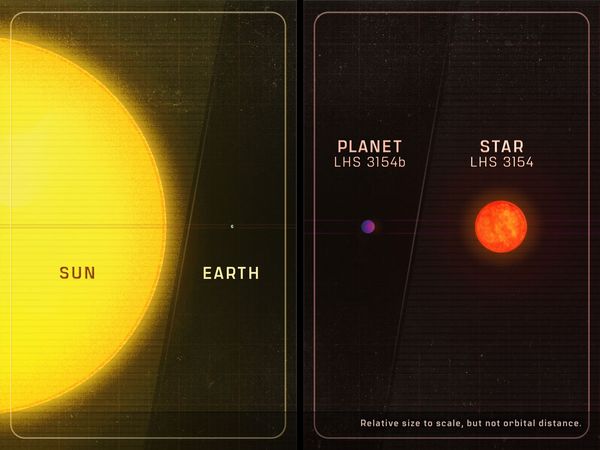

It's difficult to fathom how much bigger the Sun is than our little planet. Even though it's just an average-sized star, you could squeeze 1.3 million Earths inside it. But planets in other solar systems don't always have such a massive size difference, as detailed in an intriguing new report in the journal Science, which describes the discovery of a planet named LHS 3154b.

It orbits an M dwarf star called LHS 3154, from which it gets its name, but the planet itself is theoretically too big to orbit around its native star. Its very existence calls into question some fundamental tenets of how planets form that were taken for granted.

"The planet forming disk around a star is usually only a small fraction of the mass of the star and even less of that mass is tied up in solid materials," Dr. Suvrath Mahadevan, co-author of the paper and a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Pennsylvania State University, told Salon by email. "For a lower mass star we expect this disk also to be correspondingly less massive. For such a small mass star we don't expect that its disk should even have enough mass in solid particles to form this planet. This is why this discovery is so surprising."

Mahadevan added, "It's like finding an ostrich egg in a chicken-coop."

The discovery is particularly sweet for the scientists because of how it was made. The researchers utilized an astronomical spectrograph that was put together by a team of scientists led by Mahadevan. Known as the Habitable Zone Planet Finder (HPF), it is located at the Hobby-Eberly Telescope at the McDonald Observatory in Texas.

The purpose of the HPF is to monitor the coolest stars outside our solar system. In theory this is to discover those that may contain liquid water, which is an essential ingredient for life. Yet because the star LHS 3154 is an "ultracool" star, the HPF was able to detect it — and, consequently, the unusually massive planet that orbits it.

"HPF is the most precise instrument in the US at near-infrared wavelengths (where these stars emit most of their light) to detect the wobble of a star as the planet tugs on it," Mahadevan said. He added that the Hobby-Eberly Telescope is also advantageous for researchers because the data is accumulated by the astronomers at the telescope itself utilizing an observation queue. "This enables surveys that span many years and significant amounts of telescope time, which would be harder with other telescopes."

Indeed, the HPF has already carried its weight by discovering and confirming other new planets since it started being used. Yet this discovery is particularly significant and unique because it challenges long-held assumptions about planetary formation.

“Based on current survey work with the HPF and other instruments, an object like the one we discovered is likely extremely rare, so detecting it has been really exciting,” Megan Delamer, astronomy graduate student at Penn State and co-author on the paper, said in a statement. “Our current theories of planet formation have trouble accounting for what we’re seeing."

Reflecting on this astronomical accomplishment, Mahadevan expressed a similar thought to Salon, noting that the only reason scientists have discovered for the first time such a high mass planet orbiting such a low mass star is that scientists have developed better technology for studying the skies.

"Discoveries in astronomy are often driven by increased measurement precision and new technology enabling us to view the Universe in a different way," Mahadevan wrote to Salon. "While we built the HPF instrument to discover terrestrial planets, it has also led us to discover such rare objects."

In a statement about the discovery, Mahadevan emphasized that this discovery underscores "just how little we know about the universe,” adding that it's unexpected for a planet this heavy around such a low-mass star to exist. He further elaborated on how this is possible by comparing a planet orbiting a star to a campfire.

“The more the fire cools down, the closer you’ll need to get to that fire to stay warm,” Mahadevan said. “The same is true for planets. If the star is colder, then a planet will need to be closer to that star if it is going to be warm enough to contain liquid water. If a planet has a close enough orbit to its ultracool star, we can detect it by seeing a very subtle change in the color of the star’s spectra or light as it is tugged on by an orbiting planet.”