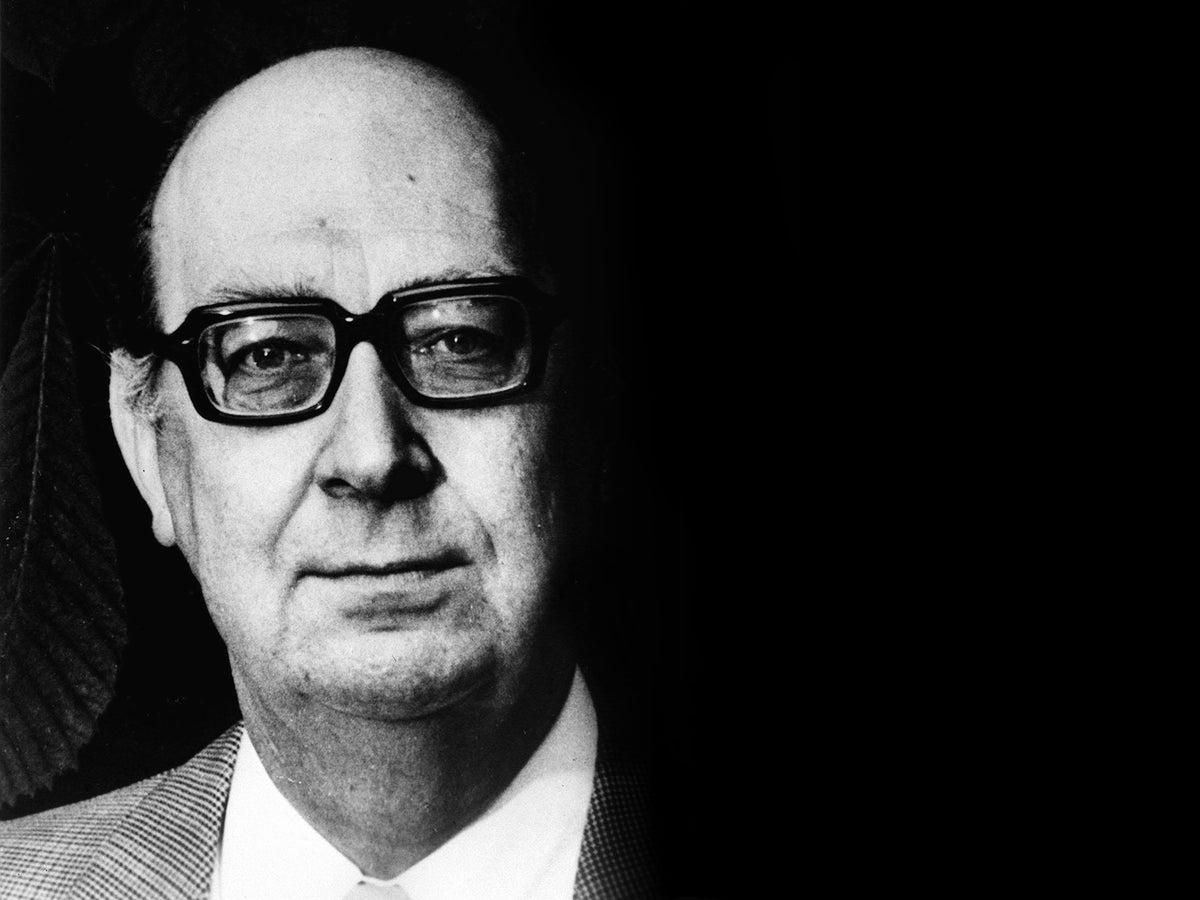

A few years ago, for a birthday treat, I went to Hull. I wanted to walk The Larkin Trail, a tour of various workaday locations that held some significance to the poet Philip Larkin. It took me to the Brynmor Jones Library at the University of Hull, where he was librarian for 30 years, and the nearby house on Newland Park where he lived until his death in 1985 at the age of 63. The trail ended a bus ride away in the village of Cottingham, at the Municipal Cemetery on Eppleworth Road. By the time I arrived the gates were locked, which is how I found myself scrambling over a low stone wall, drenched to the skin by the pouring Yorkshire rain, looking for a poet’s tombstone.

To me, Larkin is a writer worthy of sodden pilgrimage. Like generations of British school kids, I first read his poems in GCSE English class. I fell in love with “An Arundel Tomb” not because of its famous final words, “What will survive of us is love”, but for the morbid way he moderates that epigrammatic thought in the preceding lines, “to prove / Our almost-instinct almost true…” On his original manuscript draft, Larkin scrawled a cynical rejoinder to himself: “Love isn’t stronger than death just because statues hold hands for 600 years”.

Larkin wrote about mortality more plainly and clear-sightedly than any writer I’ve ever read. The finest example is “Aubade”, Larkin’s great poem about, “The sure extinction that we travel to / and shall be lost in always.” Completed in 1977, shortly after the death of his beloved mother and occasional muse Eva, “Aubade” was first published in the Times Literary Supplement that December.

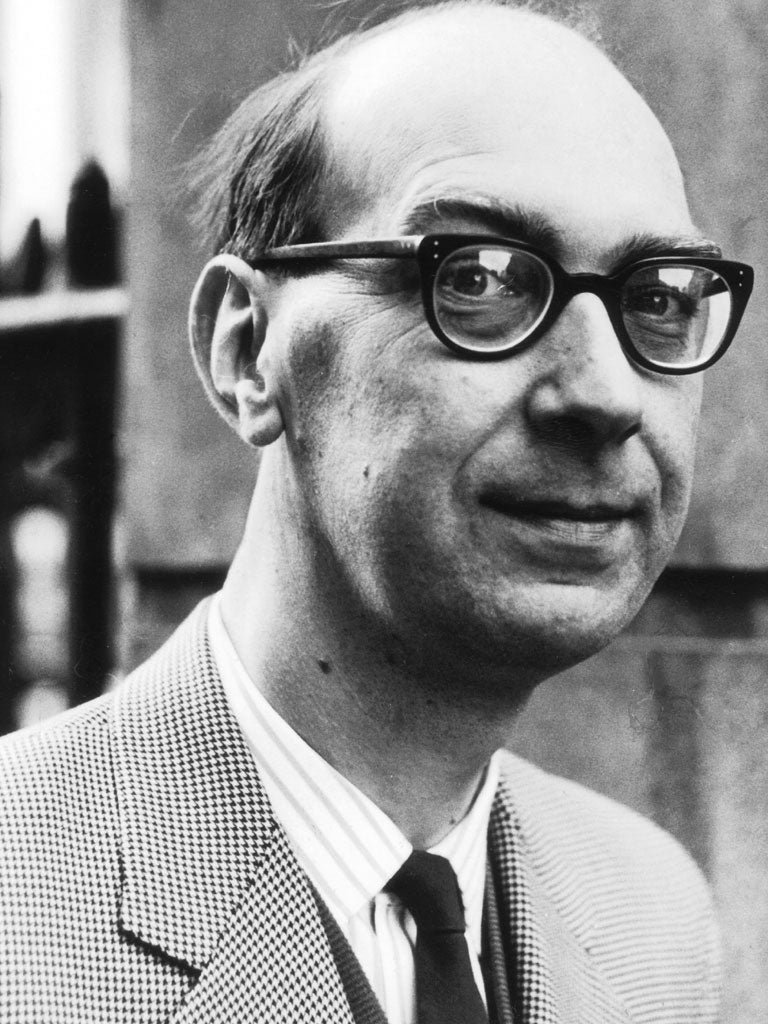

At the time, the poet Andrew Motion was also working at the university. “I remember seeing Philip a few weeks later, when the spring term began back at Hull, and saying that he’d ruined my Christmas for me in the best possible way!” Motion tells me from his book-lined office in Baltimore. “He was beaming. It’s a strange poem, though, in some respects. Even though that fear of death and the squaring up to it is absolutely central to his bones from the get-go, it’s so much less adorned. That gloomy iambic beat is similar to things that we’ve seen in earlier poems by him, but it’s also out there on its own as a candid statement of fearfulness.”

Motion, too, had first read Larkin at school, and applied for the job in Hull partly in the hope of catching sight of the reclusive poet. The pair became close friends after an awkward first encounter in 1976. “We were drinking beer at lunchtime, which was sort of routine back then,” Motion remembers. “He was 53 but seemed a great deal older. Overweight, balding, death-suited, watch chain, all those kinds of things. He asked me what my father did, and I told him he was a brewer. Philip was so pleased that I came from stock which produced something that people actually want, alcohol, rather than art, which they can take or leave. Soon after that he took a swig of beer which went down the wrong way. He was doing a good deal of coughing and spluttering, taking his glasses off, mopping his face. I was pounding him on the back. As social icebreakers go, it’s probably quite an effective one.”

Motion’s 1993 biography of Larkin, A Writer’s Life, didn’t shy away from the poet’s reactionary views and the racist language he used in some of his personal letters. “Those things make him a figure less easy to adopt, but it also made him an even more interesting poet, I think, because it allowed us to ask what the relationship is between the things that somebody says in their poems and the life that they lead,” says Motion. “It makes me feel that he spent really quite a lot of his time as a writer trying not to be Philip Larkin.”

Larkin was born in Coventry a century ago, on 9 August 1922. His father, Sydney, was a Nazi sympathiser who attended Nuremberg rallies during the Thirties. “That would take a lifetime to get over, wouldn’t it?” says Motion of Larkin, who wrote in “Aubade” that, “An only life can take so long to climb / Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never”. Arguably Larkin’s most famous poem also concerns his upbringing. “They f*** you up, your mum and dad,” he wrote in 1971’s “This Be The Verse”. “They may not mean to, but they do.”

At school, and later while studying English at university in Oxford, Larkin saw his discomfort around girls harden into cruelty and misogyny. Although the term wasn’t around at the time, I ask Motion whether it would be accurate to describe the young poet as an “incel”. “If that concept had existed I’m sure I would have wanted to talk about it in my book,” he replies. “It’s not inappropriate.”

Larkin took up the librarian position in Hull in 1955, the same year he published his breakthrough poetry collection The Less Deceived. He set out purposefully to lead a largely solitary life, partly inspired by the literary critic Cyril Connolly’s famous claim that: “There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.” When Larkin met Connolly at poet John Betjeman’s memorial service in 1984, he bounded across the lawn and shook him by the hand saying: “Sir, you made me.” However, Motion believes Larkin’s withdrawal from life was also tied up in his own blighted physiology. “He had a very strong sense of himself as in some way misshapen,” he explains. “He’s deaf. He can’t see very well. He was always complaining about things going wrong in his body. He has low self-esteem, and you can easily see how those things might curdle into a reluctance to spend much time around other people. He just wanted to hide himself away.”

I read the poems almost on every page thinking: ‘Yes, life is like that. That is my experience of being alive’— Andrew Motion

Despite Larkin’s well-earned reputation as a curmudgeon, Motion remembers him as a good friend who would ask sincerely how others were feeling. He was also, Motion says, “the funniest person I ever met, by a long way. Not just witty, though certainly that, but also with a very strong sense of the ludicrous in life.” It is not necessary, he points out, to agree with any of Larkin’s staunchly Conservative political or personal views in order to be touched by his work. “I’ve never voted as he voted. I don’t feel the same about women. I don’t feel the same about ‘abroad’,” he says. “You go through the whole panoply of prejudices that he has and think: I might have prejudices of my own, but they’re not these ones. And yet, I read the poems almost on every page thinking: ‘Yes, life is like that. That is my experience of being alive.’ It is a remarkable thing.”

The Less Deceived made Larkin’s name as a poet, and began to build his reputation as the laureate of the humdrum. In “Toads” he grumbles about having to work for a living: “Why should I let the toad work / Squat on my life?” He expressed this sentiment even more vividly in a brief verse sent to his long-suffering girlfriend Monica Jones: “Morning, noon and bloody night / Seven sodding days a week / I slave at filthy WORK, that might / Be done by any book-drunk freak / This goes on until I kick the bucket / F*** IT F*** IT F*** IT F*** IT.”

Larkin’s next collection The Whitsun Weddings, which includes “An Arundel Tomb”, made him nationally famous in 1964. A decade later he published High Windows, a collection that turned him from a well-known writer into something of a national monument, the country’s poetic grouchy hermit. It features some of his most celebrated work, including the transcendent title poem, “This Be The Verse” and “Annus Mirabilis”, which managed to capture the national imagination with its wry opening: “Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three / (which was rather late for me) – / Between the end of the ‘Chatterley’ ban / And the Beatles’ first LP.”

Motion argues that more than any other poet, Larkin’s most memorable lines have embedded themselves in the British psyche. “His reputation might be more complicated now than it was at the end of his life, but he’s entered the national bloodstream in a quite startling way,” he says. “I think more lines by Philip are in the national bloodstream than by TS Eliot, and that’s saying something.”

Earlier this year, GCSE exam board OCR announced that Larkin would be removed from their English curriculum, along with the First World War poet Wilfred Owen, in an effort to offer more diversity. Nadhim Zahawi MP, then the education secretary, described the decision as “cultural vandalism”. Motion, too, believes that Larkin deserves a continued place in the classroom. “He should be there because he tells the truth about human experience, regardless of our background, skin colour, age, you name it, and he says it in a beautiful and memorable way with a great deal of skill that is worth looking at for its own sake” he says. “There’s also a great deal of emotional depth charging, which opens us up as individuals as we read.”

That’s not to say that the English curriculum isn’t in need of new voices. “Why can’t we have both?” asks Motion. “Why can’t we have the new kids on the block as well as these old guys. Surely then teachers and students themselves have a richer experience of reading, and surely that meets the charge one might make against these sorts of expulsions that they put literature in the service of some sort of social idea rather than being an end in itself. It is an end in itself, for a multitude of reasons. One of them being that almost all other sorts of discourse in life exist for a purpose. Though it sounds paradoxical to say, one of the most profound pleasures and significant things about literature is that it makes nothing happen.”

When I first read “Aubade”, it stopped me in my tracks. I have returned to it countless times since, drawn back to its profound ability to put the deepest terror of the human condition into words “plain as a wardrobe”. “We need moments in our life when the relationship between cause and effect is interrupted, and we just dwell in the moment, and think our thoughts, and don’t feel obliged to draw conclusions,” says Motion. “In fact, to meditate, really, on the inconclusiveness of life.” He pauses, briefly, before arriving at a sentiment of which Larkin would surely have approved. “Except that it’s going to end.”