Archaeologists think they may have found one of the largest prehistoric hunter-gatherer cemeteries in northern Europe just a hair south of the Arctic Circle. But the one important thing missing from the 6,500-year-old site in Finland is any evidence of human skeletons.

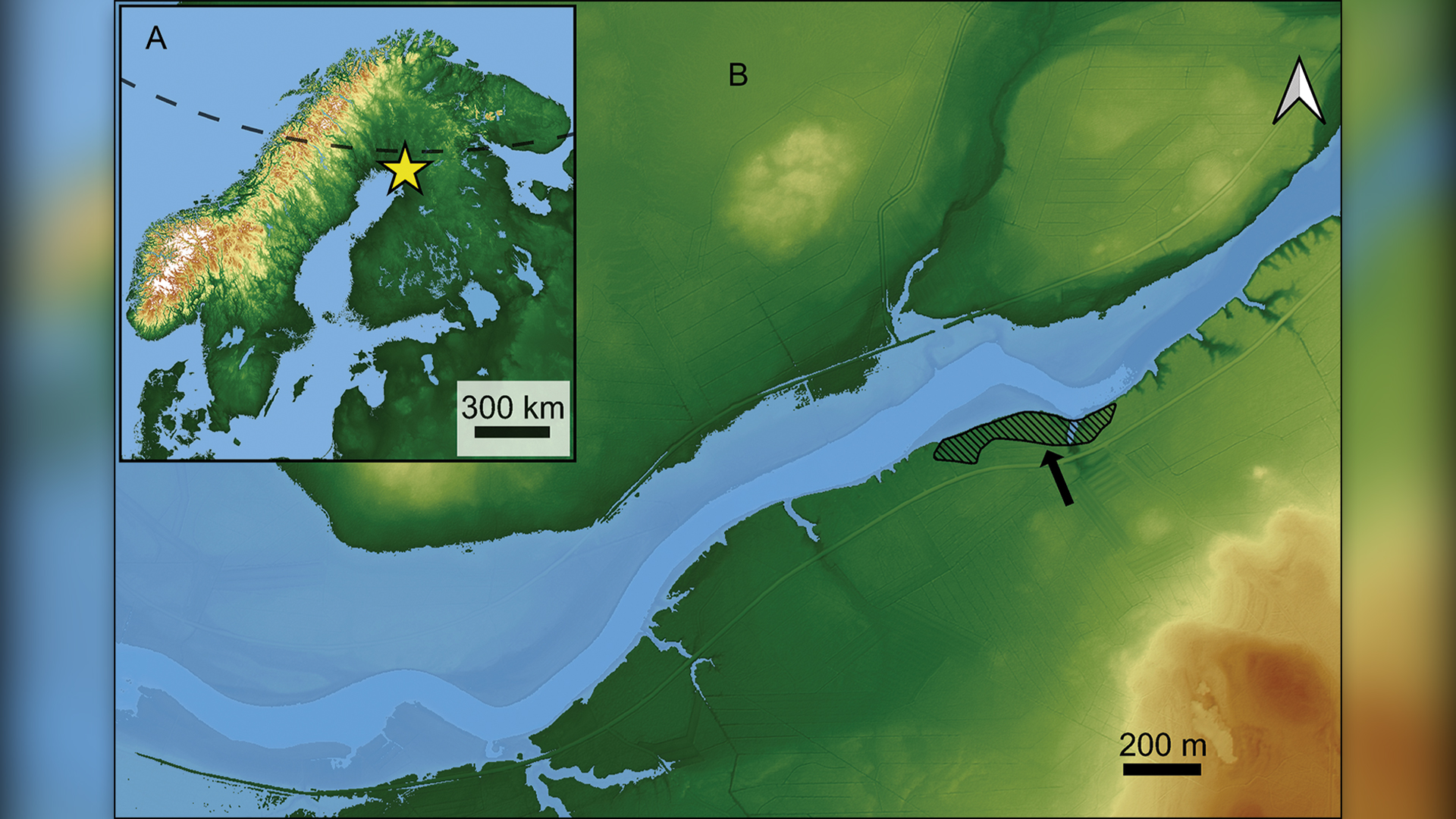

In 1959, local workers stumbled on stone tools in Simo, Finland, which is near the northern edge of the Baltic Sea just 50 miles (80 kilometers) south of the Arctic Circle. The archaeological site, called Tainiaro, was partially excavated in the 1980s, revealing thousands of artifacts, including animal bones, stone tools and pottery.

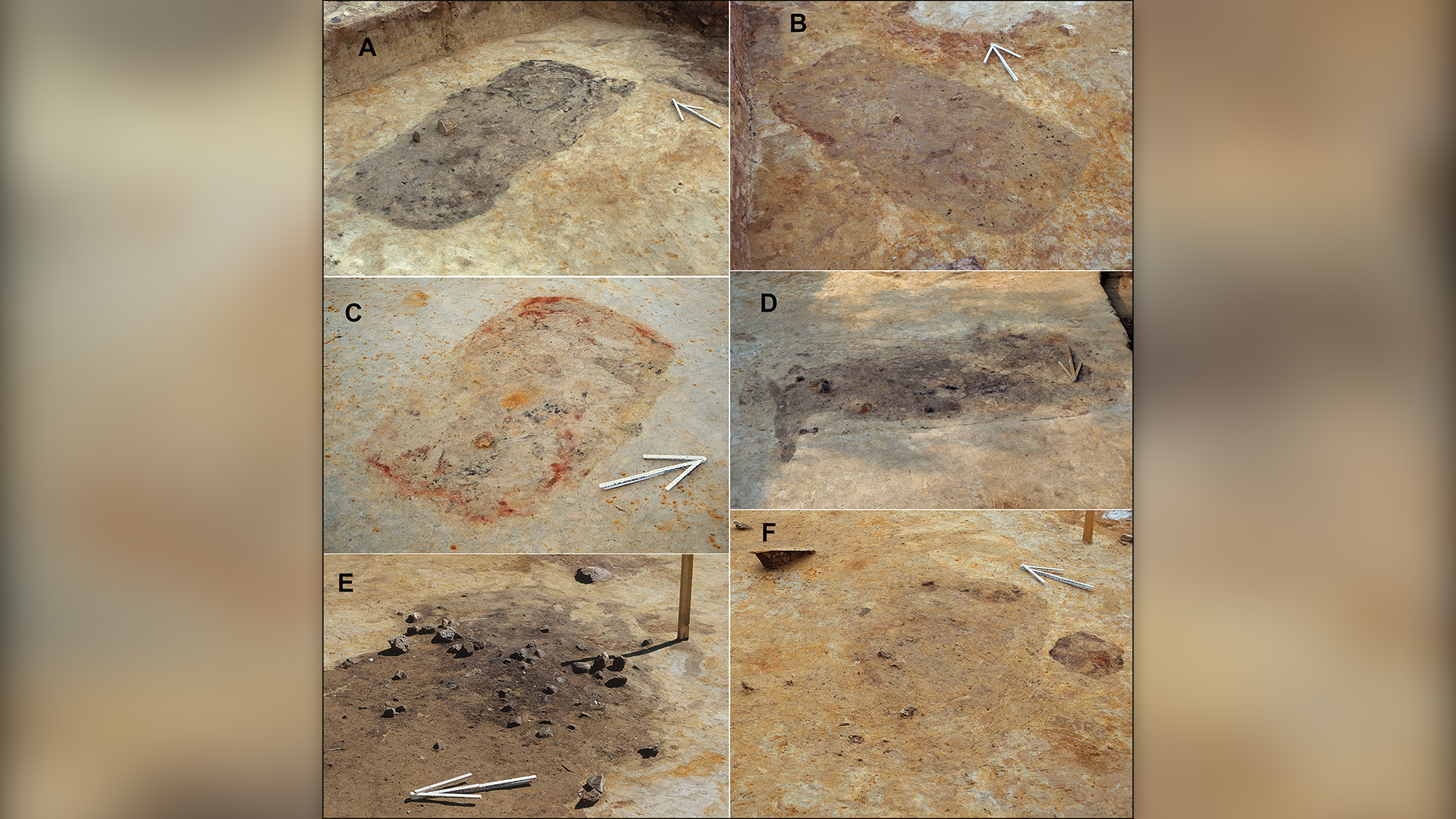

Archaeologists also noticed 127 possible pits of various sizes that have since been filled in with sediment. Some contained evidence of burning, and some had traces of red ochre, a natural pigment from iron that is a key characteristic of many Stone Age burials. Without evidence of skeletons, which decay quickly in this region's acidic soil, however, the identification of Tainiaro as a cemetery was never proved.

But after reanalyzing old records and undertaking new fieldwork, a team of researchers is proposing that Tainiaro was most likely a large cemetery dating back to the fifth millennium B.C., making it the northernmost Stone Age cemetery ever found. They published their findings Friday (Dec. 1) in the journal Antiquity.

For most of prehistory, this area of the world was occupied by people practicing a mainly foraging lifestyle as hunters, gatherers and fishers. Archaeologists found thousands of burnt animal bones at Tainiaro; most were from seals, but some came from beaver, salmon and reindeer, hinting at the variety of meat in the Stone Age diet and a probable domestic occupation of the site.

Related: Vast cemetery of Bronze Age burial mounds unearthed near Stonehenge

But initially, archaeologists were unsure if the pit features were hearths, graves or a mix of both. To clarify the nature of the 127 pits, the team, led by Aki Hakonen, an archaeologist at the University of Oulu in Finland, compared the pits' sizes and contents to those of hundreds of Stone Age graves across 14 cemeteries. They determined that at least 44 of the pits were likely to have contained human burials; the rounded-edged rectangular shapes of the pits, coupled with traces of red ochre and an occasional artifact, suggest a high probability that the pits were indeed graves.

"Tainiaro should, in our opinion, be considered to be a cemetery site," the authors wrote, "even though no skeletal material has survived at Tainiaro."

Based on the shapes of burial pits at other sites, the deceased at Tainiaro may have been buried on their backs or on their sides, with their knees bent, Hakonen said. "There would have been furs," he told Live Science in an email, and "the deceased could have been wrapped in [seal] skins." Food, grave goods and red ochre also could have been mixed into the grave or the fill dirt, Hakonen noted.

Ulla Moilanen, an archaeologist at the University of Turku in Finland who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that the authors' interpretations of Tainiaro are convincing. "Sometimes, it is difficult to say what kind of features can be interpreted as graves," she said, but "this paper provides excellent tools for studying poorly preserved material and is a very good starting point to study this and other similar sites more carefully."

"This study is much welcomed," Marja Ahola, an archaeologist at the University of Oulu, who was not involved in the present study, told Live Science in an email. Hakonen and colleagues can use the information they learned in this study to "bring forth important new insights into Stone Age funerary practices in the subarctic north of the Baltic Sea," Ahola said.

Only one-fifth of Tainiaro has been excavated, so the total number of graves could be higher — possibly more than 200. But the team is still testing whether ground-penetrating radar, which uses radar pulses to detect underground anomalies, could be helpful, because "no one wants to destroy the whole site," Hakonen said.

There is even a chance, according to Hakonen, that future work may reveal human skeletons, particularly if a grave was covered in red ochre, as it can preserve organic remains.

"If we manage new excavations at the site," Hakonen said, "we will also test whether ancient DNA could survive in the soil itself. But I wouldn't get my hopes up."