Matt Furie, a San Francisco-based cartoonist of reluctant notoriety, is a frog lover. He’s always drawn frogs: goofy frogs, peaceful frogs, frogs on bike rides, frogs having tea. “It’s just been kind of a slow drip of frogs throughout my entire life,” he says at the start of Feels Good Man, a new documentary about him and the character who leapt out into a life of his own. “Eventually, it was Pepe. He’s a happy little frog.”

Most people who have seen images of the now-infamous Pepe the Frog probably wouldn’t describe him that way. In the years after Furie created him for his lighthearted comic Boy’s Club, Pepe the Frog became a wildly popular internet meme. After catching on with weightlifters on Myspace, Pepe became the unofficial face of the anonymous imageboard site 4chan, and then exploded on other social media. Users redrew images of him as sad, smug, rageful, and sometimes violent: There has been school shooter Pepe, 9/11 Pepe, Nazi Pepe. In 2016, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) designated Pepe the Frog a hate symbol.

Directed by Arthur Jones and co-produced by Houstonian Giorgio Angelini, the Sundance award-winning Feels Good Man—which was scheduled to premiere at South by Southwest—takes us through the underbelly of the alt-right, drawing on complex research, data, and theory. But most of all it grounds us in Furie’s strange, unprecedented experience of accidentally creating a meme and watching his character morph into something unrecognizable.

Feels Good Man, which launched on streaming platforms and in some indie movie theaters in September, follows Furie’s quest to get Pepe removed from the ADL’s list of designated hate symbols. He gives speeches and launches a social media campaign called #SavePepe. He sues alt-right figures, like Austin’s Alex Jones, who sell Pepe merchandise. But the internet is too vast and chaotic for the admittedly endearing efforts of his tight-knit community to turn the tide. When a higher-up from the ADL says they simply can’t take Pepe off the hate symbol list, we know he’s right. Still, the film captures something less concrete and more wondrous: an exploration into the soul of American culture and the landscapes of cyberspace, and a cautionary tale rich with beauty and meaning missing from the nihilism with which Pepe has been poisoned.

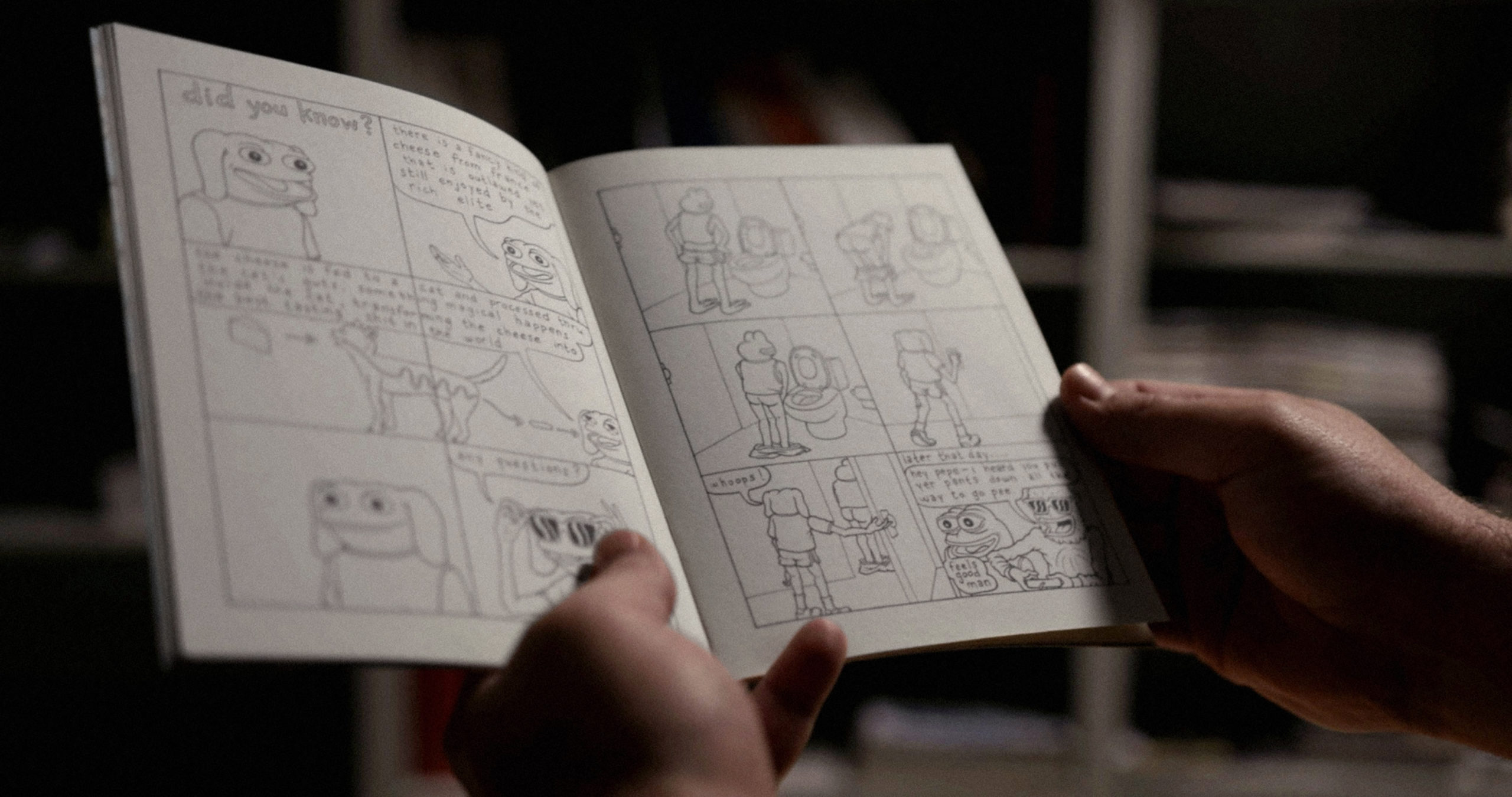

Early on in the film, Furie’s friends and peers describe Boy’s Club as fun, unserious, and “one of the funniest comics of the last 10 years.” Originally inspired by Furie’s own friend group and their hijinks after college, the comic casts Pepe as “the little brother” character. He and his animal friends drink beer, smoke from bongs, play video games, and get dumb tattoos. In the frame that “started it all,” according to Furie’s partner, Aiyana Udesen, Pepe goes to the bathroom and pulls his pants all the way down to his ankles to pee. When his friend later asks why, Pepe simply responds: “Feels good man.”

The line works as a mantra for the film as it tracks how Pepe was turned upside down. Instead of a good feeling, memes of him mutated to express something that “feels bad man.” Predominantly young men on 4chan—a forum website known for its total anonymity, influential memes, and politically charged controversies—used the so-called “Sad Frog” to show anguish, dissatisfaction, and anger. Researcher Aleks Krotoski says that Pepe’s popularity exploded at the same time other parts of the internet, like Instagram, were starting to commodify positivity, monetizing images of happiness. “I think for a huge population, online and offline,” says Krotoski, “we’re not really allowed to express sorrow or sadness or grief.”

From there, the worst impulses of the 4chan niche festered and turned dangerous. Writer Dale Beran explains that memes on 4chan have historically been presented with a mocking sense of humor, a guarded irony, a pretense that the celebration of white supremacy and mass shootings is so inflammatory that it’s just a joke, harmless on the screen of a webpage. In 2014, after Isla Vista shooter Elliot Rodger went after women as “retribution” for rejecting him, the hero status 4chan users afforded him exposed that this stance was not in fact a joke at all.

Jones and Angelini indicate that Pepe memes reflect this crisis of masculinity. When cheerful young girls started gravitating toward memes of Pepe, 4channer boys viciously attacked them and drove them off the site. The rage and hostility seen in memes of Pepe and in his alt-right followers drastically departs from the sweet frog in Matt Furie’s cartoons, and the type of man he appears to be. In one interview, a female cartoonist friend of Furie’s lovingly pokes fun at the boyish potty humor in his comics: “It’s the sort of masculinity where you can be in your underwear singing to Shania Twain,” she says, referencing a frame of Boy’s Club. The masculinity celebrated in the comic doesn’t resemble the “online male supremacist ecosystem”—as the Southern Poverty Law Center calls it in their list of hate groups—that’s thriving among “incels” and other young, predominantly white men in subreddits, 4chan, and 8kun.

Hatred isn’t the only thing festering in these spaces: So too is the unsettling potential for alt-right men to remake reality, matched only by Trump himself. Drawn to Trump supposedly as a joke, these users came to identify with him in 2016, seeing him as the ultimate troll and a master of the media. Images emerged of Trump as the personification of the smug Pepe meme, a recasting embraced by the then-candidate. As the film tells it, the memification of Trump accelerated users’ support: “Time to warp reality,” they posted, and “Make the meme real.” When Trump won the presidency, 4chan celebrated: “We memed a man into the White House.”

Feels Good Man is a marvel of documentary filmmaking of the Trump era. It captures a quiet terror at the heart of this moment: that any semblance of objective truth will break down, and the nightmare delusions of the internet will replace it. Trump’s team knew the political weight of memes, whether they were created by American or Russian trolls. His former tech strategist Matt Braynard states in the film that the production of far right memes was a campaign tactic. On the other hand, the decontextualization of the internet has already allowed for Pepe to find new meaning. Out of nowhere, youth protestors in Hong Kong are using him as a symbol of resistance against authoritarianism. But here in the U.S., this frog is still sick, dragging misery in his wake.

As the film comes to a close, Jones leaves us with no illusions about where the real, the compassionate, and the meaningful actually are. A stunning, vibrant animation shows three Boy’s Club characters standing at the bottom of an Egyptian pyramid flanked by two stone Pepes. The voice of author and druid John Michael Greer takes over; he imagines Pepe to be an omen. “In a lot of traditional societies, it was very standard to look for omens,” he says. “That was a warning that something was shifting in society, something had gone wrong, or there was something building that you needed to know about before it arrived. Pepe the Frog is an omen. We need to listen, because it’s not going to go away until we hear the message that it has to say.” At the top of the pyramid, storm clouds clear, and a calm Pepe turns back to smile at his friends, before swimming away into a pink-orange sunrise.

Read more from the Observer:

-

A Monumental Undertaking: Protests to remove racist statues and iconography are part of a larger effort to reframe Texas history.

-

Beyoncé Isn’t Possible Without Houston. Houston Isn’t Possible Without the Black Diaspora: Texas’ artistic innovation is nothing new and continues to be center stage through artists like Beyoncé during yet another period of Black rediscovery.

-

Why Does John Cornyn Tweet?: An analysis.