“I never have, and I never will, because only one man can sing this song on stage, and that’s my older brother Ronnie Van Zant. So you guys sing for us tonight, OK? Can you let him hear you in rock’n’roll Heaven?”

Placing Ronnie’s Hi-Roller hat on a spotlit mic-stand, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Johnny Van Zant leaves the stage. The band that remains strike up the instantly recognisable opening chords, and Free Bird rings out. It’s 1987, and with those chords, and an audience singing Ronnie’s words in full voice, Skynyrd returned…

As resurrections go, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s is one of the more surprising. And successful. A full decade after the crash that decimated them and seemingly confined them to the annals of rock’n’roll history, the South rose, phoenix-like, from the flames…

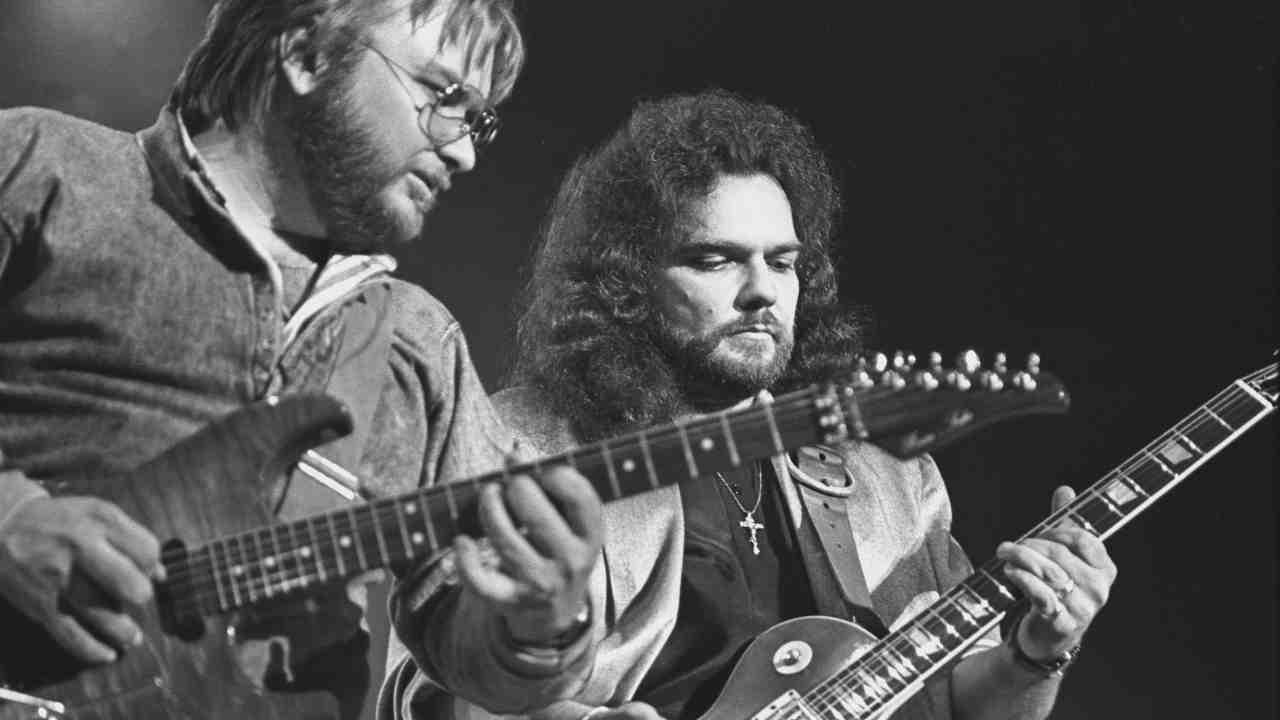

The Starwood Amphitheater, Nashville, Tennessee was jam-packed for Charlie Daniels’ Volunteer Jam, an annual event hosted by the country star to raise funds for muscular dystrophy. Guitarists Gary Rossington and Ed King, pianist Billy Powell, bassist Leon Wilkeson, drummer Artimus Pyle and Ronnie Van Zant’s kid brother Johnny regrouped with the idea of paying tribute to Ronnie and the band he had led.

Time has obscured whose idea it actually was, but it was Gary Rossington who galvanised everyone into action. “That was hard, you know?” he admits, a quarter of a century on. “We didn’t wanna go back out ’cos we didn’t have Ronnie, but I thought Johnny was around singing, and I thought he could sing and sounded like Ronnie. We thought if we could go out and do the tribute to Ronnie with Johnny, we could sound like ourselves. And that’s the way that it went.”

The person who would need most convincing, however, was Johnny. Although he’d released a few albums in his own right at the start of the decade, by the mid-80s he’d reached a pivotal point of his own. Turning his back on the record industry, Johnny was making a sound living being his own boss, freighting goods across the US. Music was in his blood though, and he couldn’t quite let it go. He was still writing songs and recording demos, and the stars would align so that he was on the verge of signing a major recording contract to the tune of a quarter of a million dollars with Ahmet Ertegun and Atlantic Records. Then the phone rang. It was Gary Rossington.

The Atlantic deal was offered on a Monday, remembers Johnny, and it was all in the hands of his lawyers. “On the Friday, Gary called me about being in Lynyrd Skynyrd,” he says. “Within one week, it went boom-boom-boom. That was kind of overwhelming. I was like, ‘Holy crap, I’m just a truck driver!’”

A truck driver, maybe, but one with music in his soul and very deep familial ties to Lynyrd Skynyrd. It was a huge ask: Ronnie was, after all, irreplaceable. Not only in the public’s eyes, but in Johnny’s too.

“I said, ‘I gotta talk to my dad. Then I gotta talk to my brother, my sisters and my mom. I gotta see what everybody thinks.’ Because after the plane crash happened, we were like, ‘This is the end of Lynyrd Skynyrd.’”

Following an emotional meeting of the surviving bandmates and spouses in Bay Meadow in Jacksonville, everyone realised that they didn’t want the plane crash to be the last word in the Skynyrd story. They believed there was a big demand from the fans who wanted to see them play again. The consensus in the room was that they believed Ronnie would’ve wanted them to do it, so the Van Zant family gave their blessing to their youngest son for the one-off tribute tour. But how, and even whether, it would work, was still unclear.

That Skynyrd were getting back together was a surprise for everyone involved, and even more surprisingly, the old magic was still there. “It was fun to start playing again,” Rossington told Classic Rock in 2012. “We had [original Skynyrd guitarist] Allen Collins and Leon [Wilkeson] and Billy Powell. We got everybody left that was alive. And we had our old crew. It was fun to see everybody again.”

The previous year, guitarist Allen Collins had been in a car accident that not only claimed his girlfriend’s life, but also left him wheelchair-bound. But even he was along for the ride, acting as musical director while Randall Hall, his colleague from the Allen Collins Band, stood in for him on stage.

“Allen did the tribute tour with us,” Rossington said. “He had his own bus and it broke his heart, and ours, that he couldn’t come up to play. It was very hard emotionally for him to do that, but we wanted to show the people that we weren’t doing it just for money.

“It was very hard to see him like that, and for him to travel around. He was giving us the OK to do it – he wanted the name and the music to be heard and for us to go about our business. He travelled with us until he just couldn’t anymore. But that was really hard on the band.

Immortalised on vinyl as the double live album Southern By The Grace Of God: Lynyrd Skynyrd Tribute Tour, the rejuvenated band began to realise that there might be more life in the old dog than just playing some shows.

“It just felt sad breaking up the family again after that one tour,” says Johnny. “Plus, the fans wanted it. So we made a new record and hit the road, and we’ve been at it ever since.”

Carrying on wouldn’t be without its difficulties, though. “It got hard after we started playing and doing a tour,” admitted Rossington in 2012. “Everybody had grown apart and separate, and was kind of grown up. We were only in our early 20s when the plane crashed, so after 10 more years you kind of grow up a little more and mature. Things change. So it was harder then. There was a lot of hard feelings and stuff.”

It wasn’t easy for Johnny, either, living up to the spectre of his brother – leading his band, taking control, remaining steadfast for the original members who were relying upon him. Being in the media spotlight, and handling the sometimes insensitive comparisons and critical appraisal, took its toll. But he (and the band) never gave up.

“Probably about the first three or four years, I was very… I don’t want to say uncomfortable, but I still didn’t know if we were doing the right thing,” Johnny says. “But people kept coming and saying how much Skynyrd affected their lives.” It truly was the power of the fondly named Skynyrd Nation that kept them going.

An early obstacle would be the loss of Allen Collins. Having done his best to support the band, he’d never truly recovered from the car accident, and succumbed to pneumonia on January 23, 1990.

“It was a bad time all round for the band. We were still drinking a lot and doing drugs,” said Rossington. “The songwriting was kinda stifled.”

Assuming a songwriting role for Skynyrd was also initially problematic for Johnny. “I admired what they did – they wrote fantastic songs,” he concedes. “I’ve always had people go, ‘Well, how can you write another Free Bird or Sweet Home Alabama?’ And I go, ‘You can’t. That was back then. This is now.’ I never tried. Nobody could ever fill Ronnie’s shoes.”

Of course they couldn’t, but following Collins’ death, the band felt ready to think about entering the studio. Randall Hall remained on guitar in Collins’ stead, and this would be the first time that Johnny would sing for the band in the studio. Released in the summer of 1991, Skynyrd’s first album appearance in 14 years kept it simple. Entitled Lynyrd Skynyrd 1991, it was fairly warmly received, and served as enough impetus to keep the band going.

Touring continued apace until the band reached Canada in August. At which point, drummer Artimus Pyle would be the next to leave the Skynyrd fold, citing issues with drugs and alcohol. There would be animosity from the former drummer in later days, but still Skynyrd found the energy to carry on, with Kurt Custer taking over on drums for the first half of the 1990s.

The Last Rebel came in 1993, and while it was greeted with positive reviews in the rock press, it was decidedly more country-like in tone. But the next pivotal change to Skynyrd would come as Free Bird: The Movie was released. Consisting of footage from a live show shot at 1977’s Day On The Green in Oakland, interspersed with interviews, home movies and documentary material, it highlighted Skynyrd at the height of their powers. It also served as the catalyst for the final piece of the Skynyrd jigsaw falling into place for the new millennium. Rickey Medlocke was now best known as Blackfoot’s lead singer and lead guitarist, but he’d also passed through Skynyrd’s ranks in the very early days, occupying the drum stool back in 1970.

It was a chance encounter that would change the course of Medlocke’s life and significantly contribute to Skynyrd’s upward trajectory. “In 1995 I saw the Lynyrd Skynyrd guys at the premiere for the Free Bird movie in Atlanta, Georgia,” he remembers. “We did an all-star jam, and then in 1996 Gary called me up, I sat down and we played some, and he said, ‘Do you wanna do this?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’ And this was 16 years ago.”

There was no hesitation in Medlocke agreeing to rejoining the band he’d left behind over two decades earlier. “I was looking for something different in my life. So this was really cool,” he says. He kept his commitment to Blackfoot through 1997, but called it a day with the band he’d founded shortly thereafter.

“It was incredible!” exclaims Medlocke about being back in the Skynyrd fold. “You know, I’d missed those guys. I’d always enjoyed playing with that band, so it was great to come back and be playing guitar, because I was the drummer the first time around. To come back in as one of the main guitar players was very gratifying and just an honour.”

It was as if Medlocke had never been away. “We had rehearsed for about a week-and-a-half, two weeks, and the very first gig was in West Palm Beach, the Verizon Amphitheater, in May of ’96,” the guitarist says, proudly. “It was dead on, man. Spot on. It worked. And it’s still workin’.”

Bolstered by Medlocke’s songwriting contributions and renewed enthusiasm, Lynyrd Skynyrd rode out the rest of the 90s with two more albums, the self-explanatory Twenty (referencing two decades since the fateful plane crash) and 1999’s Edge Of Forever, but who could ever have predicted that the dawning of the 21st century and its first decade would see the rejuvenated Lynyrd Skynyrd reach the height of their powers?

As with seemingly everything Skynyrd-shaped though, it wouldn’t be easy ride. The first blow would come on July 27, 2001, when Leon Wilkeson – the band’s stalwart bassist since 1972 – was found dead in his Florida hotel room, chronic liver disease and emphysema claiming him at the age of 49.

“I’m disappointed in Leon,” Johnny told Classic Rock shortly afterwards. “He lived through a plane crash, how can he let booze screw it all up for him?”

Sadly he did, but it didn’t stop Skynyrd. If anything, the loss made them stronger as they headed into the new millennium. Vicious Cycle – an album with an eerily prophetic title given the benefit of hindsight – would drop in 2003, and by mid-decade the band were finally given their due credit as they were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame.

Kid Rock – who has never been shy of proclaiming his love for the Florida band – took to the stage at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel on March 13, 2006, to induct them alongside Black Sabbath, Miles Davis, Blondie and the Sex Pistols. The touring version of Skynyrd – joined by Bob Burns, Artimus Pyle, Ed King and Honkettes JoJo Billingsley and Leslie Hawkins – tore through spirited versions of Sweet Home Alabama and Free Bird.

It was really 2009’s God & Guns that once again marked Skynyrd out as a force to be reckoned with. But, as is seemingly always the way with this band that defies the odds, it was yet another album to be beset with tragedy.

“I’ll be perfectly honest with you. Number one, it’s the best record I’ve done since I’ve been back with this band, and number two, I think this is the best material the band has written,” Rickey Medlocke told Classic Rock at the time of its release. “I think this is the best record since the original band. And it wasn’t easy to do. It was heavy stress, heavy thoughts every day. We lost members while we were making this record. We had to talk to our bass player, who was too sick to play, on the phone. And it was just killing us. I’m glad we got it out for those boys. And they’re very missed right now.”

They were. Guitarist Hughie Thomasson (who had replaced long-timer Ed King) had left the fold in 2005, but he was still very much a part of the greater Skynyrd family, contributing to the songwriting for God & Guns. A heart attack would take his life in 2007.

And that was far from the end of it. Ean Evans, the man brought in in 2001 in place of Wilkeson, would lose his hard-fought battle with cancer on May 6, 2009. And finally, brutally culling Lynyrd Skynyrd’s original members to Gary Rossington alone, a heart attack would take the life of keyboard player Billy Powell.

“We went through a lot putting God & Guns together,” Van Zant says. “You know, I was there a few minutes after Billy died. I pulled up to his condo, and the paramedics were walking down the stairs. I said, ‘What’s going on up there?’ They said, ‘Who are you?’ I told ’em I played in a band with Billy, and they told me he just passed away. Talk about surreal. I drove home feeling completely numb. I was not expecting it. With Ean, he had cancer. He put up a great fight, and he was a very religious guy. They both were, so at least I know they’re both in a better place now.

“But it was our determination: we really set out to finish this thing. We started the record last year and we said, ‘We’re not just gonna finish it, we’re going to make it something those boys would be proud of.’ And I guarantee you that they would be.”

In 2012, they released a new album, Last Of A Dyin’ Breed - a title that was a poignant as it was defiant. As of today, it’s the last record to bear the Skynyrd name. Gary Rossington - the sole remaining founder member, and a survivor in every sense of the word – passed away in 2023, leaving Johnny Van Zant and Rickey Medlocke to carry the torch without him.

“I’m the last original member, so I feel like it’s my job to keep the legacy alive,” Gary Rossington said in 2012. “All my old buddies, all the original guys – Ronnie and everybody – we had a dream to make it big and be heard, and that’s all I’m tryin’ to do, to just keep it going.”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents Lynyrd Skynyrd: Last Of A Dyin’ Breed