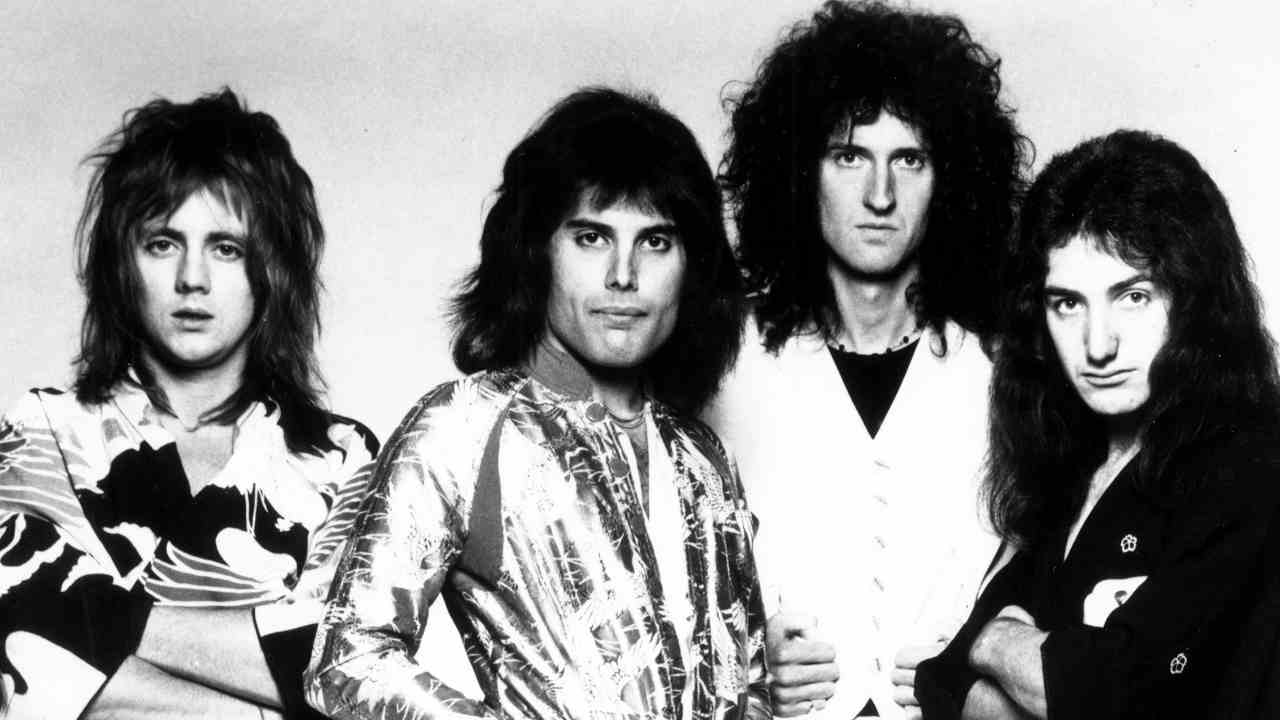

In 1975, Queen were an ambitious band hungry for superstardom – and then they released their fourth album, A Night At The Opera, and monster hit single Bohemian Rhapsody. Former Melody Maker journalist Harry Doherty was on hand to watch it explode.

It could have been any other damp, cold Friday afternoon in the November of any other year. But this one was a bit special… 1975 was heading for Christmas and I was in the middle of a music mag office in sole, exclusive possession of the album, the song, from the band that would rule the world of rock for the next 30 years. Full of anticipation, I put the test pressing on the office turntable and something called Bohemian Rhapsody soared out. Well, it soared for me: it dive-bombed for others in the office. One colleague, Allan Jones, was horrified: “What is this?!” He guessed at 10cc. When I told him that it was Queen, his jaw dropped and hit the floor. He hated it! I loved it, and went on to review Queen’s A Night At The Opera for Melody Maker.

I said things like ‘easily their best work to date’, some words about ‘intricate musicianship’ and ‘displaying the variety of their talent’, commented that it would be remembered as an album of ‘May classics’ (was it?), and hooked unashamedly on to Bohemian Rhapsody. ‘The album,’ I wrote, ‘picks up the best of the concepts of Queen II and combines it with the studio expertise of Sheer Heart Attack. That combination, plus the growing maturity of the band, has given Queen a complete identity. Indeed, I don’t think I’d be too far out if I said that Queen could well set a future direction in British rock’n’roll. They’re hard rock, but just commercial enough to capture a massive, wide-ranging audience.’

I think I was on the button with that one…

All these years later, friends have come and gone – goodbye, Fred – but Queen, in one shape or other, are still very much with us. The band as we know now are a part of the fibre of our rock community.

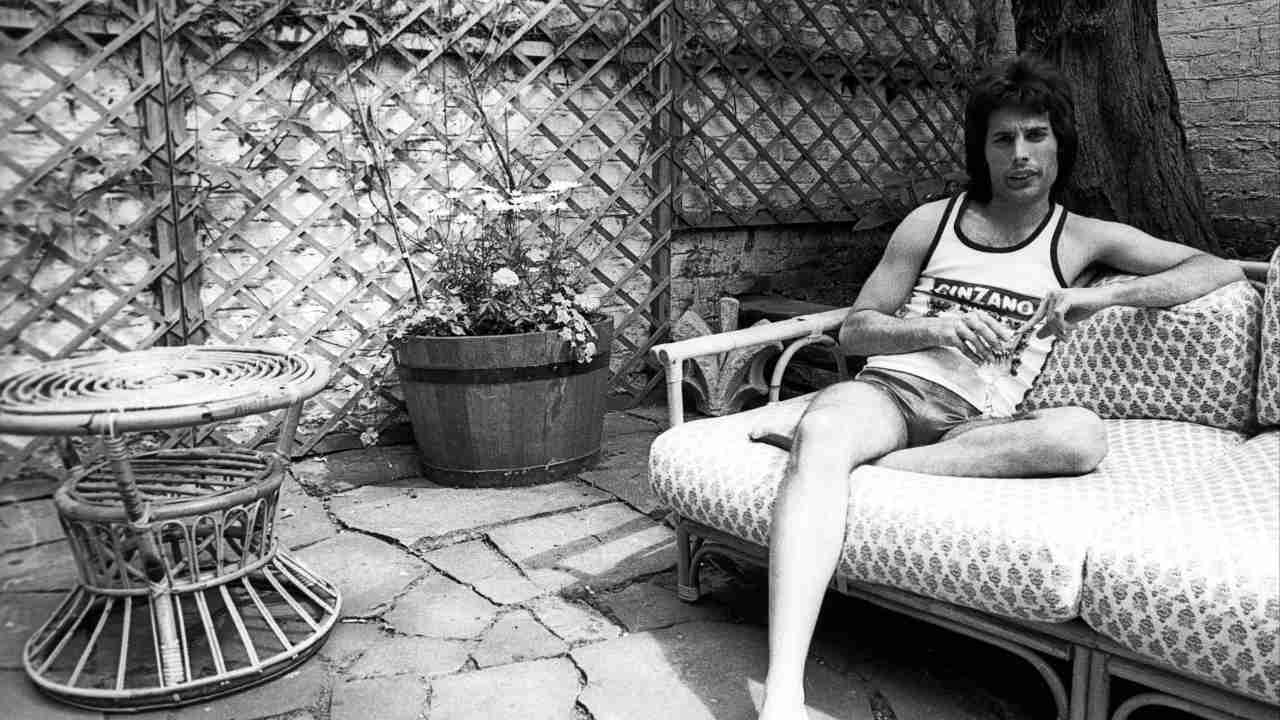

Back in the mid-1970s, however, Queen were mere mortals – not that they thought so. When you were was in the presence of Freddie Mercury, you knew it… and you believed it. With Sheer Heart Attack on the verge of release, I’d interviewed His Majesty in the office of his press officer, Tony Brainsby. Nothing could have prepared me for the experience… but I soon learned. Sheer Heart Attack is as close to hard rock-cum-pop perfection as you can get; but even then, the album in the bag, treading on the doorstep of humungous success, Freddie is not happy. And he’s not happy that they had to record this album in bits and pieces; a situation generated when Brian May, suffering from hepatitis, took to bed and recovery while the other three recorded the tracks.

May had returned with the condition after the band’s debut tour in America with Mott The Hoople. So when they started recording Sheer Heart Attack, it was without their guitarist. He came in afterwards on his own to add guitar. Though the ailing Brian had delivered his parts to a superlative album like a true guitar hero, Freddie was adamant that Brian had brought this upon himself. “Well, darling,” he said, “we covered for him. He owed it to us.”

A year later, November 1975, I’m in the presence of greatness again as Queen are close to finishing what would be recognised as the album of their lives, A Night At The Opera. We’re in the offices of Rocket Records, because the band have by this time appointed John Reid, Elton John’s chargé d’affaires, as their business manager; Reid had been appointed after an earlier disastrous management contract with a company called Trident, who also owned the studios where Queen recorded most of their early albums, including A Night At The Opera. It obviously went seriously sour, as described in the opening track of A Night At The Opera, Death On Two Legs, with barbed lyrics such as: ‘Screw my brain ’til it hurts/You’ve taken all my money – and you want more’ and ‘You’re a sewer-rat decaying in a cesspool of pride’ – possibly the ultimate put-down. Reid would be a stop-gap until Queen established their own business empire.

For now, though, there’s me, Freddie, John Deacon and Roger Taylor, but no Brian May. The man is exhausted after his efforts recording his parts on A Night At The Opera – they do say that hepatitis lingers on. Taylor is nestled in one corner. A real rock’n’roll animal during these years, he’s restless. “I’m pissed off listening to the bloody album,” he mutters. Four months in the making, the nights with this …Opera have taken their toll.

In another corner of the office, Freddie is on the phone to some American hack telling him, darling: “The album is absolutely wonderful, you really must hear it.” But he, like Taylor, has had his fill of A Night At The Opera just now. Which is ironic because we’re on our way to the first public playback of said masterpiece…

“I’ll never forget this album, dear,” Freddie tells me. “Never. But we’ve got to have this playback just to let friends hear what we’ve been up to. The problem, as I see it, is that they’ll never understand it with one listen.” He can’t wait to get it over with. “Later on we’ll go out, get pissed and put the damned album on hold for a while.”

I’m with you Freddie, I think, but I still can’t wait to hear what you’re so pissed off about…

They’re fidgety. John Deacon is all fingers drumming on desk and picking out faults on the tour programme. The band are going out on a worldwide tour in a week or so. No pressure…

Meanwhile, Freddie is still spreading the good word to the States about the album, and Taylor and Deacon are debating how Bohemian Rhapsody, six minutes long and not exactly yer typical single, will go down. They’re amused, but couldn’t care less. As we arrive at the North London Roundhouse studio for the playback we’re greeted by a placard proclaiming: ‘Welcome to A Night At The Opera’.

“We’re not nervous,” Taylor offers, “we’re just nervous wrecks. I just want to get out on the road again.” The realisation that he has just four days to achieve that particular ambition weighs heavily upon him.

The playback goes extraordinarily well. Everyone realises that they are experiencing something monumental. The record company is pleased, the party is ecstatic, the champagne is flowing – time for Freddie and I to depart. But not before we listen to the final historic rendition of The National Anthem on harmony guitars by Brian May, the glorious closure of A Night At The Opera. We listen in thrall. Freddie can’t believe it. “STAND UP YOU BASTARDS!” he shouts, and whether it is in salute to Queen or The Queen I am still not sure. But we all did his biding as if by royal command.

Then the Mercury Man and myself are in a car and heading to the White Elephant on the River for a tête-à-tête and review of the past couple of months of his life over dinner. “Thank goodness that’s over,” Freddie sighs. “Some of those people really BOO-OORE me.”

On his own, Freddie’s kaleidoscopic personality vibrates. If you are in his company, the feeling you get is that you are the sole purpose for his being; he is so completely entertaining and engrossing. At a top-notch restaurant, he demands the service of someone royal before finally we get down to discussing A Night At The Opera.

“It’s really taken the longest to do out of our four albums so far,” he says. “We didn’t really cater for it. We just set upon it and we were going to do so many things. It’s taken us about four months and now we’ve gone over the deadline with the tour approaching. It’s more important to get the album the way we want it, especially after we’ve spent so long on it.

“The last bits – piecing it together – are more important than the rest of it. It’s easily our most important album yet, to be honest. In a way the best judge we had was tonight because we listened to it back for the first time. We just haven’t had the time to do that. I know that we’ve got the strongest set of songs ever. It is going to be our best album, it really is.

“If I thought there was something wrong with it, I would say so, but there are certain things on this album which we’ve wanted to do for a long time. I’m really pleased about the operatic thing” – ahem, we’re talking about Bohemian Rhapsody now – “I really wanted to be outrageous with the vocals because we’re always getting compared to other people, which is very stupid. If you really listen to the operatic bit, there are no comparisons, which is what we want. But we don’t set out to be outrageous – it’s in us. There are so many things that we want to do but we can’t do everything at the same time. It’s impossible. At the moment, I’m happy that we’ve made an album which, let’s face it, is too much to take for some people. But it was what we wanted to do.”

Mercury considers the impact Queen made with Sheer Heart Attack. It posited them where they wanted to be – in a sphere of influence. Queen II had set the cards on the table; Sheer Heart Attack had stated “here’s what we can do”; A Night At The Opera took it to the limit.

Freddie uses his fork as an exclamation mark, stabbing his food as he speaks. “With Sheer Heart Attack, we thought, we can do certain things and establish ourselves!” Stab! “Like vocally, we can outdo any band!” Stab! “With this album, we just thought that we would go out, not restrict ourselves with any barriers, and just do what we want to do!” Stab!

He considered Bohemian Rhapsody specifically. “I had this operatic ‘thing’, and I thought why don’t we doo-oo-oo it.” His affectation on the ‘do’ really emphasises his determination to achieve something radically different. By then, I’d heard the track a few times. ‘Overboard’ was a word I used to him to describe the work.

“We went a bit overboard on every album, actually,” he responded gleefully. “But that’s just the way Queen is. In certain areas, we feel that we want to go overboard. It’s what keeps us going really, darling. If we were to come up with an album where people said: ‘It’s just like Sheer Heart Attack but there were a few bits on Sheer Heart Attack that are better…’ Well, I’d give up. Wouldn’t you?”

I pathetically nod ‘yes’, as if I had just made an album the measure of Sheer Heart Attack that very evening…

As we tucked into a main course avec bubbly, Freddie, though, was sure that Queen were firmly set on a right royal journey. “What really helped was the last tour. We’ve done a really successful worldwide tour which we’ve never done before. All that experience was accumulating and when we came to do this album, there were certain things which we had done in the past which we can do much better now.

“Our playing ability was better. Backing tracks on this album are far superior. We start off with backing tracks and we really felt they were really closely knit, and we seemed to feel each other’s needs, which is very important for backing tracks.

“I think Queen has really got its own identity now. I don’t care what journalists say – we got our identity after Queen II. With that album, we had our own thing. America saw that it was good, and so did Japan. Since then, we’re the biggest group in Japan. I don’t mind saying that. We are! We outdo anybody. And that’s because we’ve taken it on our own musical terms.

“So since Queen II we’ve had our own identity and, of course, if we do something that’s harmonised, we’ll be The Beach Boys and if we do something that’s heavy, we’ll be Led Zeppelin, or whatever. But the thing is that we have an identity of our own because we combine all those things which mean Queen. That’s what people don’t seem to realise.

“A lot of people have slammed Bohemian Rhapsody but if you listen to that single, who can you compare it to? Tell me one group that’s done an operatic single? I can’t think of one! But we didn’t do an operatic single because we thought we’d be the only group to do it. It just happened!

“The title of the album came at the very end of recording. We thought: ‘Oh God, what are we going to call this album?’” Typically, the two most humorous members of the band reverted to The Marx Brothers, but this was certainly an album made by a group firmly placing collective heads in the noose.

“We’ve always done that,” Freddie agreed. “We’ve always put our necks on the line. We did it with Queen II. On that album we did so many outrageous things that people started to say ‘self-indulgent’, ‘crap’, ‘too many vocals’… but that is Queen. After that, they seemed to realise what Queen was all about.”

And just to tighten the noose, let’s stick out a six-minute mini-opera that possibly stands no chance of getting radio play… “We look upon our product as songs,” Freddie considers gently. “We don’t worry about singles or albums. All we do is pick the cream of the crop. Then we look upon it as a whole to make sure the whole album works.

“With Bohemian Rhapsody, we just thought it was a very strong song and so we released it. But there were so many arguments about it. Somebody suggested cutting it down because the media reckons we have to have a three minute single, but we want to put across Queen as songs. There is no point in cutting it. If you want to cut down Bohemian Rhapsody, it just won’t work.

“We just wanted to release it to say that this is what Queen are about at this stage. This is the single and you’re going to have an album after that.”

And this, asserts Fred, is the uniqueness of Queen. Their USP (Unique Selling Point) is simply: take it or leave it. Like it or loathe it. “We’re just very different. We do things now in a style that is very different to anybody else. But we haven’t acquired that just to be different, it just happened. We go through so many traumas, and we’re so meticulous. There are literally scores of songs that have been rejected for this album – some of them nice ones. If people don’t like the songs we’re doing at the moment, we couldn’t give a fuck. We’re probably the fussiest band in the world, to be honest. We take so much care with what we do because we feel so much about what we put across.

“And if we do an amazing album we make sure that album is packaged right, because we’ve put so much loving into it. It’s what we do, darling.”

The interview finished, Freddie invites his multicolour, multisexual, effervescent, personal entourage to join us – here’s Kenny Everett pushing to the front to embrace and congratulate his buddy on a job well done. Everett was the first Freddie turned to when he realised that Bohemian Rhapsody might not make it to the nation’s airwaves. Six minutes, he told Freddie, you have no chance. And then proceeded to play it something like 10 times on his radio show that weekend. Bo-Rhap was on its way…

The next day, after exposing their masterwork to the fickle elements of the media, the band got together again to listen through to A Night At The Opera one more time before sending it to the pressing factory. And that’s when they decided to remix it…

A few weeks later, and I’m sitting backstage at Hammersmith Odeon talking with Brian May, just as Queen are preparing for a soundcheck for a series of gigs in west London. Sitting there, considering the immensity of what is happening around his band, May is calmness itself.

“We’re a bigger band now and we can afford to plough more into the presentation. We’ve always lived beyond our means anyway! Dynamics are things we consider worthwhile in a show, just so that we can make it a complete evening out for the fans. The glamour will never take away from the music. We’re much too conscious of the music to let that happen.

“The music is first in everything and if we add a particular effect or particular lights, it’s to get across a certain mood at a certain time to emphasise the music.

“You see, you have to understand it’s romantic music we’re playing – in the old sense of the word. It’s music to tear your emotions apart. There’s a kind of personality we share with our audience. We’re like that. We’re sort of schizophrenic. We like to be serious about some things and not as serious about others.”

Ah, and here we have Queen on tour. Here we have in Bohemian Rhapsody and A Night At The Opera, a quintessential ‘studio record’; we have the Queen that proudly proclaim on album sleeves ‘no synthesisers’; the Queen lording it on the road; the Queen that has to reproduce this on stage. How do you square that circle, Brian?

May considered this. “We play differently on stage from on record. On stage, it’s good to have a two-way conversation with the audience rather than oneway. Let me explain this. It’s no good just getting out there and playing if you’re not getting across to the people. We treat recording as a separate thing altogether from the stage act. We don’t have any thought of holding back something on record if we couldn’t do it on stage. There are very complicated things on the record but, hopefully, not complicated for complication’s sake.

“There’s a lot of texture on our albums. We started that with our second album.” You see now that Queen II is a significant album in the growth of Queen. It is my favourite Queen album, by the way. Brian developed the theme. “That album has a lot of impact. If you listen to our albums more and more, you will get more and more out of them.”

Still, as Bohemian Rhapsody and A Night At The Opera were being unleashed, May was ticking the box that said ‘room for improvement’. “I’d like to see us, as a four-piece, work together more on songs. In the case of A Night At The Opera, it was impossible because we didn’t have enough time, and we were in the situation where a couple of us were in one studio and the others in another, so you lose a bit of the group feeling in that way.

“It’s good to be out on the road,” he says. “It draws you together.”

You get a sense that Brian thinks too much, and when he talks to you about A Night At The Opera, he’s what you might call ‘picky’…

“It’s not that there is too much individualism,” he says. “I can point toward things on this album which have suffered from us not having us all there at one time. and because there was too much responsibility on one person at one time very often. I can’t say which tracks because it would spoil it for people. That’s not to say I don’t think it’s a good album. I love it.”

We went on to talk about the Queen modus operandi; how the band got from college to collective. I point out that with four very strong personalities in the Queen ranks, it wouldn’t be surprising that things might get a little bit hectic now and then.

“Generally,” May answers, “the working relationship within the band is that we tend to leave each other alone musically, unless asked. That would be my interpretation. If someone has an idea, you assume that they want to be left alone to get on with it and put it across the best way.

“Sometimes, they’ll come and talk about it, which I do a lot. Maybe I can’t make a decision and I’ll come to the others and say, ‘How does this strike you?’ and they’ll suggest something and usually I’ll agree.

“The relationship gets strained sometimes. I got very worried once that I was going out on a limb and that the rest of the band didn’t really approve of what I was doing. It happened on a track on A Night At The Opera – Good Company. I spent days and days doing those trumpet and trombone things [all of which were played by May on the guitar] and trying to get into the character of those instruments. The others were doing other things and they’d pop in from time to time and say, ‘Well, you haven’t done much since we last saw you…’

“They probably wouldn’t mean it in a dire way, but I would get very offended and very worried that I was doing something which their heart wasn’t in but, in the end, it turned out well.”

And Freddie. What was it about the Mercury-May chemistry, especially when May worked on Mercury songs? How did that work?

“Freddie and I worked together very well. Is it hard? No, quite the opposite. I find it natural. I think he’s got a knack of using me to my best advantage. Usually he has everything sorted out until the last note, calls me over and tells me which way he wants it. There is never any friction.

“He’s got a strong personality. I think we all have. We’re all very stubborn, particularly in the studio, and sometimes it leads to bad feeling. Generally, however, if it comes down to a genuine musical argument, we tend to see eye to eye in the end. We all know where we’re going; it’s just a question of how we get there that is argued about.”

We rattle on about Freddie for a while, laugh about him, his ways and his genius. May could talk on the subject for hours, he says. “Freddie is a born figurehead,” he comments with deep affection. “He loves himself to be used as a figurehead. He knows exactly what’s best for himself.

“Freddie knows exactly what he wants and how to get it. He’s definitely the driving force behind the band getting where it is. He’s flashy but he knows he’s got the substance to back it up. He’ll never be flash in an area where he’s not confident. If there’s something he knows he doesn’t know much about, he’ll steer completely away from it, or he’ll conquer it. There’s no halfway house. He won’t give the impression that he knows what he’s talking about when he doesn’t. He’ll always make sure that he knows what he is talking about and then let everybody know. Some people think that he’s arrogant but in fact, he’s only arrogant when he knows he can afford to be.”

After all, who could challenge Freddie Mercury? The other members of Queen, if anything, pushed their singer to the front and encouraged him to impose his magnetic personality on to the media and public. Such was their confidence in their own musical ability and business nous that they were perfectly happy to let Freddie loose.

“It’s good that Freddie has such a strong personality because he doesn’t let it go to his head, which he could quite easily have done,” says May. “It’s very weird that that happened. We could see it happening from the beginning. He’s our frontman and we consciously used it in that way. The press did, and still do, take it too far. A lot of the press are very dimly aware that the rest of the group exist.

“It would be a big mistake for anybody to disregard the role each member plays in Queen. It really does interlock well as a group and we couldn’t do without any one of us at all. I think if anyone left it would disappear.”

…Only to reappear occasionally, as if by a kind of magic.

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 88, December 2005