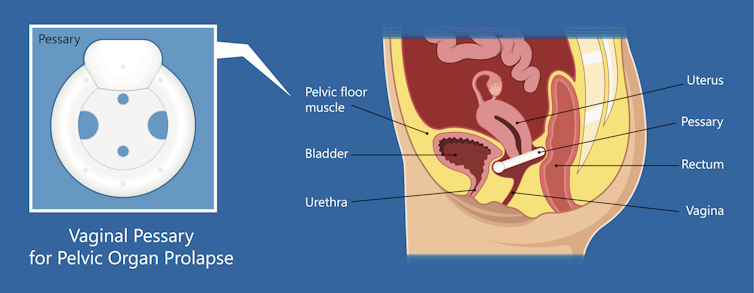

A vaginal pessary is a removable device inserted in the vagina to support its walls or uterus (support pessary) or for bladder leakage (continence pessary).

Pessaries have been around for a very long time, the oldest known pessary – as described by the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates – was a pomegranate soaked in vinegar!

Nowadays, pessaries are made from silicone which is non allergenic, long lasting, pliable and can be sterilised. Some are worn continuously for weeks, months or years with appropriate maintenance, while others are inserted as needed.

What they are good for

There are many types of vaginal support pessaries with (mostly) descriptive names: ring, Gellhorn, donut, cube, C-POP and more. At least two models of continence pessaries – branded Contiform and Coo-Wee – are relatively new on the market as well as the continence ring and dish.

Continence pessaries are used for stress urinary incontinence or “light bladder leakage” that occurs with coughing, sneezing or exercise. These act to support the urethra, as can a vaginal tampon, and can prevent leakage in up to 60% of women. They are especially useful if leakage is predictable, such as when a woman goes to the gym or out for a jog.

Vaginal support pessaries can be effective for prolapse (a type of hernia or weakness of the vaginal walls and ligaments that allow the uterus, bladder, or bowel to descend to or beyond the vaginal opening). If successfully fitted, pessaries can help 60% to 70% of women with these problems. There is improvement in the feeling of a vaginal bulge or tissue protrusion, improvement in bladder emptying and bladder leakage and urgency, sexual frequency and satisfaction. About 50% of women who have a vaginal birth will have some prolapse and up to 20% will go on to have surgery during their lifetime.

Pelvic floor muscle training in the early stages can improve symptoms as can vaginal estrogen in women after menopause. A pessary can be an alternative to surgery or used while women are delaying (such as in between pregnancies) or waiting to have surgery.

Read more: Why you shouldn't make a habit of doing a 'just in case' wee — and don't tell your kids to either

The downside

Pessary use can have a downside too. Side effects may include vaginal discharge or odour or vaginal bleeding. These side effects generally occur after many months or years of continuous use and contribute to discontinuation.

An Australian study reported only 14% women continued long term use of pessaries mainly due to these side effects and the need for long term maintenance.

But a pessary can “buy time”. Theoretically, pessary use can help prevent worsening of prolapse.

A pessary for longer wear is usually fitted in clinic. Generally, all gynaecologists are trained to fit a pessary as are specialised pelvic floor physiotherapists and continence nurse specialists. Women often require a trial of more than one size or type to find the “best fit”. Sometimes a pessary can’t be fitted, is uncomfortable or falls out. This can occur when the vaginal length is short after previous prolapse surgery or hysterectomy, the vagina has a wide opening or the muscles are very weak.

Support pessaries can be self-managed by women who are willing to do this regularly in the same way they might manage a tampon, menstrual cup, or diaphragm contraceptive device. Sexually active women may choose to remove the pessary prior to intercourse; however, this is not essential for all types.

If not self-managed, pessary follow up is needed every six to 12 months, when the device is removed, cleaned, and reinserted or a new one inserted.

There are rare but serious complications like fistula (an opening between vagina and bowel or bladder) and impaction where an anaesthetic or surgery is required to remove the pessary.

Read more: Playing games with your pelvic floor could be a useful exercise for urinary incontinence

Some future models

Recently, there is some research and development occurring in adding personalised or “smart” capabilities to the vaginal support pessary such as electrical stimulation therapy or pressure biofeedback such as already exists for pelvic floor training devices.

Acceptance of pessaries is variable and often related to prior knowledge and appropriate counselling.

There is a lack of knowledge and awareness regarding how common pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence are. We often hear women express embarrassment, shame or fear but many suffer in silence. The main barrier to seeking treatment is the perception that prolapse or incontinence are inevitable parts of childbirth and ageing.

Prolapse and urinary incontinence can have a negative impact on a woman’s physical, emotional and social wellbeing. Women experiencing any pelvic floor dysfunction can speak to their GPs, gynaecologists, or urogynaecologists (gynaecologists specialised in management of prolapse and incontinence).

Read more: Explainer: what is pelvic organ prolapse?

Anna Rosamilia is Clinical Associate Investigator for studies receiving funding from NHMRC, Past research grants from Boston Scientific, American Medical Systems. Astellas. She has had an expert witness role. None of this funding is related to pessaries. She is affiliated with and member of International Urogynecological Association, Urogynaecological Association of Australia, Continence Foundation of Australia and International Continence Society.

Mugdha Kulkarni is a member of International Urogynecological Association & Urogynaecological Association of Australia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.