For a clear signal that the cost of living is still biting for many, you just need to look at how business is booming at the UK’s largest pawnbroker, H&T. The company recently reported a 12.5% rise in pre-tax profits to £9.9 million for the first half of 2024.

Some media outlets have been quick to link these profits to rising poverty and the cost of living. There are stories of people who have used pawnbrokers out of desperation, parting with beloved jewellery to put money on the meter or to buy food.

From this, pawnbroking is seen by some as a business that attracts those with the tightest finances. H&T Pawnbrokers, for example, charges an annual percentage rate (APR) of up to 165.5% on items pledged to it. When the results were announced, H&T’s chief executive Chris Gillespie said however that the business was continuing to “attract increasing numbers of new and returning customers, for whom alternative sources of small sum regulated lending are much constrained”.

APRs like this are, of course, eye-watering, although nowhere near as high as those of payday loan companies like now-defunct Wonga. These companies were brought under much tighter regulation in 2015 in light of huge public uproar.

These days, the pawnbroking industry is regulated. For example, customers now have the right to withdraw from an agreement within 14 days and pawnbrokers must do their due diligence to ensure that they are not accepting stolen goods.

And it’s important to remember that pawnbrokers can provide people (many of whom have a poor credit rating) with a valuable service, acting as lifesavers for those who need money quickly. As long as people know what they are getting into upfront and have the means to pay the loan back, then it’s arguably a case of no harm, no foul.

A 2018 sector review by the Financial Conduct Authority highlighted a number of positive aspects of pawnshops, including how pawnbrokers offer customers a personalised service as well as flexibility.

Anything that would fetch money

But no matter how well regulated and personable pawnbroking is, the industry has historically been seen to be on shaky moral grounds. This is especially true the further back through history we go. Profiting from people in need is not new, nor are pawnbrokers’ rising profits part of an innovative business model. People with money problems have always been an important market of pawnbrokers.

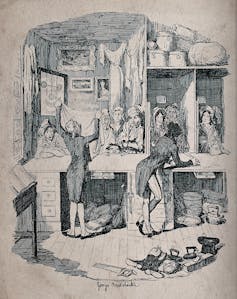

Accounts of poverty during the Georgian and Victorian periods (1714-1901) are full of mentions of people using pawnbrokers. People would pawn their wedding rings as well as their clothing, beds and furniture for the most basic of items.

In 1805, for example, one pauper named Hannah Wall recounted how as a result of her youngest child being sick and needing a doctor, “My cloths are all in the pawn brokers” and “as to my other child, he is almost naked for want of cloths”. The child, unfortunately, did not survive and the mother was left in dire poverty and in desperate need of welfare.

Growing profits for pawnbrokers during downturns in the economy is not new, either. During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars of 1792-1815, unemployment rose and the costs of goods grew at a faster pace than wages.

As such, pawnbrokers benefited. One person commented that during this period, “the pawnbroker’s store-rooms were crowded; families were reduced to the greatest misery, having parted with their beds, furniture, clothes, in fact anything and everything that would fetch money”.

In one particularly heartbreaking story, a former apprentice to a pawnbroker told of a destitute woman who used their services and never regained her possessions:

A poor woman in her need, pawned her gown, petticoat, and stays at our shop, for fifteen pence, and for fourteen years successively payed the interest amounting to two guineas, besides ticket money, but unfortunately for her she could pay the interest no longer, and she had the mortification to see her clothes exposed for public sale.

The 15 pence that this woman received was equivalent to around a day’s pay for a male farm worker. From this, she paid interest of 42 shillings (504 pence), which works out as her paying the 15 pence back to the pawnbroker more than 33 times.

Across thousands of years of history, pawnbrokers have been portrayed as reprehensible figures who were inherently dishonest and often trod outside of legal boundaries to maximise profits. Many were seen to deal in stolen goods and were happy to do over friend or foe in their pursuit of money, offering low returns on the goods pledged to them and charging extortionate interest. These extreme views were often built around antisemitism.

Into the 20th century, things have thankfully gotten better for most. The Liberal welfare reforms of 1906-1914 aimed to tackle poverty by focusing on the old, sick and unemployed. The reforms brought in new support like free school meals, old age pensions, and health and unemployment insurance.

Then the founding of the welfare state after the second world war meant that many more marginalised people became entitled to sick pay and free healthcare through the newly created National Health Service. This further reduced the need for people to go to the pawnshop to raise funds for food or medicine.

But of course poverty has not yet been eradicated. And although pawnbroking is better regulated, we probably should not be surprised to see businesses like H&T doing well as living costs continue to rise.

Joseph Harley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.