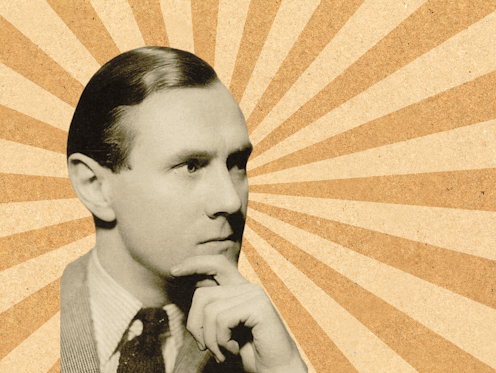

Did you know that 2023 marks the 50th anniversary of Patrick White winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first Australian writer to be so honoured?

Until last week, neither did I. Nor did many of my fellow academics. As a lover of White’s writing, I was shocked by my own lack of awareness, which was quickly overshadowed by the realisation that seemingly everyone had overlooked it. Surely someone must have commented?

As far as I have been able to find, there has been one article back in autumn by Barnaby Smith in the NSW State Library’s magazine Openbook and few Twitter posts similarly aghast at the neglect.

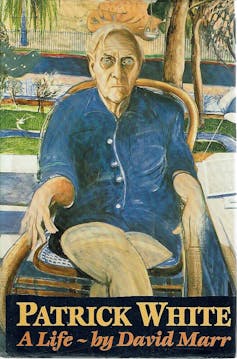

By contrast, you are more than likely aware that this October marks the 50th anniversary of the Sydney Opera House, officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II two days after the announcement of White’s award. As David Marr recounts in his biography of White, when the photographers crowding around White’s house were asked if they could come back in the morning, they replied: “We have to do the Queen in the morning.”

Cultural cringe

When I first began thinking about writing this piece, I was motivated by a sense of frustration that White – and Australian literature more generally – was again being neglected.

My first thought could be summarised as follows: “How dare they forget him! There should have been conferences and celebrations – a festival that would leave the Opera House in the dust! Imagine the furore if Ireland had forgotten Beckett’s 50th anniversary in 2019! What a contemptuous place this is that can neglect an important occasion for one of its greatest writers!”

Previous anniversaries had received significant attention. The 50th anniversary of White’s best-known novel Voss in 2007 was marked with a two-day symposium. The centenary of his birth in 2012 was likewise acknowledged with conferences in Australia and various international locations.

What was different about this anniversary?

Despite my anger, should I really have been that surprised? Last semester, I had quizzed my first year Literary Studies students to see if anyone knew who our first Nobel laureate in literature was.

Silence.

When I told them, no one had heard of Patrick White, let alone read him.

The same goes for Miles Franklin (both the author and the prize), Christina Stead and Joseph Furphy, just to name the canonical writers I thought they might have known. Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson were the only two to receive a reprieve.

Contemporary Australian authors didn’t fare much better. When I asked them why they didn’t read much Australian literature, the most frequent answer – usually tempered with laughter – was: “Well, I guess it’s just not very good, is it?”

Here is the opportune time to introduce the impossible to avoid concept of the “cultural cringe”, the term coined by A.A. Phillips in 1950. The cringe, Phillips wrote,

mainly appears in an inability to escape needless comparisons. The Australian reader, more or less consciously, hedges and hesitates, asking himself ‘Yes, but what would a cultivated Englishman think of this?’

When it comes to White’s reception, especially post-Nobel, the cringe is everywhere apparent. It was fostered by the prize citation itself. For the Nobel committee, White was worthy of the prize because he had created an “epic and psychological narrative art which has introduced a new continent into literature”.

As many people have highlighted, White’s Nobel was a watershed moment of international recognition for Australian literature. It would be followed by Thomas Keneally winning the Booker Prize in 1982 for Schindler’s Ark and Peter Carey winning of the same award in 1988 for Oscar and Lucinda.

Here were signs, at last, that Australians could produce real literature – at least, according to Europe and Britain.

A writer unread?

White’s relationship to Australian literature was always shaky, if not outright venomous. He infamously chastised mainstream Australian writing as little more than the “dreary dun-coloured offspring of journalistic realism”.

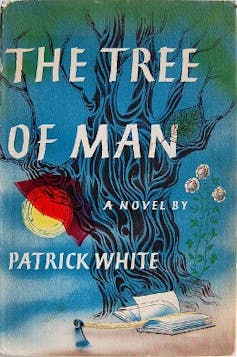

Many Australian readers were happy to return the favour. His local critical reception was often uncomprehending, and at times hostile. A.D. Hope’s similarly infamous review of The Tree of Man judged the novel to be “pretentious and illiterate verbal sludge”.

White’s uneven reception reflected an anxiety about what Australian literature actually was. This is still a live issue in literary studies. The preeminent questions asked in undergraduate Australian literature units are still: What is Australian literature? What counts as Australian literature? What is the writer’s relationship to the “nation”?

But these questions are today asked within the context of ever-diminishing Australian literature programs at universities, where you will be lucky to find one that offers more than one unit about it, and sometimes not even that. On these grounds, one could easily conclude that White’s star has diminished. Madeleine Watts, in her 2019 article, appropriately titled On Patrick White, Australia’s Great Unread Novelist, would certainly agree.

Christos Tsiolkas makes a similar argument in his 2018 book on White for Black Inc.’s “Writers on Writers” series. He reflects that his desire to write the book emerged out of a “sense of pissed-offness” at not having been made to engage with White earlier by “my tutors, my fellow writers and our critics”.

That Watts and Tsiolkas are both novelists themselves might explain their fervour for White, a writer who fits well under the moniker a “writer’s writer”. And yet White’s reputation has always been tied up with the myth of him being a great “unread” novelist. Watts herself quotes a letter White wrote in 1981, in the last decade of his life, in which he declared:

I’m a dated novelist, whom hardly anyone reads, or if they do, most of them don’t understand what I am on about.

This is not even close to the only time White voiced such frustrations. They are littered throughout his letters and documented in David Marr’s biography. Equally, one of the clichéd tenets of White scholarship has been an attempt to figure out whether we should continue to read him or not – as if this were really the fundamental question on everyone’s mind.

So many of our contemporary discussions about literature – when we remember to have them – constellate around issues that are really at the service of generating discourse about “literature”, rather than genuine criticism and engagement with its artistic qualities.

I’m drawn to these debates as much as anyone. The questions of why literature matters and what makes it meaningful should be discussed frequently. They are some of the most interesting questions we can ask. But the problem with these discussions, and the perpetual crisis of the humanities and literature that we hear about so much, is that they distract us from what is actually meaningful about literature: reading it.

Read more: Homemade and cosmopolitan, the idiosyncratic writing of Gerald Murnane continues to attract devotees

Reputation

When I set out to the write this piece, I wanted to follow through on my anger. I wanted to claim that it was a scandal White had been forgotten by our cultural institutions, that it was a sign of our degraded cultural state. But the more I have thought about it, the more I have been drawn to the idea that maybe, just maybe, this is the best thing that could happen to White and Australian literary culture more broadly.

Ever since he won the Nobel prize, White has been unable to escape the institutional framing of his work, whether he is being critiqued negatively or positively. The question that is asked of White is not just “should we read him”, but should we study him. He has been bound up in cultural debates that may never cease.

White’s reputation as a canonical writer, and more specifically as a “difficult” modernist author and a “writer’s writer”, is a disaster when it comes to getting people, including students, to actually read him. He is not only the kind of writer one would expect to study at school and university; many people assume he can only be read in those contexts.

Of course, White is a difficult writer, though it is often overlooked that he can also be funny, especially in his depictions of suburbia. A favourite scene is this one in The Cockatoos, describing an existential choice familiar to every Australian:

Olive Davoren fell asleep, a pillow-end between shoulder and cheek, like a violin.

She had noticed seed at Woolworths and Coles; it was only a matter of choosing.

One of the birds was pecking at her womb. He rejected it as though finding a husk.

What has never been in doubt is the beauty and sensuality of White’s writing. When reading him, I often feel like Laura Trevelyan in Voss, listening to the eponymous German explorer:

She did not raise her head for those the German spoke, but heard them fall, and loved their shape. So far departed from the rational level to which she had determined to adhere, her own thoughts were grown obscure, even natural. She did not care. It was lovely. She would have liked to sit upon a rock and listen to words, not of any man, but detached, mysterious, poetic words that she alone would interpret through some sense inherited from sleep. Herself disembodied. Air joining air experiences a voluptuousness no less intense because imperceptible.

The more we can learn to read White in this spirit – absolving our rational forms of scholarly detachment, just a bit – the more we might be able to read him as it has always been possible to read him: listening to the shape of his words, their voluptuousness.

Imagine, perverse as this may sound, if White never won the Nobel prize? Could it be possible that the reading of his work would be in a better place today? At the very least, we wouldn’t have nearly as much of the “pretentious and illiterate verbal sludge” – to borrow a phrase – that is obsessed with the discourse around White, rather than his actual works.

Literary prizes, as Beth Driscoll has highlighted, have become an essential part of literary culture. They provide many benefits for winning writers. The domestic and international sales of White’s books greatly increased in the years after he won the Nobel. If he had never won, it’s perfectly conceivable that his work would now be out-of-print.

But the aura of a prize shines briefly. Sometimes it might fade after a week, a year, sometimes 50. But it will fade. What remains is the work itself.

Immediately after the Nobel Prize announcement in 1973, White was interviewed on television by Mike Carlton. Asked whether the prize was a “crowning achievement”, White responded:

I hope my books are the crowning achievement of my career, not awards. But perhaps that is vain.

Vain or not, it would seem, maybe until now, that the award has been the crowning achievement. In light of the neglect of its 50th anniversary, maybe we can start to read White again – read him as aesthetically-minded individuals, not as institutions.

Reuben Mackey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.