In their 2021 book The Dawn of Everything, anthropologist David Graeber and archaeologist David Wengrow argue that much of what we take as the basic contours of human history are fundamentally wrong. The basic story is that first humans were hunter-gatherers who lived in harmony, and then the advent of agriculture ushered in the concept of “civilization,” for both good and bad.

“Agriculture, they write, “did not mean the inception of private property, nor did it mark an irreversible step toward inequality. In fact, many of the first farming communities were relatively free of ranks and hierarchies.”

This might explain the industry’s continued romanticism, an urge to return to a time before everything got so complex. Farming has romantic qualities, equal parts self-reliance and escape from the world’s many troubles.

When Yasuhiro Wada was looking for a way to stand out in the crowded ‘90s gaming market, he thought of this romanticism. As he describes in a talk he gave at GDC in 2012, he was hooked on a game called Derby Stallion, which simulated raising racehorses. While playing, two ideas he had been thinking about — setting a game in a rural area and making it non-violent — clicked together. Just take Derby Stallion and move it onto a farm.

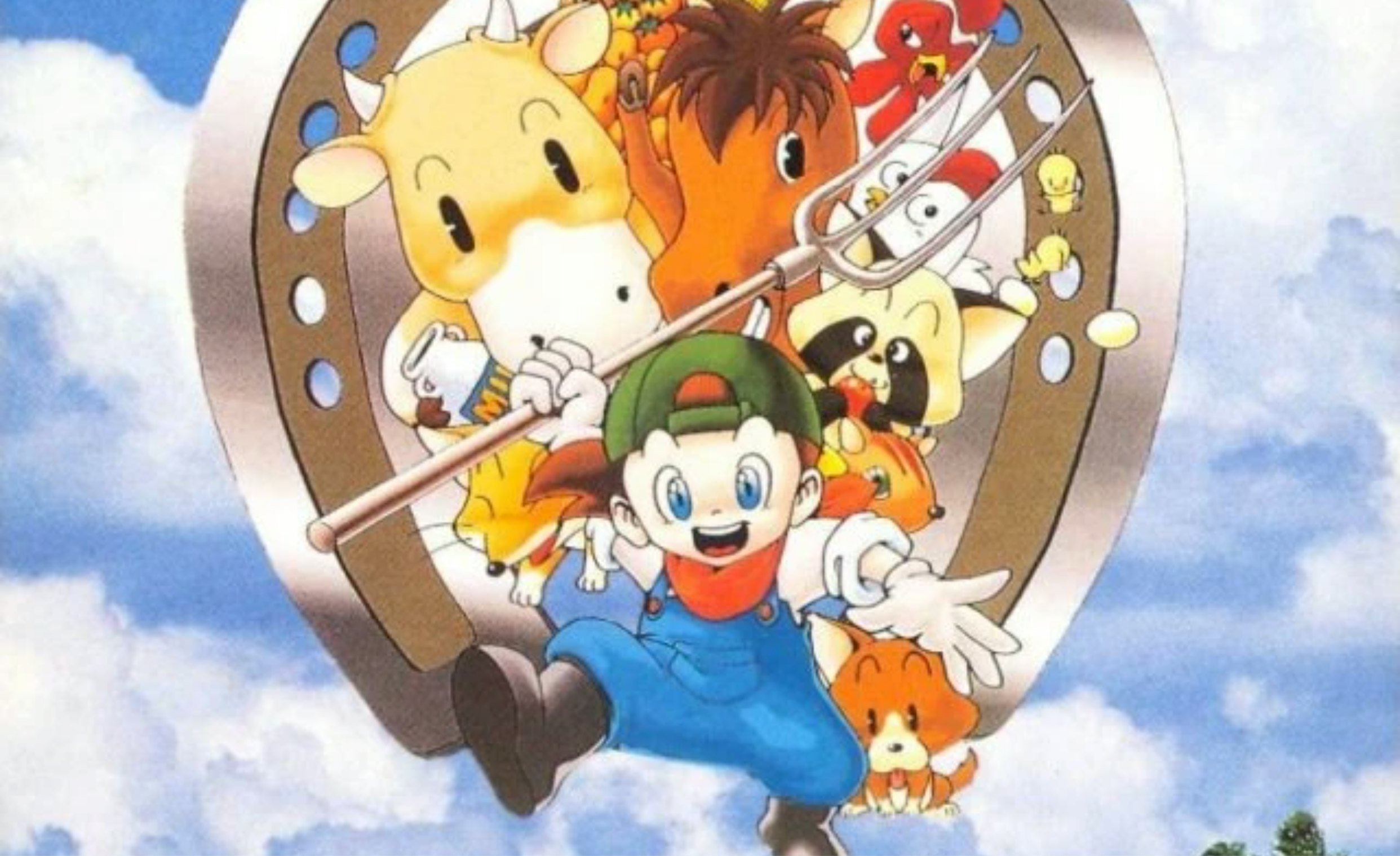

Eventually, this became the 1997 Super Nintendo game Harvest Moon, which is available right now if you’ve subscribed to Nintendo Switch Online. (Nope, you don’t need the Expansion Pack for this one.)

Harvest Moon starts off with a young man leaving his parents behind for life on his grandfather’s farm, which he received as an inheritance. The farm has been in disrepair for years, overrun with weeds and hurting for any growth. There’s a town to the left and mountains to the right, each filled with their own opportunities.

As he was making the game, Wada asked the question that many do when looking from the outside at work sims. “If you think about why people play games, it’s to enjoy something while not working…I thought, ‘why would I still want to go to work, or do these tasks, even when I’m playing a game?’ Would that be enjoyable? Does that sound fun?,” he recalled at GDC.

What would make Harvest Moon work, he thought, was pacing. Crucial to any work of entertainment, Wada felt, was a good mixture of pace. If something demands your attention constantly, it’s easy to get overwhelmed or tired. If it’s too glacial, it’s easy to get distracted. Having a mix of the two is what makes something enjoyable, be it a movie or a game.

That philosophy allowed Harvest Moon to set the template for farming games as we would come to know them. There’s a day/night cycle, crops, animals, freedom of choice in how you spend your day, townsfolk to talk with, and wives to woo. Harvest Moon didn’t set out to simulate the experience of going to work. Rather, it focused on the process of creation. Finding the right pacing for them would be what attracted players, Wada thought.

He was right. While having a walkthrough nearby might be handy for new players (some mechanics, like only getting a watering can after approaching a shop clerk behind her cash register, might not be entirely obvious), once the basics are understood, it’s easy to paint what you want on top of the Harvest Moon canvas. Ignore the farming all you want, and just hang out with the old guy fishing on the mountain! Make Ann your wife! Grow turnips! The possibilities aren’t endless, but they do promise constant variety.

There’s a way to play Harvest Moon to win. The industrious player will figure out quickly how to add in some useful machinery like sprinklers, raise animals, and get a wife quickly to help with food production. The romantic elements of Wada’s imagined countryside can be broken down into game mechanics. But Harvest Moon and its many, many sequels understood that even if a great vision can be gamed out, it cannot be defeated.

Harvest Moon invites players to a small utopia, arguing that it wouldn’t feel good if it wasn’t earned. Without it, we wouldn’t have the likes of Stardew Valley and Harvestella, or long-running series like Rune Factory and Animal Crossing. Sure, it’s a simple premise. But classic fun never gets old.