With its shiny new housing estates, scores of building sites and bustling city centre, Jena represents the fresh face of the former East Germany.

"The former East German states now play a full part... in the success and strength of our economy," Chancellor Olaf Scholz said at a meeting in the city this week.

Economic problems and a general sense of being disadvantaged are often cited as the reasons why support for the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) is particularly high in the once-communist East Germany.

The AfD emerged as the biggest party in eastern Germany in June's European Union elections and also looks set to make big gains at regional polls in Thuringia and Saxony on Sunday.

But in fact the former East German states have racked up a slew of positive economic data in recent years, with investment on the rise and unemployment falling.

"For the past 10 years, growth in (eastern Germany) has been higher than the national average," Axel Lindner, a researcher at the IWH Halle economic institute, told AFP.

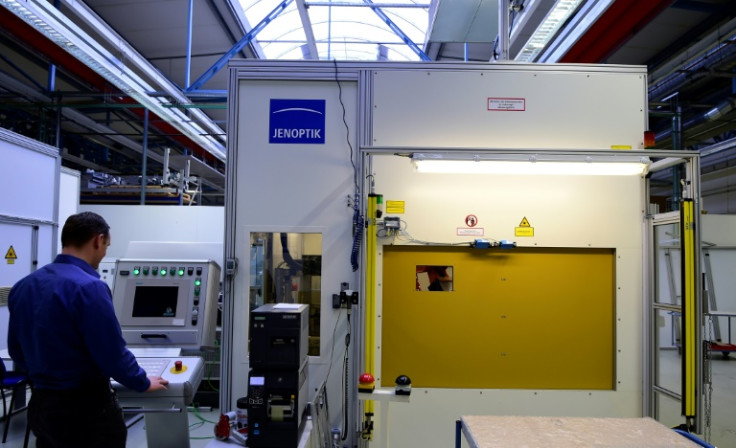

As the economic centre of Thuringia, Jena is a world-renowned centre of expertise in the field of optics, with a thriving start-up scene and renowned universities.

In neighbouring Saxony, the city of Dresden has become a hub for the semiconductor industry.

Eastern Germany's GDP will grow by 1.1 percent this year, almost three times the national average, according to the IFO economic institute, while unemployment fell from 11.6 percent in 2013 to 7.8 percent in 2023.

While the German economy as a whole has stagnated over the past 12 months, partly due to its reliance on exports, the economy in the east of the country, dominated by family businesses and services, has held up well.

Eastern Germany has also been chosen as the location for several large industrial projects, such as Tesla's electric car plant in Brandenburg, the state that surrounds Berlin.

Partly thanks to the factory, Brandenburg was able to rack up growth of 2.1 percent last year while the country as a whole went into recession.

"Something has happened that we didn't expect: we are the top performers," said Carsten Schneider, the government's commissioner for East German affairs.

Consumer purchasing power has also risen faster in the east than in the west, thanks to recent increases in pension payments and the minimum wage.

Incomes and wealth are still lower in the east, but the gap is narrowing -- wages in eastern Germany were around 91 percent of those in the west in 2022, compared with 80 percent in 2015.

However, the picture is different in the region's rural areas, where the mass exodus of workers and an ageing population and have led to a stubborn sense of pessimism.

According to a study by the IW economic research institute in Cologne, the shrinking population in rural areas could be the root cause of the region's high number of protest voters.

"There is a correlation between population decline and pessimism among residents" fuelled by a sense of deprivation and the "disappearance of public services", Matthias Diermeier, an author of the study, told AFP.

Ironically, the reduction in immigration called for by the AfD could exacerbate this problem and harm the economy, worsening a growing shortage of skilled workers.

By 2030, the working-age population in the eastern regions of Germany is set to fall by 800,000, according to government estimates.

In the run-up to the elections in Saxony and Thuringia, many business leaders have warned the far right could threaten economic development, stressing the importance of diversity and openness.

It was in Jena that the Prussian army was defeated by Napoleon in 1806, sparking the beginnings of German nationalism.

But the AfD scored only 15 percent of the vote in the city in June's European elections, well below the rest of eastern Germany.

"When you have money in your pocket, you're automatically less likely to vote for the extremes," Thomas Nitzsche, the mayor of Jena, told AFP.