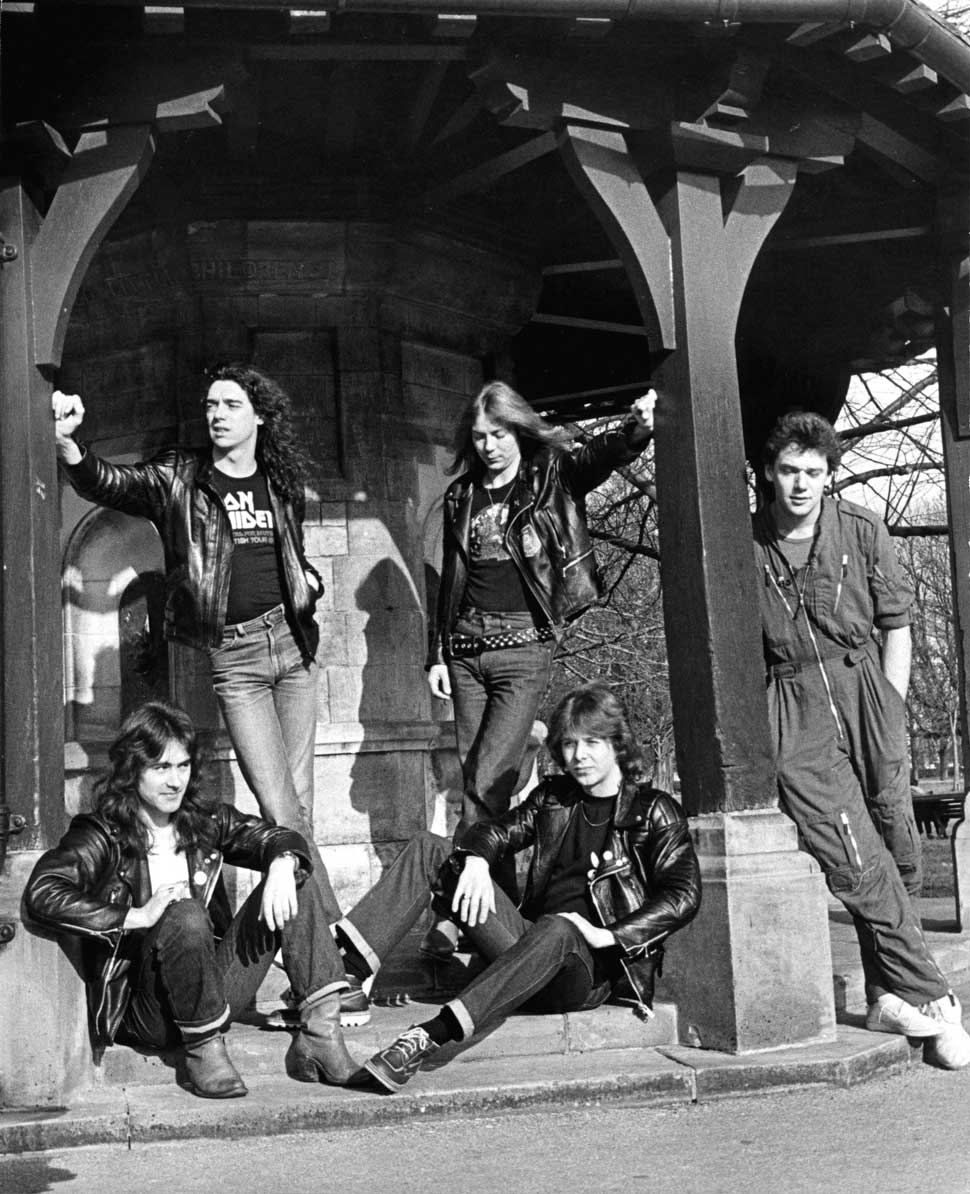

In the first days of 1980, when Iron Maiden entered Kingsway Studios in West London to begin recording their debut album, bassist Steve Harris had mixed emotions. He had a quiet confidence in the strength of the material he had written for the band and he also knew that the band’s new line-up was the best it had ever been, with the addition of a hard-hitting drummer in Clive Burr, and an accomplished guitarist in Dennis Stratton to play alongside Dave Murray. Even so, Harris had, deep down, a sense of nagging fear.

“I suppose I was always worried in the back of my mind that it could all come tumbling down rather quickly,” he later admitted. “You don’t take anything for granted – it’s the old ‘here today, gone tomorrow’ thing. And it’s very much a business that’s like that – more so than most other professions. So you try not to get yourself too worked up, in case it falls flat. That was my attitude.”

For all his pragmatism, Harris was a born leader with a fierce determination to succeed and a single-minded vision for Maiden. As Dave Murray said: “Steve was the nucleus. He gave the band its identity. He was very meticulous and methodical. That’s just how he was, right from the start. And it was fantastic to have that focus with Steve’s songs and ideas and the way he projected them.” It was that focus, and above all, those songs, that would define Iron Maiden’s first album as a classic. The plan was straightforward enough.

“We’d been playing these songs live for a long time,” Harris said. “We knew them inside out. And we wanted to capture in the studio what we did live. I think most first albums are like that. Any band that’s been around a few years, the first album is like a best of those years.” The difficulty was in finding the right producer. One who had worked with the band in late ’79 was Andy Scott, guitarist with glam rockers Sweet, who was relieved of his duties after suggesting that Harris play with a pick instead of his fingers.

“I told him what he could do with that,” Harris said. His preferred option was Martin Birch, producer for Deep Purple – a major influence on Harris – and other rock giants including Rainbow and Whitesnake. But with Birch busy on Black Sabbath’s Heaven And Hell, their first album with singer Ronnie James Dio, the Maiden job went to Wil Malone, who had also worked with Sabbath as conductor and arranger on the albums Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, Sabotage and Never Say Die!

To the band’s irritation, Malone had a laidback approach that bordered on disinterest. “We had problems with the producer,” Harris said. “We used to laugh about him sitting there with his feet up on the desk, smoking a big cigar and reading Country Life – because he didn’t do fuck all else. We’d try to get some feedback off this guy, and he’d just go, ‘Oh, I think you could do better.’ So in the end we would just ignore him. We ended up bypassing him and worked directly with the engineer, Martin Levan. We were still learning then, so thank fuck we had a good engineer who was into it.”

There was also a moment, during the recording of the album’s epic piece Phantom Of The Opera, when Harris sensed that Dennis Stratton, new to the band, might not be the right fit. On a day when the other members were absent from the studio, Stratton took it upon himself to add extra guitar harmonies and backing vocals to the track. Harris was horrified when he heard it. As he recalled: “They played it to me and I went, ‘What the fuck’s that?’ It was like Bohemian Rhapsody gone wrong.”

Stratton later conceded: “It sounded too much like Queen. But that’s me – I get carried away.” He was, he says, “a little upset” when his embellishments were wiped off the track. But he knew the score. This was Steve Harris’s band, and that message was clear to all concerned, their label EMI included. Maiden’s manager Rod Smallwood was a bullish operator who had secured a long-term deal with EMI as the first step towards world domination, but as he said, “The record company never had anything whatsoever to do with the creative vision of Iron Maiden. No one went into the studio, ever. They even kept me out!”

As principal songwriter, Harris was sole author of five of the tracks featured on the album. Prowler was a politically incorrect stalker song full of menace; Transylvania a head-banging instrumental with sizzling interplay from Murray and Stratton; Strange World a subtle, emotive number with sci-fi imagery; Phantom Of The Opera a seven-minute blitzkrieg and an air-guitarist’s dream; Iron Maiden, the tumultuous signature song in which singer Paul Di’Anno delivered the self-fulfilling prophecy: ‘Iron Maiden’s gonna get you, no matter how far’.

Two tracks were co-written by Harris and Di’Anno: Running Free, the album’s anthem, inspired by the singer’s juvenile delinquency as an East End skinhead; and Remember Tomorrow, a deep heavy metal ballad which had for Di’Anno “a special meaning”, its title derived from a favourite phrase of his grandfather’s. And there was one song written by Dave Murray, a sleazy tribute to a Cockney hooker, named Charlotte The Harlot. “A great song!” Murray said. “Great title too.” Although he added, somewhat unconvincingly, “I can’t remember where the lyrics came from.”

As Harris later said, “We did hold some songs back, I must admit.” Among them were two staples of the band’s live set, Sanctuary and Wrathchild, both of which had been selected for a New Wave Of British Heavy Metal compilation album that EMI would release in February 1980, titled Metal For Muthas. There was also a feeling within the group that their album, despite Martin Levan’s best efforts, sounded a little undercooked.

“None of us were happy with the production,” Harris said. “It just didn’t sound as ferocious as we did when we played live. It didn’t have enough of the fire and the bite and the anger that we had in our playing.” But as he also recalled, “We knew we’d made a strong album. It had really good songs and loads of attitude. And as a singer, Paul had real charisma. It was still a good album. Really good.”

It was more than that. Recorded for the meagre sum £12,000, Iron Maiden’s debut turned out to be one of the greatest and most influential heavy metal albums of all time, a touchstone for Metallica and so many others that followed.

Iron Maiden were in Bristol, to play at a grubby little joint, fancifully named Romeo & Juliet’s, on February 6, 1980 – the day when a damning review of the Metal For Muthas album appeared in a new issue of Sounds. It was just a few days after they finished recording at Kingsway that Maiden had begun the Metal For Muthas tour, headlining, with support from another young London-based band, Praying Mantis. Sounds writer Geoff Barton, who had done so much to promote the NWOBHM, pulled no punches in his assessment of the Muthas album, dismissing it as “a joke” and “a low-budget cash-in on the UK’s much-vaunted metallic revival”.

His complaints centred on weak recordings of tracks by promising bands such as Praying Mantis and Sledgehammer, and the inclusion of some lame acts, including the daftly named Toad The Wet Sprocket. But he praised the two Iron Maiden songs, Wrathchild and Sanctuary, as “raucous HM/ punk crossovers and tantalizing tasters for their own forthcoming LP.” And his conclusion – hailing Maiden as the NWOBHM’s leading power – was on the money. “The more I think about it, the more I reckon that the ‘guv’nors’ crown now rests on their collective Cockney heads.”

For Maiden, the timing of the NWOBHM had been fortuitous. As Harris said: “It was obvious that something big was happening, and that was great for us, being right in the thick of it.” But he added, in typically straight-talking fashion: “I never really paid much attention to whatever else was going on. It’s not that we didn’t care about other bands or anything like that. Some bands we knew as friends and we hoped they all did well. But we never thought about what everyone was doing. We just got on with our own thing.”

In the last week of February, Running Free was released as Iron Maiden’s debut single. The cover art portrayed a sinister figure, lurking in a dark alley and brandishing a broken bottle as a longhaired rock fan ran for his life. The big reveal would come with the album cover. Ahead of that, Running Free blasted into the UK chart at No. 34 on the UK chart, leading to an appearance on Top Of The Pops. The band made a statement by refusing to mime to the track, as was standard for the show. Instead they performed live, the first group to do so on TOTP since The Who in 1972.

“Everybody used to slag off Top Of The Pops,” Harris said, “but for a metal band to get on there was a big thing at the time. It was fantastic that we were on there mixed in with all this pop stuff. And of course my mum hated it, which was great.”

It was followed by a major UK tour, opening for Judas Priest in 3000-capacity theatres. In many respects it was a perfect match – Priest the established masters of British metal, Maiden the young pretenders with a similar style and twin-guitar attack. But in the build-up to the tour, Di’Anno had cockily proclaimed to Sounds’ Garry Bushell that Maiden would “blow the bollocks off Priest”. As a result, the tour played out in an atmosphere of simmering tension, with allegations of Priest’s road crew sabotaging Maiden’s sound. Di’Anno’s boasting alienated some Priest fans. Many others were won over by Maiden’s live prowess. And in a strange coincidence, a week after the tour ended, the Iron Maiden album, self-titled, and Priest’s British Steel, were released on the same day, April 14.

In the two, there was much common ground: classically styled heavy metal power, duelling guitars, and bare-bones production. Di’Anno’s singing was at times reminiscent of Priest’s Rob Halford, and in Remember Tomorrow there were echoes of the Priest classic Beyond The Realms Of Death. And just as the cover of British Steel would become iconic – a razor blade stamped with the band’s logo – so the artwork for Iron Maiden would burn an image into the consciousness of metal fans all over the world.

Illustrator Derek Riggs knew nothing of Iron Maiden when he painted a skeletal, wild-haired bogeyman on a lamp-lit city street. Riggs had thought the image might work for a punk band. But when Rod Smallwood came across this illustration, purely by chance, he immediately realized that it was a perfect embodiment of Maiden’s trusty horror-mask stage prop.

“There was Eddie,” Smallwood recalled. “It was like he’d been done just for the band.” Only one small alteration was required – the lengthening of the figure’s hair to align it with heavy metal, not punk. This vision of Eddie was so powerful that one young metal fan from Brazil, Max Cavalera, later the frontman for Sepultura, bought the album on the strength of the cover alone, having never heard a note of Maiden’s music. “And when I played it,” Cavalera said, “it fucking killed me.”

The album received a rave review in Sounds from Geoff Barton. “Heavy metal for the 80s,” he wrote, “its blinding speed and rampant ferocity making most plastic heavy rock tracks from the 60s and 70s sound sloth-like and funeral-dirgey by comparison.” Steve Harris might have baulked at Barton’s continued references to a punk sensibility in Maiden: “A safety-pin/loon-pant hybrid? In many ways, yes!” But that review played its part in what happened next – when this album, exceeding all expectations, entered the UK chart at No.4. For the levelheaded Harris, it was a shock. “I really couldn’t believe it,” he said. “It was like we’d fulfilled our dreams right away.”

In the wake of this triumph, Maiden hit the road again, headlining in many of the same theatres in which they had opened for Priest. It was a marathon 45-date tour with Praying Mantis again as support, and in the midst of it came another single – a new version of Sanctuary, different to that on the Metal For Muthas album, with a cover by Derek Riggs picturing Eddie caught in the act of killing British Prime Minster Margaret Thatcher: in her dead hand, an Iron Maiden poster torn from a wall, in his, a long knife dripping with her blood. The resulting controversy led to a story in The Daily Mirror with the headline: IT’S MURDER! MAGGIE GETS ROCK MUGGING! The Sanctuary single did even better than Running Free, peaking at No.29.

The band’s heavy touring schedule was “testing”, as Murray put it. “You’re in confined spaces,” he said. “The tour bus, the dressing room. You live and breathe with each other, day in, day out, and that can be tough.” But as Smallwood said of Maiden’s global strategy: “We wanted to do big things in Europe and America. Some bands were huge in Britain but meant nothing elsewhere. We were looking at the whole world.” And at the end of August – following an appearance at the Reading Festival as guests to a band that Harris much admired, UFO – Maiden embarked on their first European tour, opening for Kiss.

It was Kiss bassist Gene Simmons who picked Maiden for this tour. He told Smallwood: “Iron Maiden is going to take over from Kiss as the biggest merchandising band in America.” And as he later elaborated: “Maiden immediately struck me as a band with huge potential. The band was both musical and powerful, and being the capitalist pig that I am, Eddie struck me as an iconic visual that would buy everybody in the band big houses.”

Over 24 dates, Maiden played to more than 350,000 people, and it was during this tour that Paul Di’Anno had a moment he would remember for the rest of his life. “I saw Gene Simmons – one of the richest and most famous rock stars in the Western world – wearing a fucking Iron Maiden t-shirt,” he said. “That was when I realized the world had finally gone mad.” But for Dennis Stratton, the end of the road was near.

As Smallwood saw it, Stratton was always a square peg in a round hole. “Dennis liked the Eagles,” he said, “and wore red strides and a floppy white top. Sadly, he just wasn’t very metal.” Stratton’s last act with Maiden was the recording of a one-off single, Women In Uniform, a cover of a corny number by Australian band Skyhooks. When the single was released in November, to coincide with the final UK leg of the tour, Stratton had been fired. His replacement was Adrian Smith, an old friend of Dave Murray’s.

“Adrian and I were in a band together, way back,” Murray said. “Before I joined Maiden in ’75.” With Smith broken in on that tour, the band promptly set to work on their second album. And this time, they had the producer that Steve Harris had wanted all along.

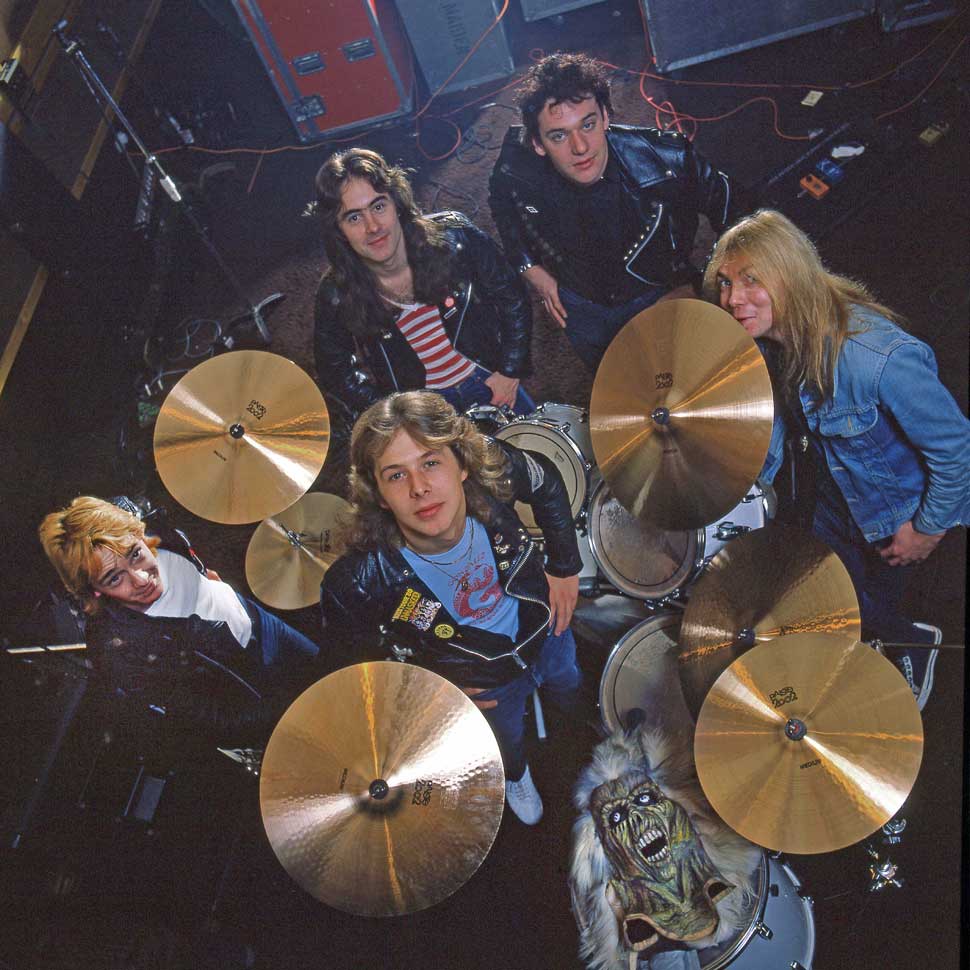

According to Dave Murray, the second album, Killers, was “the real turning point” for Iron Maiden. “I think the band really kicked on from the first album,” he said, “and a big part of that was having Martin Birch as our producer. We were all big fans of Martin’s work with Deep Purple. We also loved what he did with Black Sabbath on Heaven And Hell, so for Martin to come on board for Killers was fantastic. He brought something new to our sound. On the first album we were playing fast, almost like punk rock, but with more melody. Martin’s production on Killers gave us a little more polish, without losing our edge. The whole album was really powerful and atmospheric, and it was Martin Birch who brought that out of us.”

Killers was recorded in December 1980 at London’s Battery Studios. Harris said: “Just like the first album, we had a lot of songs that we’d been playing live. I only had to write three new ones.” The album featured ten songs: nine written by Harris alone, the title track by Harris and Di’Anno. The latter was a heavy drama with grisly lyrics and a dominant performance from the singer. As Murray said: “Paul sounded great on Killers, and that song had such a pure and raw energy.”

Wrathchild had a dark intensity and an irresistible force, this new version, sharply focused by Birch, so much heavier than the Metal For Muthas cut. There was blazing energy in Another Life, Innocent Exile, Purgatory and Drifter, and an epic feel to the instrumental Genghis Khan. And in the three newly written tracks, there was a second instrumental piece, The Ides Of March, to serve as the album’s grandiose intro; a semi-acoustic number, Prodigal Son, to add a different texture; and a spiritual heir to Phantom Of The Opera in the blood and thunder of the Edgar Allen Poe-inspired Murders In The Rue Morgue.

What Derek Riggs created for the cover of Killers was fittingly gruesome, with Eddie as an axe-wielding maniac grinning with pleasure as his victim falls. In the background, an East End street scene, featuring a sex shop, the figure of Charlotte The Harlot lit in red in a window above, and the Ruskin Arms, the pub where many early Maiden gigs were staged.

Ironically, given its cover, Killers was the subject of a hatchet job by Sounds critic Robbi Millar, who slammed the album as “a failure” and described much of its contents as “well dodgy”. The only positive review came from Malcolm Dome in Record Mirror. But as Harris said: “We knew it was a bloody good album.”

When Killers was released on February 29, 1981, the band had already begun a UK tour, the first phase of a worldwide campaign that would stretch to 113 dates. Killers reached No. 12 in the UK, eight places lower than the first album’s peak position. But as the tour progressed, sales of Killers eventually passed 750,000, more than double that of the debut, with 150,000 units shifted in America.

“It was all about touring,” Adrian Smith said. “Honest hard work. It wasn’t about going for the big commercial album. We did what we did. And a lot of that was down to Steve leading the band. He’s very straight ahead.”

On the UK tour, Maiden’s support act was Trust, the French punk-metal band that had been championed by AC/DC singer Bon Scott, and featured a young, flat-nosed British drummer by the name of Nicko McBrain. It was when Maiden ventured into Europe in May that the first signs of trouble came. Paul Di’Anno had always had a taste for the rock’n’roll lifestyle, and after he blew out his voice due to excessive partying, several gigs in Germany were cancelled.

“Paul was a larger-than-life character,” Harris said. “He was an important part of the band, and on the surface of it, what people could see, it was working well with Paul. But we had this rule: people have to remember what they’re there for. We never cared what they did anywhere else, as long as they did their gig. And Paul was getting totally fucked up.” Di’Anno admitted as much: “It wasn’t just that I was snorting a bit of coke,” he said. “I was going for it non-stop, 24 hours a day.”

The simple fact was that Iron Maiden could not carry passengers. Touring was key to the band’s development. And while Di’Anno managed to keep it together for another three months – through dates in the Far East, where the live EP Maiden Japan was recorded, and in North America, where the band opened again for Judas Priest – it was clear to Harris that a tough decision had to be made.

“Paul was given chances,” he said. “He was read the riot act, and given the chance to put things right. But he didn’t put things right. And we knew that if we didn’t do something we’d go downhill pretty sharply and that would be the end of it.”

When the band returned to Europe in August, Harris and Smallwood attended the Reading Festival to watch NWOBHM group Samson and meet with their singer. Bruce Dickinson had first seen Iron Maiden play live in May 1979 when they supported Samson at the Music Machine club in London. “It was blindingly obvious,” he said, “that Maiden were going to be massive. This hyper-kinetic band, it was really a force of nature. And Paul Di’Anno, he was okay, but I thought, ‘I could really do something with that band!’” A few days after his meeting with Harris and Smallwood at Reading, Dickinson auditioned in secret for Maiden, before the band set out with Di’Anno for the last run of European shows.

According to Di’Anno, the catalyst for his exit from the band was the death in 1981 of his grandfather, the man who had inspired Remember Tomorrow. “After losing my grandad,” he said, “being in a rock band just didn’t seem so important anymore.” Di’Anno’s final show as the singer for Iron Maiden was in Copenhagen on September 10, 1981. The matter was resolved in a meeting with the band and Rod Smallwood. “It was a civilized discussion,” Di’Anno recalled. “It was literally a case of Rod saying, ‘Paul, we think it’s best if you leave Maiden,’ and me saying, ‘That’s alright, I was going to resign anyway.’”

Harris was sad that it had come to this. “I didn’t like doing what I had to do,” he said. “We were all gutted to lose Paul, and we tried hard to keep him in the band, but he didn’t try hard enough himself.” He also understood what a gamble this was. “Changing a singer is a massive thing for any band. And we’d done well with the first two albums. We knew we didn’t have any choice but to make the change, but you don’t know what’s going to happen next.”

Iron Maiden had come so far in such a short space of time, and yet, in September 1981, as they waited to announce Bruce Dickinson as the band’s new singer, Steve Harris was in one sense back where he was in January 1980 – a worried man. “No matter how good Bruce was, there was no guarantee that Maiden fans were going to take to him,” he said. “It was a very, very worrying time. We knew Bruce was good, but he was very different to Paul. So you’re thinking, are people going to accept this?” As it turned out, Harris had the answer to that question, and it was quite simple. “I just thought, well, they’ll have to!”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 267 (October 2019)