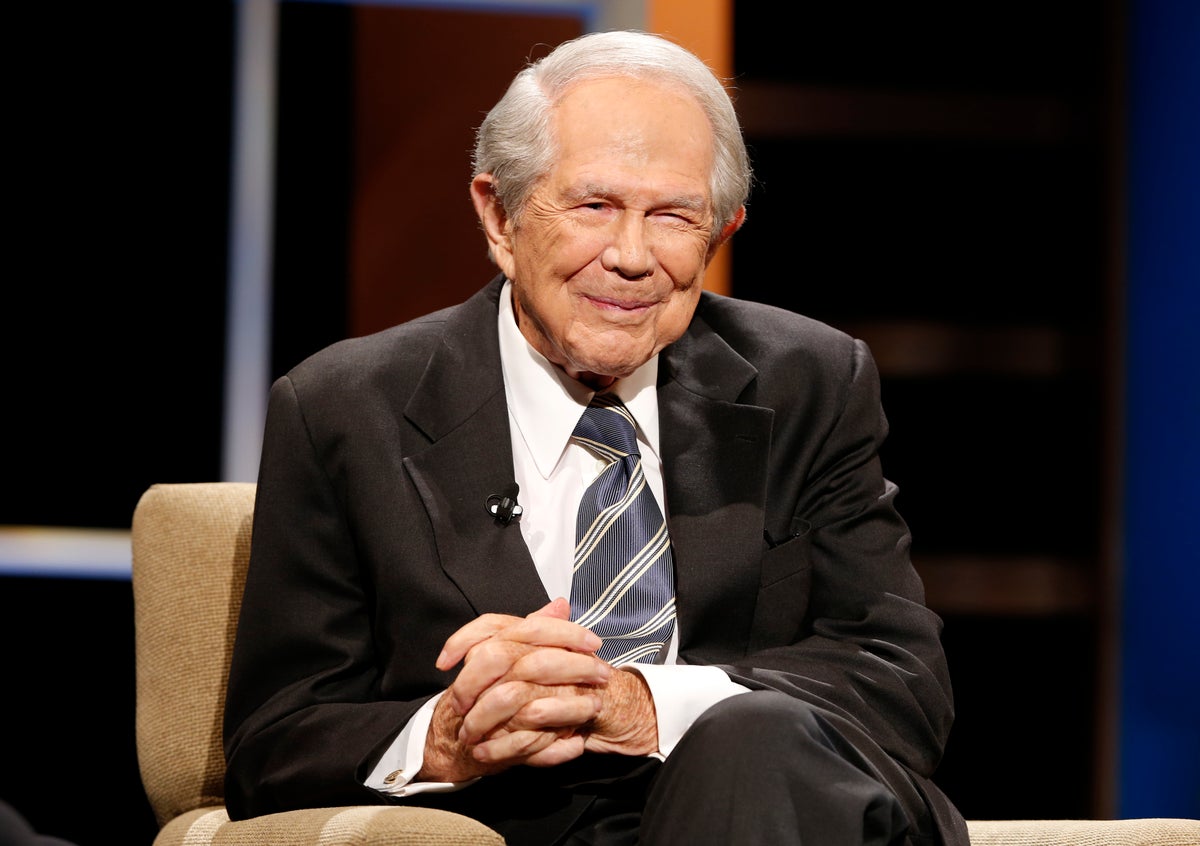

Pat Robertson united tens of millions of evangelical Christians through the power of television and pushed them in a far more conservative direction with the personal touch of a folksy minister.

His biggest impact may have been wedding evangelical Christianity to the Republican party, to an extent once unimaginable.

“The culture wars being waged today by just about all the national Republican candidates — that is partly a product of Robertson,” said veteran political analyst Larry Sabato, director of the University of Virginia Center for Politics.

Robertson died Thursday at the age of 93.

Robertson's reach exploded with the rise of cable in the late 1970s. He galvanized many viewers into a political force when he unsuccessfully ran for president in 1988.

The next year, he created the deeply influential Christian Coalition. He sought to “influence and impact the trajectory of the Republican Party and turn it into a pro-life, pro-family party,” said Ralph Reed, who ran the coalition in the 1990s and now chairs the Faith & Freedom Coalition.

The Christian Coalition helped fuel the “Republican Revolution” of 1994, which saw the GOP take control of the U.S. House and Senate following the 1992 election of President Bill Clinton.

The son of a U.S. senator and a Yale Law School graduate, Robertson made political pronouncements that appalled many, particularly in his later years, placing the ultimate blame for the 9/11 attacks on various liberal movements. He claimed to have participated in prayer to keep a hurricane away from his Virginia base.

“Even Pentecostals, and I’ve known a lot, they’re not usually going to go that far,” said Grant Wacker, professor emeritus of Christian history at Duke Divinity School.

When he ran for president, Robertson pioneered the now-common strategy of courting Iowa’s network of evangelical Christian churches. He finished in second place in the Iowa caucuses, ahead of Vice President George H.W. Bush.

Robertson later endorsed Bush, who won the presidency. Pursuit of Iowa’s evangelicals is now a ritual for Republican hopefuls, including those seeking the White House in 2024.

Reed pointed to former Vice President Mike Pence and Sen. Tim Scott as examples of high-ranking Republicans who are evangelical Christians.

“It’s easy to forget when you’re living it every day, but there wouldn’t have been a single, explicit evangelical at any of those levels 40 years ago in the Republican Party,” Reed said.

Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network started airing in 1961 after he bought a bankrupt UHF television station in Portsmouth, Virginia. His long-running show “The 700 Club” began production in 1966.

Robertson coupled evangelism with popular reruns of family-friendly television, which was effective in drawing in viewers so he could promote “The 700 Club,” a news and talk show that also featured regular people talking about finding Jesus Christ.

He didn't rely solely on fundraising like other televangelists. Robertson broadcast popular secular shows and ran commercials, said David John Marley, author of the 2007 book “Pat Robertson: An American Life.”

“He was the one who made televangelism a real business,” Marley said.

Robertson had a soft-spoken style, talking to the camera as if he was a pastor speaking one-on-one and not a preacher behind a pulpit.

When viewers began watching cable television in the late 1970s, “there were only 10 channels and one of them was Pat,” Reed said.

His appeal was similar to that of evangelist Billy Graham, who died in 2018 after a career with a towering impact on American religion and politics, said Wacker, of Duke Divinity School.

“He really showed a lot of pastors and other Christians across this country how impactful media can be — to reach beyond the four walls of their churches,” said Troy A. Miller, president and CEO of the National Religious Broadcasters.

When he ran for president in 1988, Robertson's masterstroke was insisting that 3 million followers sign petitions before he would decide to run, Robertson biographer Jeffrey K. Hadden told The AP. The tactic gave Robertson an army.

″He asked people to pledge that they’d work for him, pray for him and give him money,” Hadden told the AP in 1988.

When he was working on the book as a graduate student in George Washington University in the late 1990s, Marley got unfettered access to Robertson’s presidential campaign archives and saw a campaign plagued by internal strife.

“But, he put a lot of effort into his presidential campaign,” Marley said, adding that Robertson worked for at least two years to lay the groundwork for his presidential run.

Robertson relished his role as a “kingmaker” and liaison of sorts between top Republican leaders such as Ronald Reagan and evangelical Christians.

“That ended with George W. Bush, who was able to have that conversation on his own,” Marley said.

During his 1998 interview with Robertson, Marley said he saw the preacher as someone who was as comfortable with his failings as he was with his accomplishments.

“I saw someone who absolutely at peace with himself,” Marley said.

.png?w=600)