It’s tough being an environment minister. If you’re a Coalition minister, any holding up of a new mine, land-clearing or gas project, no matter how catastrophic, is evidence to colleagues you’re a sopping-wet dill captured by your department and an enemy of free enterprise. Unless it’s a renewables project, in which case you’re expected to find the mildest pretext to block it.

For Labor environment ministers, any approval of anything is evidence of a wholesale betrayal both of your personal beliefs and what few green credentials the party has.

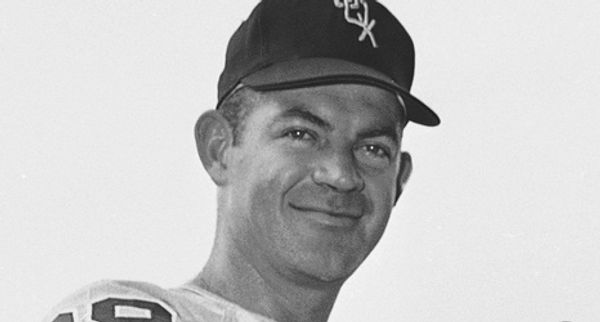

Peter Garrett got it worst in 2009 when he approved a uranium mine, with the former (and future) Oils frontman, Nuclear Disarmament Party candidate and Australian Conservation Foundation president savaged for betraying his principles.

Now it’s Tanya Plibersek’s turn. Garrett didn’t have to endure abuse on social media, which was in its infancy in 2009, but Plibersek has copped plenty from Twitter lefties for approving new coalmines or extensions to existing ones, with cheers for environmental groups taking her to court to overturn her decisions. The Greens and groups like the Australia Institute have joined in criticising her. At least now it’s clear why people thought Anthony Albanese giving Plibersek environment was a real poisoned chalice.

Problem is, nearly all of the criticism, derision and abuse directed at Plibersek is unjustified.

Her decision to approve the Isaac River coalmine in Queensland in May — dutifully written up in Guardian Australia as enraging climate campaigners and the Australia Institute — related to a metallurgical, not thermal, coalmine. Bizarrely, Guardian Australia notes that the mine produces coking coal but then, straight-faced, reports it as though it’s a new fossil fuel project.

Steelmaking using hydrogen is slowly growing, but is still far more expensive than steel made with metallurgical coal, is still at the pilot project stage, and requires massive investment in new and retrofitted blast furnaces. We’re stuck with metallurgical coal for many years yet even if we dramatically scale up hydrogen-based steelmaking. Who’s for ditching steel, or paying a lot more for it? Anyone?

The conflation of metallurgical and thermal coal is not a one-off — the Australia Institute has complained about the expansion of the Vulcan coal project. Again, it’s metallurgical coal.

The bigger problem with attacking Plibersek — like the attacks on Garrett — is the assumption that, in making a decision under legislation, a minister can simply decide whatever they personally like, without consideration for the requirements and considerations Parliament imposes on the decision via the relevant act.

And there’s no climate “trigger” in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (EPBC) with which a minister can block projects up for consideration. Block a project on the basis of its climate impact and a court will very quickly overturn the decision, regardless of how ardently a minister might feel on the issue.

Climate activists are — rightly — all for using courts to challenge ministerial decisions to approve projects. The Coalition, fossil fuel advocates and mining interests might term it “lawfare”, but it’s an entirely legitimate strategy. We live in a society with the rule of law, and courts and tribunals can review most ministerial decisions. But they’re not the only side that gets to challenge decisions.

A climate “trigger” could be added to the EPBC. That’s been the Greens’ position for a long time, but it was one rejected in the Samuel review of the EPBC under the previous government. Samuel and co instead recommended project proponents be required to detail the climate impacts of projects, but dealing with that impact should remain the subject of separate policy tools.

Whether the EPBC is the best vehicle for addressing climate impacts, or whether a standalone mechanism (like Labor’s safeguard mechanism, or a carbon price) is better is a live debate. The real problem is Labor’s reluctance to take climate change seriously.

In its response to the Samuel review last December, Labor proposed to set up an Environment Protection Agency to administer the EPBC, though the environment minister will still have a “call-in” power to override that process. There’ll be no climate trigger added to the legislation, merely a requirement that project proponents estimate their scope one and scope two emissions.

Scope three emissions — the emissions downstream users produce with the product — are excluded from that requirement, in line with Labor’s pigheaded insistence that it’s not Australia’s problem what other countries do with our carbon exports.

Labor is slightly more serious about climate change than the Coalition. But it still takes big donations from fossil fuel interests, it still supports more fossil fuel exports, its MPs and ministers still know they can get lucrative post-political gigs with resource companies, and its key unions still oppose real climate action. Under Labor, Australia is ramping up its fossil fuel exports. The state remains captured by fossil fuel interests.

But does that mean Plibersek should join her critics in a fantasy world where ministers can wield power based on personal beliefs without considering the consequences? Or should she obey the law?