller is a champion calf roper who has used hemp-based cannabidiol (CBD) oil to treat related aches and pains. Miller has forged his political identity through cage-rattling comments, using his power over school lunch programs to advocate for the restoration of soda machines and deep fryers in Texas schools despite concerns about childhood diabetes, likening Syrian refugees to rattlesnakes, and calling, via his campaign, for nuking Muslim countries.

Smith has always been Miller’s biggest fan.

“I’m a friend of Sid Miller. I love Sid Miller,” Smith told the Austin American-Statesman in 2015 after Miller first assumed statewide office. “He’s basically been type-cast to be agriculture commissioner.”

Both men surround themselves with colorful characters and have histories of legal and ethical brinkmanship.

The Texas Rangers, Travis County prosecutors, and the Texas Ethics Commission have repeatedly pored over the two men’s political committee reports and intertwined personal, financial, and lobbying disclosures. Over the years, the Ethics Commission has levied at least $26,250 total in fines against one or the other of this dynamic duo.

In 2009, it fined Miller $1,000 for failing to comply with a law that requires state officials to disclose any interests that they co-own with lobbyists. Miller had neglected to mention that he and Smith both owned shares in two companies: ECampusnation, LP and the political robocall firm E-Communications, Advantage, Inc.

As the duo planned Miller’s campaign for agriculture commissioner, ethics commissioners levied $2,750 in fines against his campaign for more faulty reports in 2013 and 2014. Regulators found that Miller’s campaign didn’t balance its checkbooks, spent more than its reported assets, and failed to report contributions and a loan repayment. That investigation also uncovered thousands of unreported dollars moved back and forth between Miller’s private landscaping businesses and his campaign account. Miller’s campaign kept most of its funds in an online stock brokerage ETrade account, which is legal. But at the end of 2012, Miller “took personal possession of the entire ETrade account,” then worth almost $64,000, according to the Ethics Commission.

In other words, Miller moved funds between his campaign, business, and his personal accounts almost as if they were all the same. It’s illegal to convert campaign funds for personal use and it’s illegal for candidates to accept campaign contributions or loans without properly reporting them under state laws. Miller was not charged with any crime.

Miller’s poor record-keeping seemed to befuddle even the ethics police. Was the unreported $3,366 that Miller Nursery & Tree Co. transferred to Miller’s campaign a political contribution or a loan? When Miller legally invested campaign funds in the stock market, did the resulting market gains accrue to his campaign or to himself? The Texas Ethics Commission did not tackle these key questions in its rulings.

When Miller ascended to Ag Commissioner in 2015, there already were signs that Smith, his political consultant, might be selling lobbying clients access to his political boss. Smith client Richard Branson of San Antonio told the Austin American-Statesman that Smith advised him in 2014 to promote his physician assistant business by contributing to Miller’s campaign and getting appointed to the Department of Agriculture’s Rural Health Task Force. In a meeting Branson said that Smith arranged, Branson contributed $1,000, but failed to land the appointment.

Seeking to promote rural telemedicine, another Smith client, Rick Ray Redalen—a self-described “maverick doctor” and owner of Quest Global Benefits—contributed $17,000 to Miller’s campaign. Miller appointed him to the Rural Health Task Force in 2016. Redalen got that appointment despite already having had his medical license suspended in three states for alleged substance abuse and psychiatric problems. Redalen also had a criminal record: He pleaded guilty to assaulting his wife with a rifle butt the year before her 1987 suicide and was convicted of perjury in a case involving his marriage to his former stepdaughter.

Around the time that his lobby clients were seeking task-force appointments, Smith’s life was coming undone. He filed for personal bankruptcy in 2015 and recently disclosed that the IRS is auditing both his 2015 and 2016 tax returns. Even as he was careening into insolvency, Smith donated tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of consulting services to Miller’s campaign.

Upon taking office, Ag Commissioner Miller then created new assistant commissioner posts, awarding one with a $180,000 salary to Smith’s wife, Kellie Housewright-Smith.

The specially trained Public Integrity Unit of the Texas Rangers investigates complaints about public officials. Such investigations are rare: Rangers generally must present evidence of potential crimes to a district attorney before investigating; many prosecutors think twice about tackling powerful officials. But the Rangers investigated complaints about two taxpayer-funded trips with nebulous public purposes that Miller took soon after becoming commissioner. In one trip, Miller flew to Oklahoma to get an experimental painkiller dubbed the “Jesus Shot” by an Oklahoma doctor who claimed it took away all pain for life. That doctor had lost his Ohio medical license and had been convicted on federal tax evasion charges. After declaring that “criminal intent would be difficult to prove,” Travis County prosecutors declined to pursue charges against Miller.

The Texas Ethics Commission did fine Miller $500 for violating campaign finance rules by spending $1,021 in state money to fly to the National Dixie Rodeo in Mississippi (where he won $812 in prize money). Miller paid for his own hotel and rental car with a personal credit card but also reported those expenditures as campaign expenses. After the media dug into both trips, Miller reimbursed taxpayers. The Rangers never released the results of their investigations and Miller was never charged with a crime.

Each time, Smith came to Miller’s defense. He once claimed that the agriculture commissioner is in character—and on the clock—24/7 for voters and taxpayers. “He can’t flip a switch and say, ‘I’m no longer the agriculture commissioner here,’” Smith told the Texas Tribune.

Smith has had his own run-ins with the Texas Ethics Commission. It fined him $5,000 in 2017 for failing to disclose lobbying fees paid for with political contributions. In that case, the commission noted that Smith “had failed to timely file 53 reports with the Commission, for which the Commission assessed $14,500 in civil penalties.” Still, Smith did not pay up, forcing the state to sue to collect.

By 2019, when the hemp rules were being drafted, Smith was a working lobbyist deeply aligned with a major state agency. Interviews show that one of Miller’s own employees referred a potential hemp client to Smith.

Other state employees sent official letters to Smith’s clients on agency letterhead at Smith’s request, according to allegations made in a pending criminal case.

“This is a lobbyist’s dream come true,” said Craig Holman, a government affairs lobbyist at Washington-based Public Citizen, about Smith’s role. “He’s advising his boss what regs to write and telling clients, ‘If you wanna come out smelling good, then you’ve got to hire me.’”

Holman said few laws are written to govern conflicts by consultants who hold no formal position of power. The only ethical limits in such cases, he said, are typically imposed by the consultant’s own political boss.

A Texas conflict law generally prohibits lobbyists from representing a client when doing so might injure another client or employer. Lobbyists must promptly report potential conflicts to affected parties and to the Ethics Commission. That agency told the Observer that Smith has never filed any such conflict disclosures. Maximum civil penalties faced by violators are a $2,000 fine and two-year lobby suspension.

“This is a lobbyist’s dream come true.”

Miller has claimed he knew nothing of Smith’s hemp-lobbying efforts in 2019. Miller and Walt Roberts, his assistant commissioner of communications, did not respond to repeated requests by the Observer for comment.

By late 2020, Miller was not only Smith’s top client; he was his patron saint, records show. Smith’s marriage was falling apart and he moved out of his family home in Austin. Thanks to Miller, Smith had a place to go. From November 2020 through April 2021, Smith testified, in his 2022 divorce case, “I resided at no cost at a home … in Coupland, Texas, that was owned by Commissioner of Agriculture Miller, and he let me live there rent-free.”

During the time Miller’s agency was hashing out state hemp regulations in late 2019 and early 2020, his chief political consultant was working to dig himself out of one deep hole, records show. The potentially lucrative new hemp industry presented a money-making opportunity.

Green Grow Farms initially paid Smith $25,000 for lobbying in August 2019. By the end of 2020, Smith’s fees had ballooned to as much as $100,000. Lobbyists such as Smith are legally required to make monthly reports of new clients. But Smith didn’t report getting any hemp clients until December 2019—six months after the hemp law’s enactment. Then, Smith suddenly disclosed Green Grow Farms and three other hemp clients: The Edmund Group, L&L Farms, and WPCP Capital. By early 2020, Smith reported that seven hemp clients had paid him up to $370,000.

Perhaps Smith never intended to report those hemp clients at all: His disclosure came two months after an activist publicly accused him of breaking the law.

Bastrop hemp evangelist Nathaniel Czerwinski said he first met Smith through Texas Department of Agriculture information specialist Richard Gill at a hemp conference in Corpus Christi. Czerwinski told the Observer in an interview that Gill recommended meeting Todd Smith (Gill did not respond to a request for comment). Czerwinski said several contacts with Gill and Smith ensued, culminating in a meeting at an Austin IHOP along Interstate 35. There, Smith handed Czerwinski an invoice for a $25,000 lobbying contract to fund a hemp poll. After friends talked him out of paying the bill, Czerwinski publicly denounced Smith.

During an October 2019 hearing to gather public input on forthcoming Texas hemp rules, Czerwinski stepped up to the mic and dropped a bombshell.

“I have been lied to by lobbyists and a chief government official over this [hemp licensing] issue,” he testified. “I was even offered a $25,000 shortcut to the front of an imaginary list for hemp farming by one of the chief lobbyists for Sid Miller.”

Czerwinski told the Observer that soon after he denounced Smith, “The Texas Rangers came knocking on my trailer door.”

In February 2020, Smith made a correction to his 2019 lobbying report, claiming that he “inadvertently” neglected to report representing a man named Keenan Williams. (He also reported Williams as a repeat client in 2020.) At first glance, Williams seemed to have nothing to do with hemp: He was a Dallas-area campaigner for former President Donald Trump who worked the motivational speaker circuit, often recounting how he reformed himself from being a violent drug abuser by reading hundreds of books behind bars.

But records show that Williams also recruited hemp clients for Smith and helped raise hemp-related campaign funds for Miller, too. Indeed, Williams allegedly cultivated Dallas-based Vinson Capital, which made the largest hemp payments to Williams and Smith, according to court records (though Smith never reported Vinson as a client).

According to an affidavit, on August 18, 2019, Williams told the firm’s principal, Andre Vinson, that he worked with Department of Agriculture leaders and could deliver one of just 15 state hemp licenses for $150,000.

A week later, Vinson Capital’s Hannah Smith gave Williams $25,000 in cash, a $15,000 check payable to Williams, and a $10,000 check made out to Todd Smith, criminal warrants allege. Williams told the Rangers that he passed $15,000 of that cash to Todd Smith, claiming that Smith would use it to survey voter hemp opinions as a prerequisite for licensing.

“Hey my friend,” Todd Smith texted to Williams on August 24, 2019, according to a warrant. “Now that I have accepted compensation, I need to register with the Texas Ethics Commission. For whom do I register?”

Williams and Vinson deepened their financial ties on August 27, 2019, forming a corporation together: South and West Land Corporation, LLC. Vinson and Hannah Smith then drove to Austin on November 6, 2019 and handed another $30,000 in cash to Williams outside El Mercado Restaurant on Lavaca Street—two blocks from the Department of Ag headquarters, according to arrest warrants later filed against Williams and against Smith. Williams later told the Rangers that he delivered $10,000 of that money to Todd Smith in front of the Ag building on Congress Avenue shortly before escorting his Vinson Capital visitors inside for a meeting.

“There is no way in hell, you can tell me—or anyone can tell me—that the commissioner had no idea what was going on.”

If Vinson was paying Smith to lobby, then Smith needed to report that contract to the Texas Ethics Commission. Failure to register as a lobbyist can result in a Class A Misdemeanor, civil fines, or revocation of lobbying privileges. Public records indicate that Smith never registered as a lobbyist for Vinson Capital or South and West Land Corporation.

That day’s agency visitor logs, which do not record times, list eight entries. Meanwhile, Commissioner Miller’s calendar that day lists three separate hemp appointments. Miller scheduled a conference room for a “Hemp discussion” from 2 p.m. to 3 p.m. followed by a meeting in the commissioner’s office with Williams from 4 p.m. to 5 p.m.

Miller ended the day with supper at the Land and Cattle Restaurant, his calendar shows. His dinner companion: Williams, who signed the visitor log twice that day, including the last entry of the day. Whatever transpired that day appeared to satisfy Vinson Capital, which contributed $20,000 to Miller’s campaign on November 18th.

Not all would-be hemp licensees swallowed the story that they needed to pay hefty lobby fees to obtain a license. Karla Nunn said Williams pitched her at a Collin County bakery in August 2019. Nunn told the Observer that she knew he “was off” when Williams said that his political connections could secure a hemp license for $25,000.

At the same time, Reggie Harris and an Air Force veteran from Oklahoma named James Johnson were seeking a hemp license for a company called CCI Med Group. CCI was having trouble landing an agency meeting to seal the deal, despite the encouraging letter that it received in September 2019 from Commissioner Miller.

“My team and I look forward to working closely with you in the coming weeks to determine how best to implement your ideas as we write the rules which will provide my department with regulatory oversight of the Hemp industry,” the letter said.

Confronting bureaucracy head-on, Johnson said that he drove from Oklahoma to the Texas Department of Agriculture’s headquarters on October 9, 2019, hoping to parlay Miller’s letter into a meeting to break CCI’s license logjam. Johnson said that he spoke to two top Miller aides, Randy Rivera and Dan Hunter, who told him that they didn’t know anything about Miller’s letter.

It’s hard to know if Miller or his agency approved the letter to CCI—or if another agency employee or someone else sent it. Smith has been accused of coordinating letters from the agency to his clients in a pending criminal case. Asked about this, Rivera told the Observer that the agency’s general counsel instructed him not to discuss matters under investigation.

But Johnson, the veteran who drove from Oklahoma to meet with Miller, does not believe that Miller was in the dark.

“There is no way in hell, you can tell me—or anyone can tell me—that the commissioner had no idea what was going on,” Johnson said in an interview. “He may have tried to distance himself from it as much as possible. But this [Smith] is his campaign manager.”

Smith was indicted in January 2022 on a felony charge of commercial bribery, which could result in six-to-24 months in state prison. Both Smith and Williams have also been charged with third-degree felony theft with potential penalties of two to 10 years. Arrest warrants allege that one or both of the defendants participated in an illegal scheme to provide hemp licenses to Vinson Capital, Green Grow Farms, Nathaniel Czerwinski, Karla Nunn, and others in exchange for money. No one else has been charged to date. Williams and some of Smith’s clients appear to be cooperating with the investigation.

“We are holding accountable powerful actors who abuse the system and break the law,” Travis County District Attorney José Garza said in a press release.

Williams’ attorney Thomas Fagerberg declined to comment, citing ongoing negotiations with prosecutors.

Following Smith’s arrest, his number one political client, Miller, initially insisted that Smith had done nothing wrong. He distanced himself from Smith, telling the Texas Tribune, “That was Todd, between him and his clients.”

But soon after his friend’s indictment, Miller announced that his campaign and Smith were parting ways.

Smith declined to discuss the indictment with the Observer, repeatedly saying, “I’m not talking about it.” When his own attorney asked about the charges during Smith’s April divorce hearing, Smith said the charges “are politically-motivated and are geared to cause political harm to one of my clients.”

Prosecutors traditionally avoid filing criminal charges against politicians or their allies right before an election. Some Miller supporters say that Smith’s 2021 arrest was intended to weaken Miller just as he was deciding whether to run for re-election or to challenge Governor Greg Abbott in 2022. The Travis County District Attorney’s Office did not respond to requests for comment on the case’s timing. Smith was scheduled for a pretrial hearing in June, and Williams had a hearing scheduled in July.

“It really pisses me off to see people misuse their office. They are scamming people who can’t afford to be scammed.”

Case indictments and arrest warrants allege that Miller’s state employees sent letters to Smith’s clients at his request. Nathaniel Czerwinski said that Todd Smith solicited him as a client after the two were introduced by one of Miller’s employees. But no state employees have been charged and those with first-hand knowledge of the events are not talking to the media. The Department of Public Safety objected to an Observer request for records about probes of Miller employees because “[t]he Department is conducting an investigation involving employees” of that agency.

After previous ethics and public integrity scandals, Miller always jumped right back into the saddle, as befitting an aging but undaunted rodeo cowboy. Yet the hemp scandal has left him with an ongoing investigation of his department—as well as a uniquely qualified and outspoken Democratic challenger.

Susan Hays is a lobbyist (and former board member of the Texas Observer) who helped her clients shape Texas’ 2019 legalization of hemp and its cannabidiol byproduct—CBD oil. Having previously helped young Texas women obtain abortions through the nonprofit Jane’s Due Process, Hays is not politically naïve.

Nonetheless, she told the Observer that she was outraged by the rumors she heard in late 2019 that people were being shaken down for hemp licenses. Hays said that spurred her to challenge Miller.

“It really pisses me off to see people misuse their office,” she said. “They are scamming people … who can’t afford to be scammed.” Hays concedes that Miller’s ties to the criminal charges against Smith are “fuzzy.”

But she says that the commissioner’s failure to quickly halt the abuses “suggests that he was getting a piece.”

In what could be Miller’s final payment to his longtime consultant, Miller campaign treasurer and legendary rocker Ted Nugent reported that the campaign paid Todd Smith a $15,000 “Consulting Expense” on January 5, 2022—two weeks before he was indicted.

Smith has put his own spin on that $15,000. Instead of consulting income that Smith’s wife might claim part of, Smith assured the court overseeing his divorce case that this $15,000 “Consulting Expense” actually was a repayable loan.

Nugent did not return calls about that payment.