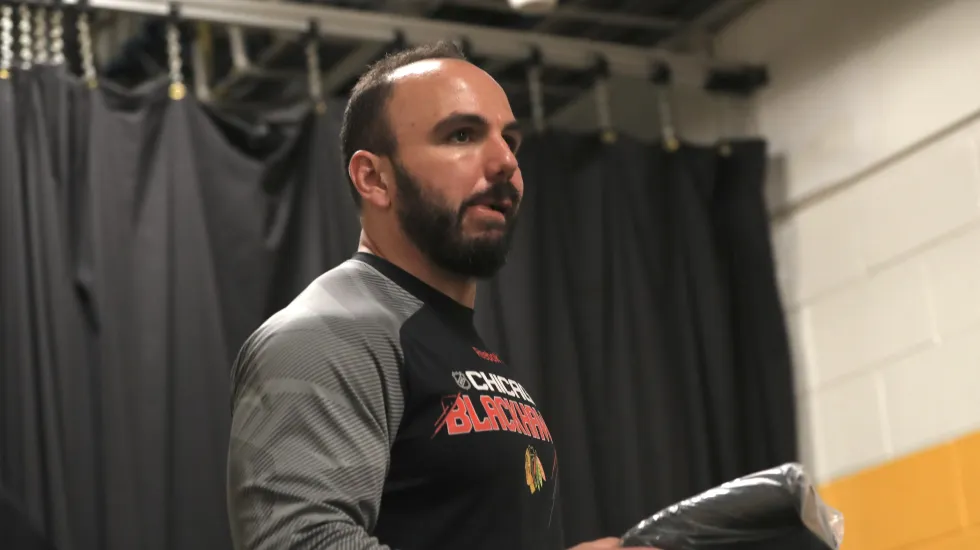

When defenseman Connor Murphy arrived in 2017 for his first session with Paul Goodman, the Blackhawks’ head strength-and-conditioning coach, the first things he noticed were Goodman’s feet.

‘‘He was barefoot the majority of the day — all day, if he could be,’’ Murphy said, grinning. ‘‘If he could be barefoot outside the rink, he would.’’

Five years later, whenever he’s around Goodman, Murphy is now barefoot, too.

‘‘Then he started getting the balance beams out,’’ Murphy said. ‘‘You’ve got a bunch of awkward hockey players jumping around, balancing on balance beams. It looks funny. It’s different than what you’d expect the traditional athlete to be doing: lifting heavy weights, doing heavy squats. [Instead], we’re doing mobility and balance work. But that stuff has paid dividends for a lot of us.’’

For 14 years now, Goodman’s unique approach to training — focusing on the mind as much as the body and emphasizing interpersonal connections as much as muscular strength — has given the Hawks a literal leg up on the competition.

And Sunday against the Stars, Goodman quietly will work his 1,000th NHL game.

It won’t receive nearly the fanfare that captain Jonathan Toews’ 1,000th game did last weekend, and Goodman, whose whole career has taken place behind the scenes, doesn’t mind that. But it’ll be just as impressive.

‘‘The guys respect him,’’ Hawks interim coach Derek King said. ‘‘He doesn’t have to drag guys up there to the workout facility. They want to go.’’

‘It’s about flow’

As a ‘‘one-man show’’ running the University of Vermont’s strength-and-conditioning program in the mid-2000s, Goodman ‘‘singlehandedly built a culture where the players were willing to sacrifice more and take [training] a heck of a lot more seriously,’’ former Vermont hockey coach Kevin Sneddon said.

After moving on to the Hawks in 2008, Goodman quickly realized he was dealing with a new beast.

‘‘When I was at Vermont, directing the program there, I had 19 varsity sports,’’ Goodman said. ‘‘People are like, ‘You must be so happy you only have to work with one team.’ I’m like, ‘No, these [players] are like 23 different sports.’ They all have their own intent, interests and methodologies.’’

Space was another issue.

At The Edge in Bensenville, the Hawks’ practice facility at the time, he would walk into his cramped, out-of-date training room every day and mutter, ‘‘This is never going to work.’’

At Johnny’s IceHouse, their next practice headquarters, he couldn’t fit more than four players in his closet-like space without bumping shoulders.

Now at Fifth Third Arena, Goodman’s dojo is more like a presidential suite. It occupies much of the second floor, far bigger than necessary for the exercise equipment that lines the mirrored walls.

‘‘I really like empty space because I can build a session out and take it all down, and the next day can be a whole different session,’’ he said. ‘‘For me it’s about flow, and this space is inviting and what I envisioned when we built it.’’

Relationship-builder

Goodman challenges himself to strengthen the Hawks not only physically but also emotionally, building up their confidence and resilience as much as their muscles and balance.

‘‘You can do all the prep you want, but if you’re out there [without] toughness, mental performance and leadership, then you’re probably not going to be effective,’’ he said.

Goodman uses the word ‘‘camaraderie’’ often. It’s what allows players to feel as though they’re working with him to improve, rather than he’s working to improve them.

His coaching style differs for every player, based on how they learn best. And with so many players coming and going every year, that requires tremendous versatility. Consider as proof the fact that quiet, introverted David Kampf finished first in the Hawks’ training-camp fitness testing last season and assertive, outgoing Murphy finished first this season.

‘‘[Paul is] really into giving you what you need at the right times,’’ Murphy said. ‘‘He’s a guy I can go to and ask what I need that day, and he’ll tell me. And he’s pretty much always right.

‘‘Then on top of that, he’s a fun guy that doesn’t take himself too seriously and is super-humble for how many accomplishments he has had and places he has been. That combination makes him a great resource for us.’’

The pandemic tested Goodman’s approach, but he prevailed by pivoting to hosting Zoom workouts for Hawks players scattered across the world. The Hawks’ imminent rebuild — which will throw many young, inexperienced prospects his way — will test it, too, but he’s undaunted.

‘‘I don’t know who [the newcomers are] going to be, but I do know I’m going to care about their development,’’ he said. ‘‘Because if they’re successful here, they’re more likely to be successful out there, which leads to the team being successful.’’

Winning desire

By Goodman’s second season, 2009-10, he could tell his players were maturing, trusting him and buying into his lessons.

‘‘[It was] like watching us become great,’’ he said.

After hoisting the Stanley Cup at the end of the season, he remembers telling his dad, ‘‘I want to do that again.’’

He got to do it again — twice. But he simultaneously has learned how to handle the bitterness of defeat, given that he can’t skate onto the ice and influence the outcomes of games himself.

‘‘It’s sometimes very frustrating because you want to be able to contribute,’’ he said. ‘‘But you have to take a step back and know the guys are ready [and] prepared to do what they need to do.

‘‘My vision of this position is you have to be static. [You have to be] positive and uplifting for guys, but they’re going to go up and down — a win is great, a loss is terrible. If you’re not [static] and you go up and down with them, then there’s no rope they can hang on and say, ‘OK, at least he’s going to be able to help me.’ ’’

Goodman credits his wife, Susan, and Mike Gapski, the Hawks’ head trainer for 35 years — among many others — for helping him through it all.

His career has diversified through the years, too. He’s pursuing a Ph.D. in sports science at the Auckland University of Technology, and he owns and directs his own company, Goodman Elite Training.

But the Hawks, of course, remain his top priority. And as he crosses the 1,000-game milestone, the inevitability of a few lean years ahead hasn’t diminished his drive whatsoever.

‘‘We’re all building this thing back up, and it’d be really gratifying to be there when we win again,’’ he said. ‘‘It’s not a question in my mind we’re going to win again. And I want to be there for it.’’