A new lawsuit against a Florida school board marks a “first-of-its-kind challenge to unlawful censorship”.

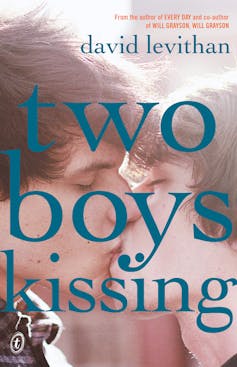

On May 17, the world’s largest English-language publisher, Penguin Random House, free-speech organisation PEN America, five authors (including bestselling queer YA author David Levithan) and two parents joined forces.

Their lawsuit claims Florida’s Escambia County School Board has “unlawfully” removed or restricted books about “race, racism and LGBTQ identities”, and those by non-white and/or LGBTQ authors.

“The School District and the School Board have done so based on their disagreement with the ideas expressed in those books,” reads the lawsuit.

It argues the book removals (and/or restricted access to books), against the recommendations of the district review committee charged with evaluating book challenges, violate the First Amendment, which protects freedom of speech. It also argues school officials violated the Equal Protection clause of the 14th amendment.

Nearly 200 books have been targeted in the district in the past year, according to publicly available information. CNN reports that more than half of those titles have been placed under restricted access and require parental permission during the review process, and 16 books have been either removed from all libraries or made only available for certain grades.

The lawsuit asks for books to be returned to school library shelves, “where they belong”.

PEN America CEO Suzanne Nossel says the book removals are “a deliberate attempt to suppress diverse voices”.

A history of underrepresentation

Children’s books about people of colour have historically been disproportionately underrepresented across Western countries, including the UK and Australia.

A UK survey found that only ten percent of children’s books feature Black, Asian or minority ethnic characters, and just five percent have such a protagonist. This percentage shows a clear underrepresentation of children from minority ethnic backgrounds, who account for 34.5 percent of UK school children.

Similarly, Australian research from 2020 shows “First Nations groups are commonly absent from children’s books.” As stated by researchers at Edith Cowan University:

A world of children’s books dominated by white authors, white images and white male heroes, creates a sense of white superiority. This is harmful to the worldviews and identities of all children.

This speaks to the idea of “windows and mirrors”, a term first coined by Dr Rudine Sims Bishop in 1990, in reference to the lack of people of colour in children’s literature. Bishop argues children need both windows (the ability to see others) and mirrors (the ability to see themselves) in their books. She writes:

When children cannot find themselves reflected in the books they read […] they learn a powerful lesson about how they are devalued in the society of which they are a part.

Read more: Children's books must be diverse, or kids will grow up believing white is superior

Censoring LGBTQ themes

Books by LGBTQ authors or covering LGBTQ themes have a long history of censorship. One of the first picture books to show same-sex parents, Heather Has Two Mommies, has faced many challenges since its original publication in 1989. These include protests, 42 attempts to remove the book from American schools and libraries, and even book burnings.

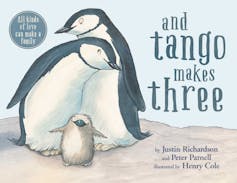

More recently, the picture book And Tango Makes Three, which tells the true story of two male penguins who raise a chick together at Central Park Zoo, has met similar challenges. The book featured on the American Library Association’s Top Ten Most Challenged Book List eight times from 2006 to 2017 for depicting same-sex parents, and is “one of the most challenged books of all time”.

In Australia, the 2015 picture book Mummy and Mumma Get Married was questioned over its “appropriateness” for school libraries. Although seen by some as controversial, the book was largely positively received. However, some Catholic schools refused donations of the book to their school libraries.

Queer Australian YA author Will Kostakis’s latest novel, We Could Be Something, is a “part coming-out story”. He recently shared that when visiting religious schools as an author, he’s sometimes cautioned not to talk about his work if staff haven’t read (and presumably vetted) it first. He believes there’s a link to the current US culture wars.

“We can feel smug about the fact we don’t have politicised school books in Australia, but this move to ‘protect’ kids from queerness is bleeding into Australia,” he told me.

“We see it in the threats and intimidation that has seen drag storytime events be cancelled. We see it in schools, where teacher librarians who build collections that feature books that speak to current teen experiences, some of them queer, fear that one parent who might complain about content.”

A recurring theme in response to Mummy and Mumma, as well as other LGBTQ books, is the idea children needed to be “taught” about same-sex parented families at a specific, appropriate age.

Conversely, heteronormative relationships are not seen as something that needs teaching, or left for discussion until a child is “old enough to understand”. Rather, as the default “norm”, heteronormativity is something children are exposed to from birth without explanation.

This “heterosexism” can prevent children with heterosexual parents from acknowledging – or understanding – that same sex parented families are “real” families.

Read more: 5 books for kids and teens that positively portray trans and gender-diverse lives

Left and right argue against ‘indoctrination’

According to research by PEN America, there has been a significant rise in educational gag orders and book bans in America in the past two years. Gag orders refer to state legislature restrictions on topics like “race, gender, American history and LGBTQ identities” being taught in schools.

Such restrictions have become law in 16 states, though 306 gag order bills have (so far) been introduced across 45 states. Meanwhile, 32 states (5,049 schools) currently have some form of book banning in place in school libraries. PEN America argues such censorship “imposes ideological control over the freedom to read, learn, and think”.

Conversely, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis claims reports of book banning in Florida are a “leftist hoax”. He argues the “mainstream media, unions and leftist activists” are trying to indoctrinate students, and that books with “pornographic content and other types of violent and age-inappropriate content” have been identified in 23 school districts across Florida.

In response to book banning allegations, he claims “harmful materials” are being removed from Florida schools to ensure students are provided with “a quality education free from sexualization”.

This is echoed by Florida Commissioner of Education, Manny Diaz Jr., who said:

Education is about the pursuit of truth, not woke indoctrination […] Under Governor DeSantis, Florida is committed to rigorous academic content and high standards so that students learn how to think and receive the tools necessary to go forth and make great decisions.

This directly contradicts the argument made by the lawsuit against Escambia County, which states:

Ensuring that students have access to books on a wide range of topics and expressing a diversity of viewpoints supports a core function of public education, preparing students to be thoughtful and engaged citizens.

It appears both sides are fighting against indoctrination – but fundamentally disagree on what it is.

What the research tells us

Representation is vital in children’s literature. Restricting diverse voices and stories is an issue with far-reaching consequences. Research shows that a child’s ability to “see themselves” in books has a wealth of educational and emotional benefits.

It helps connect them to the world, validates their personal experiences, forges positive social connections – and even helps them do better in school.

As the World of Difference Institute explains:

Books are mirrors in which children can see themselves. When they are represented in the literature we read, they can see themselves as valuable and worthy of notice.

Sarah Mokrzycki does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.