In her latest book, Australia’s Great Depression, Joan Beaumont offers a deeply conservative history animated by the neoliberal spirit of our age.

In many ways a sequel to Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War (2014), Beaumont’s continuing national saga tells the story of a “resilient nation”, a people whose personal values of “stoicism, independence, self-reliance and personal responsibility” defined their response to the worst economic crisis of the 20th century.

Review: Australia’s Great Depression – Joan Beaumont (Allen & Unwin).

Although more than a third of workers were unemployed by 1932 and many more were immiserated, although thousands of businesses were bankrupted, homes were lost and families separated, the “narrative of disaster that has dominated popular memory” needs to be “complemented”, in Beaumont’s view, by attention to people’s “capacity for resilience”.

The architects of Jobseeker might find reassurance here. The theory of “resilience” – originally a concept developed in biological sciences, borrowed by psychologists, and since critiqued as “embedded neoliberalism” – provides Beaumont’s book with its conceptual framework and historical narrative. Australia’s Great Depression tells the story of the impact of global economic forces on hapless communities and individuals. “Their endurance and survival,” Beaumont writes, “provide one of the most impressive narratives of resilience in the nation’s history.”

The “agency” displayed by community organisations also characterised the “strategies of self-help” adopted by families – with “the tireless maternal figure at the core”. Noting that “starvation did not stalk the streets of Depression Australia”, Beaumont draws heavily on David Potts’ earlier controversial history The Myth of the Great Depression (2006) concerning the “positive culture of poverty” to conclude that people “knew how to value simpler things”.

Read more: The Australian history boom has busted, but there's hope it may boom again

Political mobilisations

Beaumont is interested in family and community survival strategies, but not so much in political mobilisations animated by visions of radical change. She provides a detailed account of party politics – the warring of factions and toppling of leaders, from the 1920s into the 1930s, at state and federal levels – but the visions of a different world that sustained Aboriginal, feminist and labour movements and led to real changes in social policy are marginal to this history.

Indeed, “women”, the homeless, men forced “on the track”, Aborigines and migrants are all lumped into one section called “On the Margins” – part eight of a very long ten-part book. But as historians since E.H. Carr, at least, have pointed out, historical subjects only become “marginal” – or invisible – when historians make them so.

Beaumont’s lack of interest in feminist political mobilisation in response to the experience of the Great Depression is especially puzzling. The 1930s saw an upsurge in women’s political activism and a transformational shift away from earlier forms of maternalist politics towards a demand for equal pay and opportunity.

The oppressive experience of motherhood during the Depression, which led to an increase in abortions and maternal mortality and a decline in the birthrate – together with the relentless attacks on women in paid work – led to new demands for women’s economic equality.

“Women’s right to work,” proclaimed Victoria’s Equal Status Committee in 1935,

rests not on the number of her dependants, nor on the fact that she does or does not compete with men, but in the absolute right of a free human being, a taxpayer and a voter to economic independence.

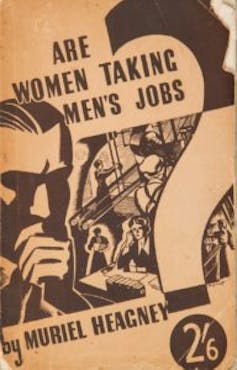

A key figure in this transition was the great labour feminist Muriel Heagney, whose influential book Are Women Taking Men’s Jobs? (1935) shaped the resurgence of the equal pay campaign in the 1930s and the formation of the Council of Action for Equal Pay in 1937. In the 565 pages of Australia’s Great Depression, Heagney barely rates a mention, and then only in the context of community relief funds.

Other key feminist figures are simply absent. Founder of the leading organisation the United Associations of Women (UA) Jessie Street, prominent broadcaster Linda Littlejohn, birth-control advocate Ruby Rich, fierce Aboriginal rights campaigner Mary Bennett, and the five UA candidates who stood in the New South Wales 1932 election are all missing from this history.

Similarly, Aboriginal activists Pearl Gibbs and Margaret Tucker are nowhere to be found, not even “on the margins” or at the Day of Mourning in Sydney in 1938, which they helped organise alongside the men.

Demands for radical change by angry women don’t fit so easily into narrative frameworks of endurance and stoicism. In Beaumont’s history, the story of resilience trumps the power of resistance.

Read more: Distance, dispassion and the remaking of Australian History

A transnational economic history

Global economic forces and the legacy of World War I shape Australia’s Great Depression. Beaumont’s strength is in economic history. Her account of the causes and duration of the Depression is based on wide reading. It is a marvel of synthesis, rendered more accessible by an extensive “Glossary of Terms” (53 in all, including “Bretton Woods”, “gold standard” and “loan conversion”).

It is something of an irony however that, for all Beaumont’s insistence that hers is a “national history”, its important dynamics are transnational. Indeed, the book might have been subtitled “A Transnational History”.

Part One deals with the effects of the Great War:

In every sense … the experience of the war framed the way that Australians understood and endured the later economic crisis.

Generous repatriation benefits – including the vast scheme of soldier settlement – added substantially to Australia’s burden of war debt. The promotion of the Anzac legend

served the function so critical to societal and personal resilience of investing the huge losses of World War I … with meaning.

Yet the paean to masculine heroism could also serve to intensify men’s sense of betrayal and humiliation when the promises failed, as the letters of bitter soldier settlers eloquently attested.

Part Two of Australia’s Great Depression covers the 1920s and details the economic and political effects of the dramatic fall in international commodity prices and Australia’s fate as a “voracious borrower” on British and US financial markets. It also introduces the key figure of English banker Otto Niemeyer, “who had the power to dictate a bitter deflationary medicine”. Beaumont quotes Niemeyer on Australia’s irresponsibility, tellingly casting the nation as female and in need of chastisement:

As Australia has borrowed abroad something like £200,000,000 since the date of the war loans, and has always represented her prospects and conditions in glowing terms on those occasions, it is quite ridiculous of her to suggest there is any reason why she should not pay a pittance for her prior war debts. This is an odd country full of odd people and even odder theories.

It was Labor Prime Minister James Scullin’s bad luck to come to office in 1929 as the New York Stock Exchange crashed, presaging “the implosion of the international economic order on which Australian recovery depended”.

Niemeyer arrived in mid-1930 convinced that bitter medicine needed to be administered. He was certain that a profligate country was living beyond its means. He met with Scullin, whom he regarded as “a very decent little man” but out of his depth. He also met with the commonwealth and state treasurers.

The subsequent Melbourne Agreement enshrined his recommendations, but led to immediate political division and bitter acrimony. Labor and non-Labor states differed in their responses. In New South Wales, Labor’s Jack Lang, promised to defend the standard of living, guarantee wheat prices and fund public works. He triumphed in the state election in October 1930, but two years later he was gone, dismissed by Governor Philip Game.

Humiliation

The year 1930 saw a peak in male suicides. Unemployment peaked in 1932. Men seemed to suffer more than women: “the men seemed to sag … They looked more beaten than the women”, observed one contemporary.

Though masculine “humiliation” is a constant theme of Beaumont’s story – and her photograph captions – the construct of “masculinity” is notably absent from her analysis and the index. This is in sharp contrast with the histories of the Depression by the late Stuart Macintyre, for example, for whom “gender” and “labour” were key dynamics.

Arguably, masculine humiliation was more likely to lead to demands for political change, rather than reconciliation to the status quo. Indeed “masculinism”, one correspondent argued in the Sydney Morning Herald, would be Australia’s “only salvation”. Under “feminism’s shameless banner”, he proclaimed, women were stealing men’s jobs.

Beaumont attributes some of the “protest and grievance” to what she – ever the academic historian – calls “grant envy”. Complaints also focussed on the filthy camps, the appalling conditions in which men were expected to travel and undertake “relief work”, and the introduction of work for the dole. “Slave Labour for Coolie Wages” was denounced by the Communist-led Unemployed Workers’ Movement, which organised many of the protests, including against evictions.

The main value of the men’s protest was, according to Beaumont, that it gave them a sense of “agency and a voice”. Their resilience meant that they still had the ability to fight and organise.

But insisting on the story of resilience, Beaumont misses the larger significance and consequence of men’s political mobilisations. The degradation of men’s unemployment and casual labour, of “susso” and the indignity of charity handouts, fuelled visions of a new kind of welfare state for men, that would enshrine full employment as the number one public policy goal, underpinned by the introduction of a federal unemployment benefit, conceived as a citizen’s right, free of shame or stigma.

As Macintyre noted, post-war reconstruction was in fact “post-Depression reconstruction”. In the words of Minister J.J. Dedman:

To the worker, it means steady employment, the opportunity to change his employment if he wishes, and a secure prospect unmarred by the fear of idleness and the dole.

Women imagined a new life freed from the burdens of excessive child bearing and the degradation of dependence. “I populated and I perished,” recalled one survivor of the Depression. Women dreaded the birth of more children. Fear of pregnancy deepened family discord. Children became unhappy witnesses of their parents’ misery. Many daughters determined never to follow in their mothers’ footsteps. Young women sought out birth control.

“I admit to being selfish,” said one, “but there are no medals given out for unselfishness.”

The Council of Action for Equal Pay was formed in 1937. Women would first benefit from equal rates during World War II, when the Women’s Employment Board regulated the pay and conditions of women workers who entered men’s jobs. By the end of that decade, following submissions from women’s organisations, the Arbitration Court lifted the female rate from half the men’s rate – as prescribed by Justice Higgins in the Rural Workers case of 1912 – to 75% of the basic male rate.

In her Epilogue, Beaumont returns to her argument about national resilience. Democracy survived; there was no revolution. People

accommodated the humiliation of unemployment, the reduction in their standard of living.

But when we look closely, we can see that new visions of freedom were born in the experience of degradation and the knowledge of fear. In Depression dreaming, there was a new day dawning.

Marilyn Lake has received funding from the Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.