In May 2021, local art teacher Maria Llopis led a group of her female students in what she called a “silent protest” at the Picasso Museum in Barcelona. This involved walking around en masse in T-shirts bearing messages such as “Picasso, abuser of women” and “Picasso, Bluebeard” (the latter a comparison with the French fairytale character who murdered his wives).

Picasso was not guilty of uxoricide, of course, and no harm was done at the museum beyond raising the blood pressure of a few security guards. Llopis said she simply felt the need to protest against the lack of attention given to the artist’s historical mistreatment of women.

Her protest presaged a debate that will be had on a far larger scale this year. Was Picasso a misogynist? Moral purity isn’t a requirement for making art, but what level of impurity won’t we tolerate? Picasso died on 8 April 1973, aged 91, making 2023 the 50th anniversary of his passing. To honour the occasion, the French and Spanish governments have come together to organise a year-long programme of exhibitions and events: Picasso Celebration 1973-2023. It was launched officially at a press conference at Madrid’s Reina Sofia museum last autumn, where the King of Spain was among the speakers. (Funnily enough, His Majesty didn’t mention Picasso’s observation that “women are machines for suffering”).

More than 40 exhibitions are being staged, most of them in Spain and France, with others being held in the United States, Germany, Switzerland, Monaco, Romania and Belgium. Interestingly, no British institution is hosting a show – but more on that later.

A glance at the schedule suggests that the year ahead will, as the programme name suggests, mostly be celebratory. The exhibitions include Young Picasso in Paris at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, focusing on the artist’s epoch-making move to the French capital in his early twenties; Picasso. The Sacred and the Profane at the Thyssen-Bornemisza museum in Madrid, exploring his radical spins on traditional genres such as portraiture and still life; and Picasso. Artist and Model – Last Paintings at the Fondation Beyeler in Basel, featuring 10 standout canvases from his final years.

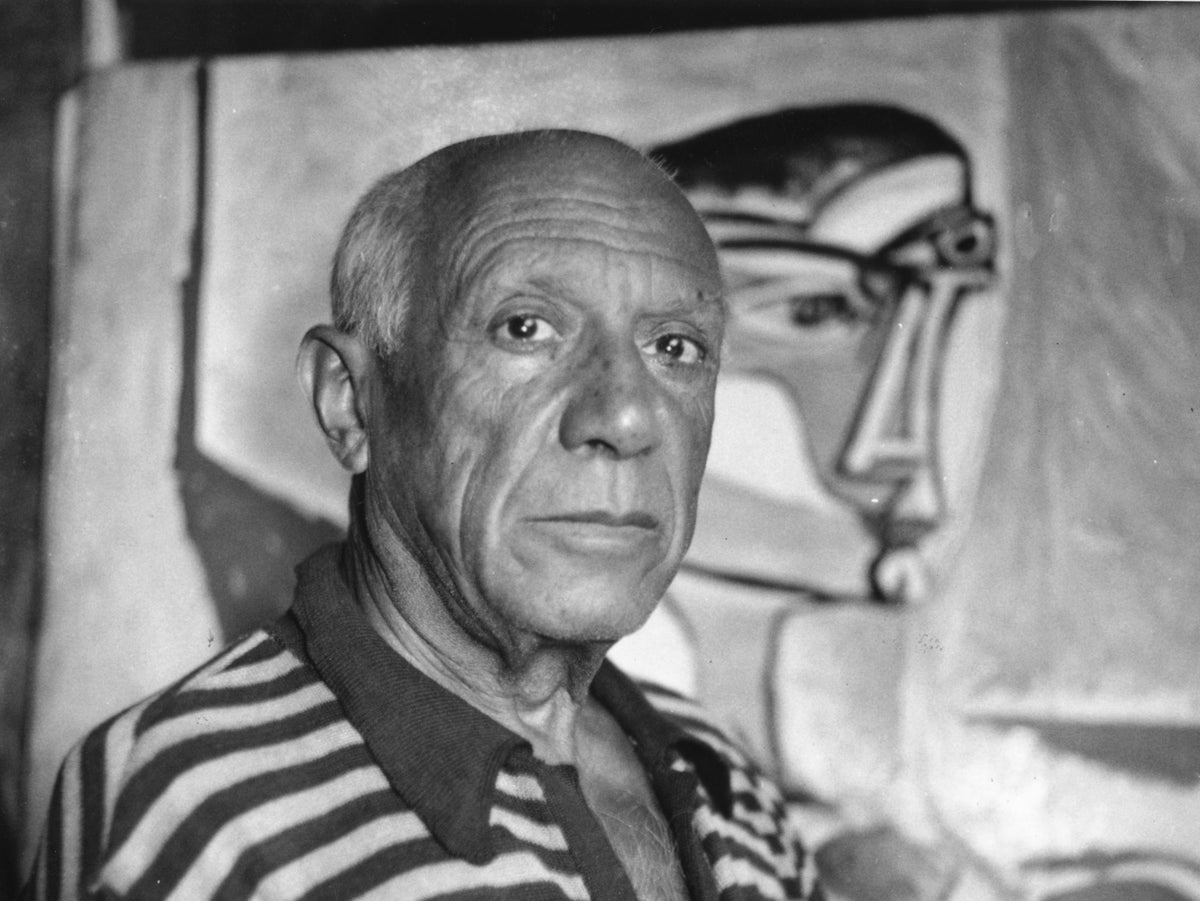

In short, the shows will offer a broad collective look at the many periods and triumphs of Picasso’s career. His creative genius is beyond dispute: here was a man who spent 70 years finding ever more radical ways of depicting the human figure. Those who attended the programme’s launch, however, will have heard some carefully chosen words. “If there’s an artist who defines the 20th century, who represents it with all its cruelty, violence, passion, excesses and contradictions, this is undoubtedly Pablo Picasso,” said Spain’s culture and sports minister, Miquel Iceta.

The French minister of culture, Rima Abdul Malak, in turn, said: “Let’s not hide our face. Today there are many debates around the reception of Picasso’s work, in particular from his relationship with women. To lead the younger generations towards his art, we must give them the keys to understanding his work [and] life, and open spaces of exchange.”

It’s as if the ministers’ plan – to borrow a phrase from rugby great Willie John McBride – was to get their retaliation in first. That is, to pre-empt any criticism that, in a post-#MeToo age, 2023’s programme amounts purely to adulation. Both ministers intimated that we shouldn’t judge a historical figure by contemporary values. Which is fair, up to a point. But certain actions are reprehensible whatever the era.

Let’s have a look at the artist’s rap sheet, and people can make up their own minds. Picasso was a serial philanderer, and, as his marriage to his first wife, Olga, deteriorated (and her mental health with it), he started a relationship with 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter. He was 45 – and swiftly initiated her in the ways of sadomasochistic sex.

Picasso was a serial philanderer, and, as his marriage to his first wife, Olga, deteriorated (and her mental health with it), he started a relationship with 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter. He was 45

A decade later, when Walter grew jealous of his latest lover, the photographer Dora Maar, Picasso told the pair to fight for his affections. Literally. In his studio, while he painted. Later in life, he reportedly described the scrap as “one of my choicest memories”. When Picasso left her, Maar had a nervous breakdown and received weeks’ worth of electric-shock treatments in a psychiatric hospital.

He used to make his next lover, Françoise Gilot, wake daily at dawn to light the stoves in his studio. Following their split, he refused to see their two children, after she published a tell-all memoir of their relationship, Life with Picasso (1964).

There have been occasional, unsubstantiated claims – many in Arianna Huffington’s book Picasso: Creator and Destroyer (1988) – that the Spaniard used physical violence against women. Huffington claimed, for example, that he had once put out a lit cigarette on Gilot’s cheek.

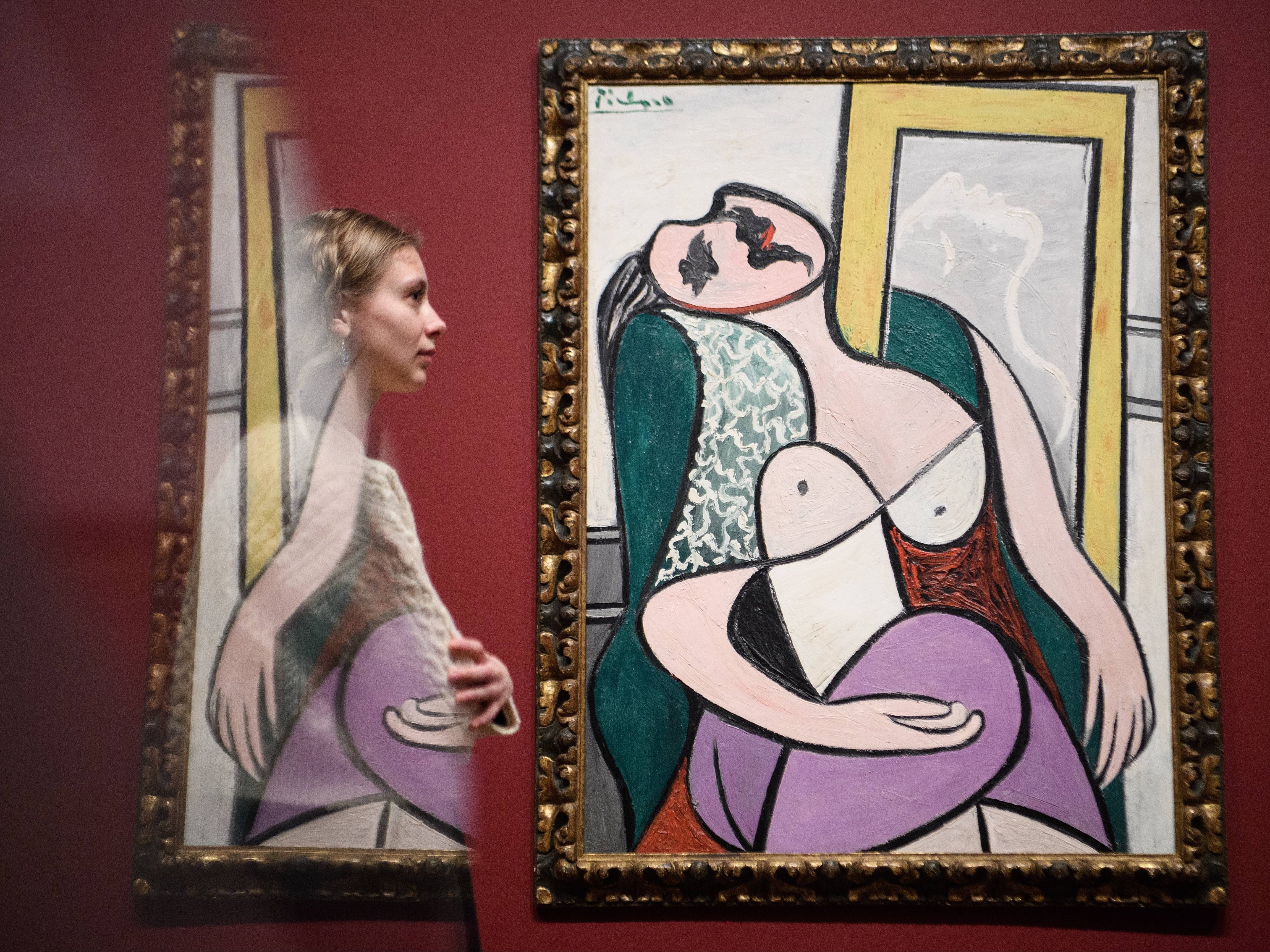

It must be stressed, however, that only psychological violence has been factually documented. Picasso’s savage depictions of certain lovers – such as 1929’s painting of Olga with a grotesquely deformed body, Large Nude in a Red Armchair – might be deemed further examples of this. According to the artist’s granddaughter, Marina Picasso, writing in her book Picasso, My Grandfather (2001), his treatment of partners followed a pattern: “He submitted them to his animal sexuality, tamed them, bewitched them, ingested them, and crushed them onto his canvas. After he had spent many nights extracting their essence, once they were bled dry, he would dispose of them.”

The exhibition Picasso and Feminism, opening at the Brooklyn Museum in June, will cover this ground. It’s set to be the most scathingly critical show of the year. Co-curated by the Australian comedian Hannah Gadsby, it will explore, we’re told, the “interconnected issues of misogyny, masculinity, creativity, and ‘genius’”.

This promises to cut to the core of the day’s entire debate about Picasso: does the pleasure of countless millions of art lovers justify the suffering of a handful of women at his hands? Related to that, does the trope of the solitary, male, creative maestro – so prevalent in Western cultural appreciation – not actually encourage misogyny?

Gadsby, a graduate in art history herself, made waves in 2018 with her stand-up show for Netflix, Nanette, which featured an almighty takedown of the artist. “I hate Picasso,” she stated, before discussing how horrid behaviour by male artists has long been indulged by a male-dominated society. “Thanks to art history,” she said, “I understand this world and my place in it. I don’t have one.”

Time will tell how condemnatory the year’s other curators will be. Fernande Olivier and Pablo Picasso, a recently closed exhibition at Montmartre Museum, set an interesting example. This gave the Spaniard equal billing with his early muse and fellow artist, Fernande Olivier, showing their work side by side. The aim was to make up a fraction for the decades in which Olivier’s art has been neglected, and she herself has been remembered as just a planet in Picasso’s universe.

A Dora Maar retrospective at Tate Modern in 2019-20 had the same intent. As Llopis put it on Instagram after her protest, “Picasso played the role of Bluebeard by devouring the creative power of each woman in his life.”

What to make, though, of the lack of British participation in Picasso Celebration 1973-2023? Is there some national boycott we’re not aware of? “No, no,” says Frances Morris, director of Tate Modern. “Anniversary years tend to be honeypots... and there’s a risk that, in the worldwide rush to get loans of an artist’s work, the quality of any show will be compromised.”

In other words, there was no appetite in this country to try to compete with what the French and Spanish were doing. There’s every chance Tate will stage a Picasso show in the coming years, though. “Income from exhibitions is a key part of a British museum’s business model,” Morris says. “The easiest way to attract visitors to exhibitions is [by showing] artists who are in the public consciousness, and Picasso is very high on that list.”

Tate Modern’s last show dedicated to the artist was Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy in 2018. It attracted 521,080 visitors, making it the third most popular exhibition ever to be held at any of Tate’s four galleries.

The market for Picasso’s work isn’t shabby either, with five of his paintings having sold at auction for more than $100m (£82m) – including the portrait of Walter, Femme Assise Près d’une Fenêtre (Marie-Thérèse), at Christie’s in 2021. Auction house press releases regularly speak of Picasso’s huge “brand recognition” globally, with ever-increasing interest in his work among collectors in Asia.

According to the latest Burns Halperin Report, a paper tracking equality in the art world, sales of Picasso’s work made more money at auction between 2008 and 2022 than the work of all female artists combined ($6.23bn versus $6.2bn).

Sales of Picasso’s work made more money at auction between 2008 and 2022 than the work of all female artists combined

And what of his influence on artists today? It’s fair to say that few of art’s current heavyweights laud Picasso in the way that their 1980s counterparts – such as Roy Lichtenstein, Louise Bourgeois, Robert Rauschenberg and Christo – did in this New York Times write-up of a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Modern Art.

Perhaps Picasso’s influence can be felt in a broad sense, though, in his multidisciplinary approach to art: he turned his hand freely to painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking, ceramics, theatre set design and more. The fashion designer Paul Smith discussed this in an interview with The Art Newspaper recently, ahead of a show he’s curating at the Musée Picasso-Paris.

“Picasso is relevant to any creative person working today,” Smith says. “He found anything interesting and… didn’t become cluttered with experience and history and education, but stayed open to new ways of thinking.”

One present-day artist who cites Picasso as a “big inspiration” is his thirtysomething compatriot Coco Dávez. She says she “understands” calls for him to be cancelled. For a new exhibition of hers at London’s Maddox Gallery – featuring paintings of famous duos in Dávez’s trademark style, without facial features – she was on the verge of dropping a picture of Picasso with his friend, Coco Chanel.

However, she says, she included it in the end as she decided “there must be a way of redeeming art without approving of its creator’s behaviour”.

The trouble is, with Picasso, his art has always been inextricably entwined with his life story. As he himself said, “My canvases ... are the pages of my diary.”

So where does that leave us? With Picasso being such a huge cultural figure, one suspects that any shift in his status will be gradual. The ostensibly minor case of Dávez’s portrait, though, is a reminder that the year ahead may have many unexpected twists.

The artist’s reputation seems more open to challenge than ever – even if, with the whole Picasso Celebration 1973-2023 jamboree planned, nobody can say he’s being cancelled. When the year is out, we should have a better idea what place Picasso, the greatest artist of the 20th century, has in the society of the 21st.

More information about Picasso Celebration 1973-2023, including exhibitions and events, can be found at celebracionpicasso.es