Ever since the American Dialect Society selected a Word of the Year at its conference in 1990, over half a dozen English dictionaries have anointed an annual word or phrase that’s meant to encapsulate the zeitgeist of the prior year.

In 2003, the publisher of the Merriam-Webster Dictionary began bestowing a crown. On Dec. 9, 2024, it selected “polarization” as its word of the year, which joins a list of 2024 winners from other dictionaries that includes “brat,” “manifest,” “demure,” “brain rot” and “enshittification.”

The terms that are honored are selected in a variety of ways. For example, this year the editors of the Oxford dictionaries allowed the public to cast votes for their favorite from a short list of candidates. Brain rot emerged victorious.

Other publishers rely on the acumen of their editors, augmented by measures of popularity such as the number of online searches for a particular term.

Given the steep decline in the sale of printed reference works, these yearly announcements raise the visibility of the publisher’s wares. But their choices also offer a window into the spirit of the times.

As a cognitive scientist who studies language and communication, I saw, in this year’s batch of winners, the myriad ways digital life is influencing English language and culture.

Hits and misses

This isn’t the only year in which nearly all the winners fell under a single thematic umbrella. In 2020, epidemic-related terminology – Covid, lockdown, pandemic and quarantine – surged to the fore.

Usually, however, there’s more of a mix, with some selections more prescient and useful than others. In 2005, for example, the New Oxford American Dictionary chose “podcast” – right before the programming format exploded in popularity.

More commonly, the celebrated neologisms don’t age well.

In 2008, the New Oxford American Dictionary selected hypermiling, or driving to maximize fuel efficiency. Permacrisis – an ongoing emergency – got the nod from the Collins Dictionary editors in 2022.

Neither term gets much use in 2024.

Manifesting brain rot

I can already anticipate one of this year’s selections – “brat” – falling by the wayside.

Just before the 2024 U.S. election, Collins Dictionary chose brat as its word of the year. The publisher defined it as “characterized by a confident, independent, and hedonistic attitude.”

Not coincidentally, it was also the name of a chart-topping album released by Charli XCX in June 2024. In late July, the singer tweeted, “kamala IS brat,” signaling her support for the Democratic presidential candidate.

Of course, with Harris’ loss, brat has lost some of its luster.

Other 2024 words of the year also have social media to thank for their popularity.

In late November, Cambridge Dictionary settled on manifest as its word of the year, defining it as “to use methods such as visualization and affirmation to help you imagine achieving something you want.”

The term took off when singer Dua Lipa used it in an interview. But she seems to have picked up on the concept from self-help communities on TikTok.

Another word that clearly benefited from social media was “demure,” chosen in late November by Dictionary.com. Although the word dates to the 15th century, it went viral in a TikTok video posted by Jools Lebron in early August. In it, she described appropriate workplace behavior as “very demure, very mindful.”

The Macquarie Dictionary of Australian English settled on “enshittification” as its word in early December. Coined by Canadian-British writer Cory Doctorow in 2022, it refers to the gradual decline in functionality or usability of a specific platform or service — something that Google, TikTok, X and dating app users can attest to.

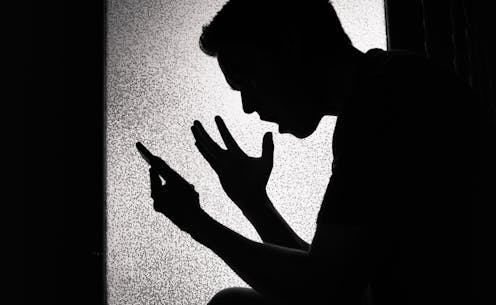

The Oxford dictionary pick for 2024 — “brain rot” — encapsulates the mind-numbing effects of excessive social media use.

The dictionary maker defined its word of the year as a “supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual state, especially viewed as a result of overconsumption of material (now particularly online content) considered to be trivial or unchallenging.”

Brain rot, however, isn’t a new concept. In the concluding section of “Walden,” Henry David Thoreau complained that “brain rot” prevailed “widely and fatally.”

Digital knives out

Merriam-Webster landed on “polarization” for its Word of the Year. The dictionary maker defined the term as “division into two sharply distinct opposites; especially, a state in which the opinions, beliefs, or interests of a group or society no longer range along a continuum but become concentrated at opposing extremes.”

In the U.S., political polarization has a number of causes, ranging from gerrymandering to in-group biases.

But social media undoubtedly plays a big role. A 2021 review by the Brookings Institution pointed to “the relationship between tech platforms and the kind of extreme polarization that can lead to the erosion of democratic values and partisan violence.” And journalist Max Fisher has reported on the ways in which the algorithms deployed by these social media platforms “steer users toward outrage” – an observation that experimental studies of the phenomenon have supported.

Despite the polarization of political and social life, the dictionaries, at the very least, have arrived at a consensus: The tech giants are shaping our lives and our language, for better or for worse.

Roger J. Kreuz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.