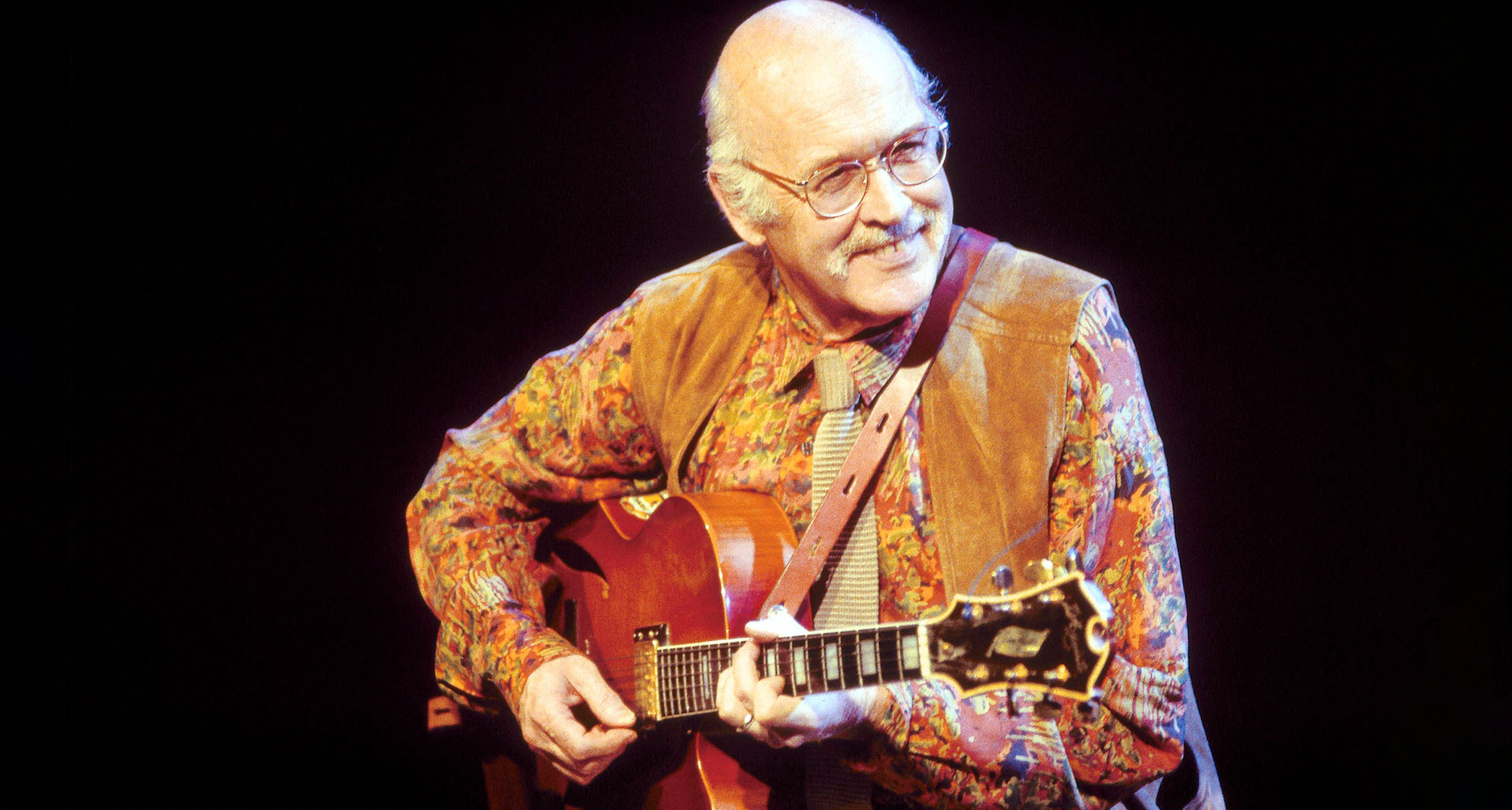

James Stanley Hall was born in New York in 1930 and first picked up the guitar aged 10. He began performing professionally in his teens and studied music theory and piano at the Cleveland Institute of Music.

Initially influenced by Benny Goodman’s guitarist, Charlie Christian, young Hall also had a huge interest in assimilating the dark legato sound of saxophonists such as Coleman Hawkins and Lester Young, along with spending a period studying classical guitar in Los Angeles with Vincente Gomez.

His unique approach to guitar, with exquisite taste, touch and sophistication soon brought him to the attention of the jazz community and his career began to gather momentum.

Hall’s first big break was landing the gig with drummer Chico Hamilton. This led to the release of his debut solo album in 1957, entitled simply Jazz Guitar. Touring and recording dates were to follow with legendary figures such as Ella Fitzgerald, Ben Webster, Bill Evans, Sonny Rollins and a host of others, with Jim balancing these engagements with his work as a bandleader and solo artist.

Hall’s career continued from strength to strength, but arguably he achieved even greater legendary status later in his life due to his collaborations with a younger generation of players, all of whom were quick to express their admiration for Hall’s ground-breaking style and unique approach to playing, with luminaries such as Pat Metheny, Mike Stern, Bill Frisell and John Scofield, right up to Julian Lage, Lage Lund and Kurt Rosenwinkel, singing his praises. Metheny even called Hall “the father of modern jazz guitar”.

Jim’s harmonic awareness, rhythmic placement and dynamic sensitivity are what sets him apart. His playing on the Sonny Rollins album The Bridge was particularly significant, as this was one of the first examples where the guitar legitimately replaced the piano as the principal harmonic instrument in the traditional jazz rhythm section.

Legendary jazz trumpeter Art Farmer perhaps said it best when he proclaimed, “When you have a guitarist of the calibre of Jim Hall, you really don’t need a piano. There are only a few piano players around who would be able to play with Jim, without being superficial.”

The musical examples that accompany this article explore a range of Hall-inspired lines, concepts and approaches, beginning with a transcribed II-V-I melodic line in C major. In our second example, we shine a light on five specific arrangement and orchestration concepts, moving through single-note lines, question and answer self accompaniment, double-stops, oblique motion and block chords.

Example three establishes effective drop-2 four-note voice leading on the highest strings, and we round things off with a contextualised musical example that puts our five Hall arrangement devices to work against a jazz-blues in C major with an extended tag section.

Lots to learn here so let’s get stuck in!

Technique focus: Think like an arranger

Jim Hall studied composition and arrangement and this training was evident in the parts he created. Many guitarists restrict their choices to single notes or chords. While this binary position can be musically effective, and is perhaps indicative of the old notion of ‘rhythm’ or ‘lead’ guitar, you can create some beautifully nuanced ideas if you blend or blur these roles.

Explore picking with a plectrum, fingerstyle, brushing with the thumb, hybrid picking and anything else available until you find an approach that resonates with you

While many of the defining voices in jazz relied upon single notes exclusively, such as Charlie Parker’s alto sax or the trumpet of Miles Davis, you could equally take inspiration from the multi-malleted vibraphone sounds of Gary Burton, or the exquisitely layered orchestrations of Bill Evans. Consider mixing one, two, three and all the way up to six notes at any one time to create a variety of musical effects.

Naturally, you’ll need to consider your technical options here, so explore picking with a plectrum, fingerstyle, brushing with the thumb, hybrid picking and anything else available until you find an approach that resonates with you and fits in with your style and with your technique preferences.

Example 1. Jim Hall II-V-I line

We begin with a transcribed Jim Hall line that neatly defines a II-V-I (Dm7-G7-Cmaj7) in C, followed by a I-IV-II-V-I, again in C (Cmaj7-A7-Dm7-G7-Cmaj7). It’s important to make the connection between the notes and the underlying harmony.

Also, as this sequences is so ubiquitous, you need to accumulate as much vocabulary in terms of lines, concepts and approaches as you possibly can, in all 12 keys and in as many locations on the guitar as possible.

Example 2. Five Hall approaches

To further this pursuit for extended vocabulary, here we outline five Hall-endorsed concepts and approaches, again situated against an extremely common progression in jazz, moving diatonically in 4ths, again in C and its relative minor, A minor.

Here we outline major and minor II-V-I sequences moving through single notes (2a), question and answer (2b), double-stops (2c), and ending with oblique motion ideas and block chords (2d and 2e).

Example 3. Drop 2 voicing connections

To play with as much harmonic security and inventiveness as Jim, you really need to know your chords.

Here we’re moving through each permutation of four-note ‘drop 2’ voicings, where the notes are rearranged so that the second from highest voice from a 7th chord (R-3-5-7) is transposed down by an octave (5-R-3-7), to give us a wider spread of notes and a more practical fingering for each inversion. It’s the same sequence as Ex2, but moving at twice the speed.

Example 4. Full piece

We end with a full piece against a C jazz-blues, putting the five ideas from Ex2 to work. Each four-bar phrase utilises each concept in turn as we articulate both the form and the harmony. Jim might exploit each idea more fully when time and space are less critical, so do this with your own explorations.

Begin by learning the example as written and then go through the five different approaches to create an entire chorus with each in turn.