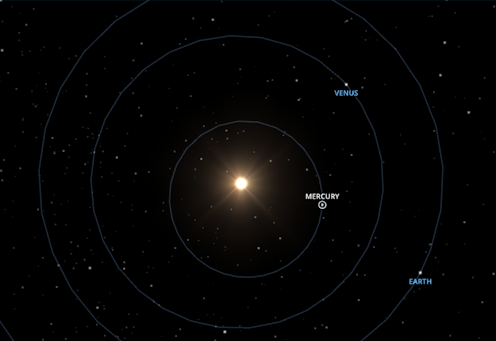

Mercury is the closest planet to the Sun, whipping around our star every 88 days compared to Earth’s 365.25 days. Mercury will also be the first planet destroyed when the Sun expands on its way to becoming a red giant in about 5 billion years.

So it seems a bit rough that we blame Mercury for all our problems three to four times a year when it’s in retrograde. But what does it mean when we say Mercury is “in retrograde”?

A matter of orbits

Retrograde motion means a planet is moving in the opposite direction to normal around the Sun. However, the planets never actually change direction. What we are talking about is apparent retrograde motion, when to us on Earth it looks like a planet is moving across the sky in the opposite direction to its usual movement.

Because Mercury is closest to the Sun and has the fastest orbit, it appears to move backwards in the sky more often than any other planet.

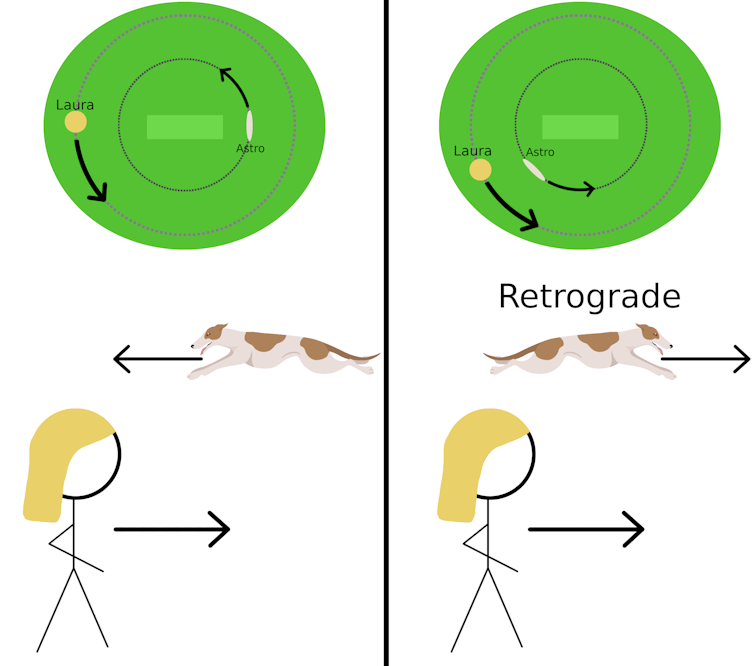

Let’s use my dog Astro to help explain what’s happening when we see a planet in retrograde. Astro is a whippet, or a mini-greyhound, and he has a need for speed. If I take Astro for a run on my local cricket oval, he does super-speed laps on the inside while I run much more slowly around the outside.

If we’re both going anti-clockwise around the cricket pitch, when Astro is on the opposite side of the oval to me it looks like he’s going left while I’m jogging right. But when he gets to the same side of the oval as me, it suddenly looks like he’s running right instead of left (retrograde).

This happens because Astro is going much faster than me, and is inside my “orbit” of the oval.

Because Mercury’s orbit is inside Earth’s orbit, seeing it from our planet is like me watching Astro run.

But Mercury isn’t the only planet to do this. Venus also orbits inside our orbit of the Sun, zipping around once every 224.7 days. This means Venus is in retrograde twice every three years.

The other retrograde

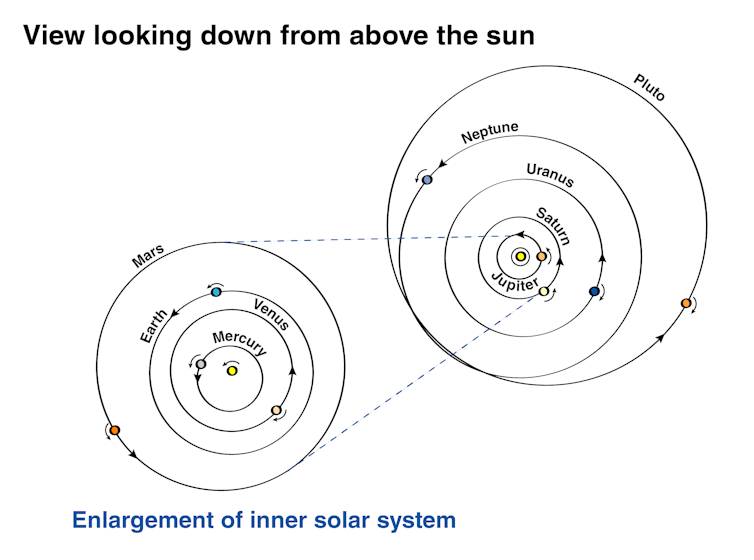

It works the other way around, too. The planets outside our orbit (Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) also go into retrograde.

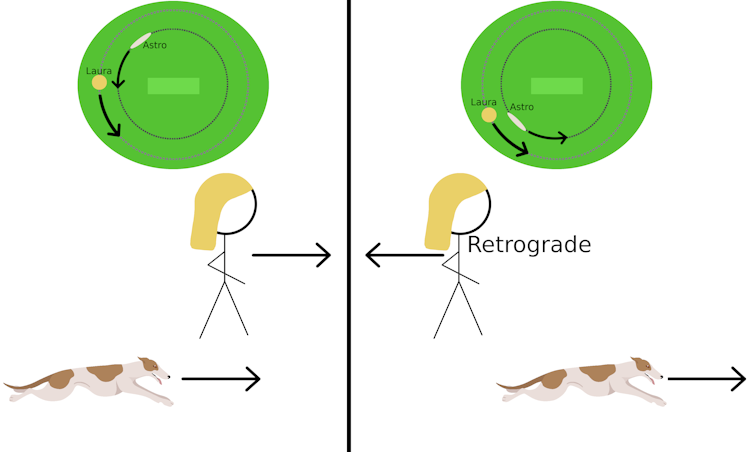

To work this out, we need to swap our perspective. Astro is definitely not a deep thinker, but let’s imagine for a moment that he is and think about what he sees as he runs around the oval.

He’s running around the oval and he starts catching me up from behind. At this moment it seems like we’re both going the same direction, to the right. But as he starts to pass me, it seems like I’m going backwards or left (retrograde) while he continues to run forwards to the right.

This is what happens when we look up at the sky and see one of the outer planets in retrograde.

Mars is in retrograde once every two years. The other planets are so far from the Sun and travelling so slowly compared to Earth that it’s almost like they’re standing still. So we see them in retrograde approximately once a year as we whip around the Sun so much faster than they do.

A well-known illusion

Retrograde motion bamboozled ancient astronomers since humans started looking up in space, and we only officially figured it out when Copernicus proposed in 1543 that the planets are orbiting the Sun (though he wasn’t the first astronomer to propose this heliocentric model).

Before Copernicus, many astronomers thought Earth was the centre of the universe and the planets were spinning around us. Astronomers like Apollonius around 300 BCE saw the planets going backwards, and explained this by adding more circles called epicycles.

So, humans found out retrograde motion was an optical illusion 500 years ago. However, the pseudoscientific practice of astrology continues to ascribe a deeper meaning to this illusion.

There’s a retrograde most of the time

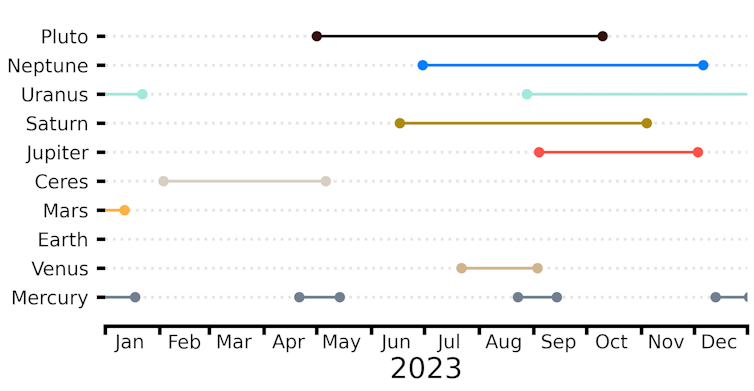

If we consider the seven planets other than Earth, at least one planet is in retrograde for 244 days of 2023 – that’s around two-thirds of the year.

If we include the dwarf planets Pluto and Ceres (and exclude the other seven dwarf planets in the Solar System), at least one planet or dwarf planet is in retrograde for 354 days of 2023, leaving only 11 days without any retrograde motion.

I like to think the biggest impact the planets have on Earth is bringing wonder and joy every time we turn our eyes (and our telescopes) to the night sky. Astro, on the other hand, is happy as long as he gets to run around the oval and bark at possums.

Read more: From platypus to parsecs and milliCrab: why do astronomers use such weird units?

Laura Nicole Driessen is part of MeerTRAP, which is supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 694745).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.