Leading up to the 2023 Super Bowl, one of the biggest points of discussion has been the right ankle of Patrick Mahomes. During a playoff game against the Jacksonville Jaguars on Jan. 21, 2023, Mahomes, the quarterback for the Kansas City Chiefs, awkwardly fell on his ankle after being tackled. Mahomes finished the game after trainers taped the ankle up, but after the game, news broke that he’d suffered a high ankle sprain.

As a surgeon who specializes in sport ankle injuries – and having myself sustained a similar injury while playing high school football – I cringed when I saw Mahomes go down during the game against the Jaguars. Ankle injuries are serious affairs. High ankle sprains are painful and can limit performance, but given the level of fitness of an NFL quarterback like Mahomes and the elite-level treatment and rehabilitation teams provide to help players recover, I expect he will be ready to play at Super Bowl kickoff and the injury will cause few if any problems during the game.

What is an ankle sprain?

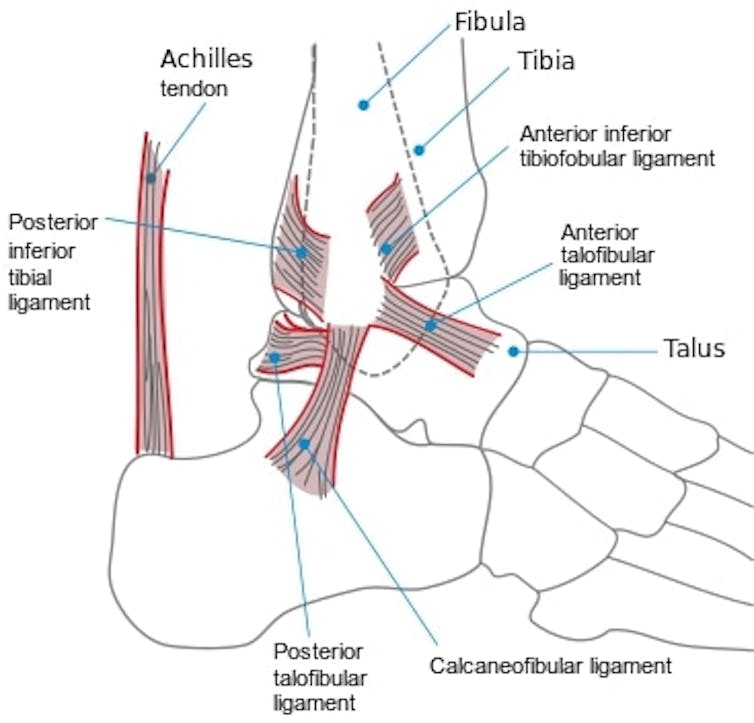

The ankle is comprised of two large leg bones – the tibia, or shin bone, and the smaller fibula, which sits outside the tibia – and a number of strong ligaments that attach the leg bones to the foot and stabilize the whole area.

An ankle sprain occurs when someone abnormally bends or rolls their ankle joint, leading to the stretching or tearing of the ligaments that hold the ankle together. Ankle sprains can be either “low” or “high” based on the location of the affected ligaments and are graded on a scale from one to three – mild, moderate or severe.

The most common type of ankle sprain involves ligaments of the lower, outside part of ankle joint. Low ankle sprains usually occur due to an inversion, or when the outside edge of the foot rolls inward toward the sole of the foot.

High ankle sprains, like the injury Mahomes suffered, are rarer than low ankle sprains and are caused by the opposite motion. When a defensive player for the Jaguars tackled and fell on Mahomes, the defensive player landed on Mahomes’ leg, causing the inside of his foot to roll outward toward the small toe. This motion is what stressed his high ankle ligaments.

Walking it off or needing surgery

Most sprained ankles will result in some level of pain, swelling and difficulty walking on the affected joint — all things that would affect Mahomes’ ability to play comfortably and at the level needed to bring home the Lombardi Trophy. But there is a huge difference between a minor, grade I sprain or a severe grade III sprain in terms of performance and recovery time.

The ligaments of a healthy high ankle provide more stability than the lower ligaments, so high ankle sprains are often more serious injuries. In a bad high ankle sprain, the majority of the ligaments tear completely, resulting in severe pain, swelling and often bruising of the ankle. Initially it is very difficult to even stand on the ankle, let alone run or jump. If not properly treated, the injury can lead to instability, weakness and pain that limits function, especially for an elite athlete.

Based on the video of the injury and my experience treating professional athletes, it looks like Mahomes suffered at minimum a grade II, or moderate, sprain. After a grade II sprain, most people need a period of rest and treatment to reduce the inflammation of the ankle. Resting from running and jumping is important in the immediate days following the injury. If an athlete is able to return to play in the same game or soon after, that is usually a good sign.

Treating high ankle sprains

Generally, high ankle sprains take longer to heal and recover from than other types of sprains, but treatment can help speed up this process.

When a patient comes in complaining of a rolled ankle, I start with a physical exam to check the stability of the joint. If the ankle is stable and the patient can run and jump with little pain, that usually means they have a low-grade injury and will not require much time away from sports. With a bit of rest, most people are back at their activities within a few days.

For more serious injuries, it is first essential to reduce the pain and swelling through a routine of rest, ice, compression and elevation, the well-known “RICE” method. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen can help reduce pain as well. In cases where the ankle is moderately unstable, research shows that providing patients with a boot to immobilize the ankle can speed up the healing process.

I also recommend that my patients stay off the injured leg for a couple of days. After those first days of rest, most patients, and especially elite athletes, can begin putting weight on the ankle with the boot still on. After about four to seven days, I will begin to transition my patients into strength and stability training with a focus on reducing swelling. This will usually include low-impact training such as stationary bike and pool therapy. Gradual return to sport-specific drills occurs prior to return-to-play.

In the most severe cases of grade III high ankle sprains, the ligaments can be torn completely or injured to the point that they are unlikely to heal in a way that supports the ankle. In these cases, surgery involving screws, plates and other hardware to hold the fibula and tibia together can be the best option.

Thankfully for Mahomes and football fans across the U.S., his injury does not appear to require surgery, at least not immediately.

Research shows that most athletes with high ankle sprains often return to their sports and can play at a similar level to how they played before their injury. While Mahomes may not be at 100%, given the moderate severity of the injury, his fitness and the high quality of care he is receiving, I expect that he will be ready to play an exciting game come kickoff on Super Bowl Sunday.

MaCalus V. Hogan is affiliated with American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery,and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine; Hall of Fame Health Medical Advisory Board

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.