There have been many exhibitions of ancient Egyptian art held in Australia. Pharaoh, at the National Gallery of Victoria, is outstanding for its scope, scale and presentation.

It is the greatest exhibition of ancient Egyptian art we have ever seen in Australia.

The exhibition comes from the British Museum, holder of the largest and most comprehensive collection of Egyptian antiquities outside the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Over 500 items have been selected, including monumental sculptures, tomb and temple architecture, coffins, papyri, funerary objects and an extensive display of jewellery.

Numerically, this is the largest (and heaviest) touring exhibition ever mounted by the British Museum and it is the largest exhibition of ancient Egyptian art ever shown in Australia. The effective dramatic display, designed by Peter King who treats the whole space as a cycle from dawn to dusk, occupies all of the major downstairs exhibition spaces at NGV International.

The functionality of art

For a civilisation that left such a huge artistic heritage, it is sobering to remember the ancient Egyptian language had no word for “art”.

Art was something functional that gave permanence to the objects of this world, so they could continue to serve their owners in the next life. Much of the surviving ancient Egyptian art is tomb art, designed to withstand the test of time and to preserve in an idealised form the beauty of balance, order and harmony, while celebrating the absolute power of the pharaoh.

What is it about ancient Egyptian art that holds us spellbound? In part, it is the sense of sublime beauty, its permanence, with forms seemingly unchanging over millennia, its antiquity and its state of preservation. More than anything else it is the fact that it is permeated by a sense of magic, somehow meant to overcome the forces of death.

When a person died, they were mummified and engaged in a ritual involving an interaction with the “ka” (life force) and the “ba” (human essence). They were surrounded by what we could think of as art objects that involved magic spells, magic amulets and protective deities.

What struck me about this exhibition was this sense of spirituality – the mystical otherness. We are presented with a variety of beautiful objects across seven thematic categories. Each section, in a way, comments on the role of the pharaoh in Egyptian life.

The elaborate and the intimate

In an exhibition of this nature, there are a number of memorable objects: the granodiorite Head of a colossal statue, probably King Amenemhat III; the life-size sandstone seated Statue of Pharaoh Sety II wearing emblems marking his royal status; the monumental red granite Statue of a lion erected by Pharaoh Amenhotep III, reinscribed by Pharaoh Tutankhamun; the limestone Statue of future Pharaoh Horemheb and his wife; the huge painted limestone Relief showing King Mentuhotep II wearing the red crown; and the imposing monumental limestone sculpture of the Statue of Ramses II as a high-priest.

All of these are huge works with a dominating presence, a marked frontality and a sense of permanence.

What intrigued me were some of the more intimate, immensely elaborate jewellery-like pieces that served as seals, rings, plaques, amulets, pendants, beads and earrings.

These include: the ornament of a winged Scarab holding a sun-disc, depicting the throne name of King Senusret II with its pieces of lapis lazuli; the faience Throwstick of Pharaoh Akhenaten – an ancient Egyptian boomerang; Girdle with amulets, beads and pendants made of electrum, silver, lapis lazuli, feldspar, amethyst, cornelian, glass; and the Ornament with a bull’s head on a gold mount decorated with uraei and lotus flowers made of gold with the bull’s head carved into a piece of lapis lazuli.

While one may be seduced by the ornamental design, the exquisite craftsmanship and precious materials, there is also something ethereal about these objects of beauty.

They were intended to ward off evil spirits and beg for their owner’s smooth transition into eternal life, where the person could experience life in their present form but free of pain, illness or hardship.

3,000 years of art

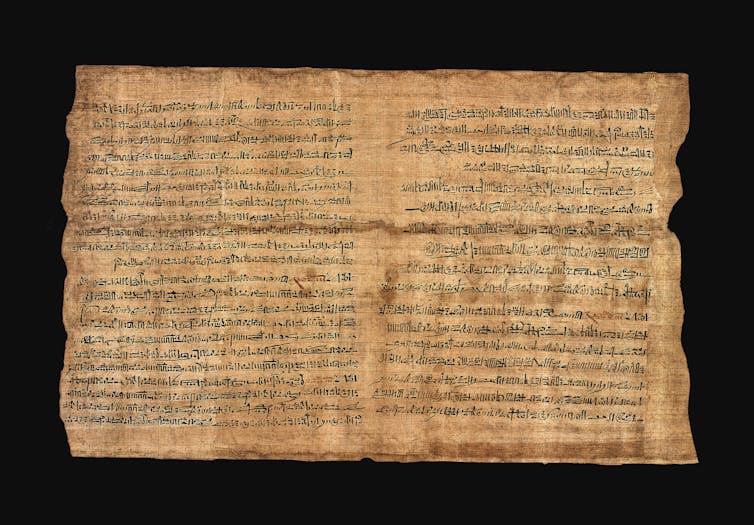

The Book of the Dead (more accurately translated as the “Book of Coming Forth by Day”) was a collection of magic spells intended to assist a deceased person’s journey through the underworld. The texts were prepared for a specific person and speak of the needs of a particular individual.

Since I was a child, I loved reading this book as it was the voice of an ancient Egyptian speaking directly to me.

One passage reads:

There is no sin in my body. I have not spoken that which is not true knowingly, nor have I done anything with a false heart. Grant you that I may be like to those favoured ones who are in your following, and that I may be an Osiris greatly favoured of the beautiful god.

This beautiful and significant exhibition traces the art of ancient Egypt for 3,000 years from the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt and the beginnings of the Old Kingdom with the development of hieroglyphs, in about 3000 BCE, through to the Roman conquest.

A solemn divine majesty runs throughout this exhibition as it celebrates the eternal and magical power of art.

Pharaoh is at the National Gallery of Victoria until October 6.

Sasha Grishin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.