In her hybrid critical memoir, Reading Lolita in Tehran, Azar Nafisi poses a knotty question regarding the spell of problematic books such as Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita.

A novel of shockingly egregious thoughts and actions, in which a 12-year-old girl is sexually abused and exploited in other ways, Lolita nevertheless offered a compelling text for Nafisi and her female students, all victims of the oppressive Iranian regime in the 1980s.

Nafisi had resigned from her university teaching position, and she and her students were continuing informal literary studies in secret in her apartment. “Are you bewildered?” she asks us. “Why Lolita? Why Lolita in Tehran?”

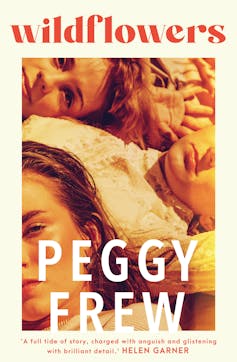

Review: Wildflowers – Peggy Frew (Allen & Unwin)

Despite its subject matter, Lolita continued not just to fascinate the class, but to provide solace and more. Why, asked one of Nafisi’s students, are readers filled with joy upon reading such novels? Does that mean there is something wrong with the novels, or with the readers themselves?

After some thought, Nafisi formulates an answer that satisfies both her and her students. First she reminds us every great novel is a form of fairy tale, and while fairy tales typically portray violence against children, they are also full of good, powerful magic – plus, they offer freedoms denied by reality, and an affirmation of life that counters real life’s transience.

When the author takes control of reality by retelling it, a new world is created. Thus “every great work of art […] is a celebration against the betrayals, horrors and infidelities of life”.

Read more: Trauma, resilience, sex and art: your guide to the 2020 Miles Franklin shortlist

Three sisters, estranged

This could be a stretch, and certainly defenders of novels like Lolita, post #MeToo, have their work cut out for them. But it worked for Nafisi and her students, as it has for me over the years – and Peggy Frew’s fourth novel, Wildflowers, reminded me of these comments once more.

The novel concerns three adult sisters, Meg, Nina and Amber. Once close, now estranged, they’re all set on differing paths – yet also united by the addiction of Amber, the youngest, and by her neediness, her vulnerability, her mistakes and the prospect of her salvation. That’s the initial premise, but it soon becomes apparent that vulnerability and need manifest in many ways, and by the end it is clear all three are victims, trying for different reasons to make good their failures and weaknesses.

The novel, however, is Nina’s. The opening section offers an intriguing depiction of someone gripped by dysfunction. In her late thirties, Nina lives alone and is refusing to take phone calls, to read messages or other mail, and to have contact with almost everyone.

She has ended all her affairs with men (of which more will be revealed). And she’s divesting herself of her belongings, limiting what she eats, and – strangest of all – wearing uncomfortable underwear, as well as shabby outerwear picked up from the streets, as a form of punishment. Meanwhile, she attends her menial job, which involves little interaction with anyone, and spends her spare time lying on the couch watching the vacant block opposite, where among dumped objects, wildflowers appear.

Or they may be weeds: Nina’s perspective is decidedly unstable. This scenario is precise, vivid and compelling. By the end of the first section, some 30 pages, more detail has been added. When Nina is finally pinned down by Meg, who is trying clumsily to repair a “mistake” made five years ago in relation to Amber, the many questions raised continue to compel us – but the next section then flips back in time. These questions are not going to be answered quickly or easily.

Read more: Touching, ferocious and poetic, the Miles Franklin shortlist is worthy of your attention

Lies, secrets and rescue gone wrong

One of the many impressive things about this novel is Frew’s great control of structure. While it is always Nina’s book, it is not always her story, and the experiences of Meg and Amber are cleverly nested within her point of view. They are given enough oxygen to prevent any suggestion of suffocating within Nina’s sometimes limited view of things, such as her view of the past.

It turns out this past contains a trauma that may be key to Amber’s behaviour and all that has followed — the well-meant yet ineffective coddling of her, as well as the family’s blindness to the true extent of her suffering and addiction.

Amber has been the golden child, the performer, the charmer, who seemed to have her future laid out in glittering success, while the lives of Meg — dependable and unimaginative — and Nina — cautious and cynical — have been bathed in shadow rather than sunlight. Nevertheless, their love for the vivacious Amber endures. As adults, they are prepared to take on the task of rescuing her.

The nature of this rescue — initiated by Meg, who determines that with their father dead and their mother incapable, enough is enough — turns upon lies and secrets. She and Nina trick their sister into going away on a holiday to north Queensland, where they intend to dry her out. Obviously things will not go to plan, and the subsequent conflict, suffering and sheer abjection presented makes this section of the novel horrifying and compelling.

Read more: Does a sibling’s gender influence our own personality? A major new study answers an age-old question

Atonement

As the fuller story of this family is revealed, so are the more recent details of Nina’s own failures and humiliations – in particular, her inability to form stable, loving relationships. Finally, those questions raised in the opening section are answered. Just as Amber is stripped down to be “cured”, so Nina needs to literally reduce her life as a way of finding the kernel of who she might be, as well as to atone for her complicity in that cure.

Frew’s dissection of family dynamics, with all its misunderstandings and failures, and her sense of the precarious line between loving care and harmful neglect, impart a threat of tragedy throughout the novel, which maintains our attention. Wildflowers is a painful, confronting and totally riveting novel, but Frew’s control of the story – evident on every page – promises not to engulf the reader in the sorrow it must expose.

The explanation that Nafisi offers as to why we cherish stories of abuse and misery concludes: “The perfection and beauty of form rebels against the ugliness and shabbiness of the subject matter.”

Frew’s great skill at the structural and other formal requirements of the novel, and her firm hold of the fictional reality she has created, are counterweights to the distressing subject matter. This makes reading Wildflowers an ultimately uplifting, rather than depressing, experience.

Debra Adelaide does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.