Earlier this year, the NHS announced that it had cut opioid prescriptions by almost half a million in four years. But opioids aren’t just available on prescription in the UK. They can be bought over the counter at pharmacies in the form of co-codamol – pills that contain codeine and paracetamol.

Each co-codamol pill contains a fixed amount of 500mg of paracetamol and between 8mg and 12.8mg of codeine, depending on the product. (Co-codamol with more than 12.8mg of codeine is only available on prescription.)

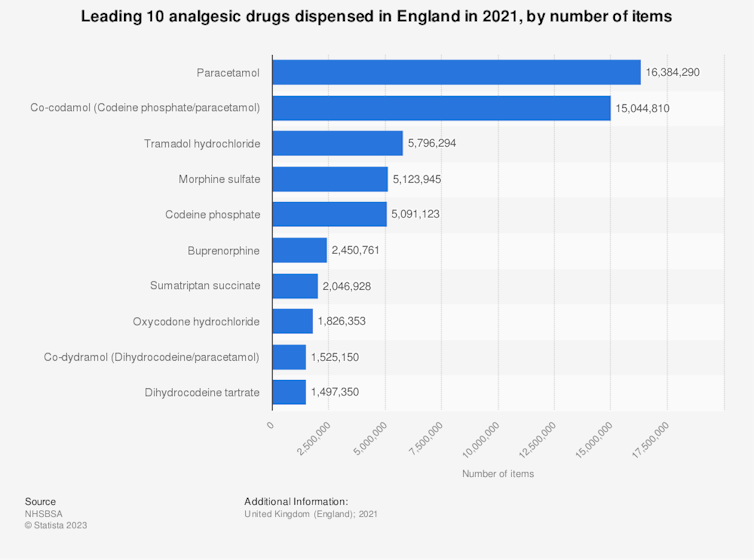

Co-codamol is the second most dispensed painkiller in England after paracetamol – with over 15 million packs sold in 2021. In 2023, the UK was estimated to be the third largest consumer of codeine at over 28 tonnes after India and Italy (75 tonnes and 33.5 tonnes, respectively).

Codeine is considered a “weak opioid” – 10mg of codeine is equal to 1mg of oral morphine. Once ingested, a liver enzyme called CYP2D6 converts codeine into morphine. However, some ethnic groups, such as people from north Africa, produce more of the CYP2D6 enzyme (so-called ultra-rapid metabolisers) and so are at greater risk of harm, even at regular doses.

Co-codamol is meant to be used to treat mild to moderate pain – such as period pain or toothache – but because it can also create a euphoric effect, it is at risk of being abused.

Codeine can cause serious harm, including dizziness, confusion, difficulty breathing and even death. These risks are especially great among ultra-rapid metabolisers, and among people who use other medications, such as benzodiazepines.

Some people buy co-codamol to treat their craving for heroin when there are local heroin shortages. But anecdotal reports suggest that this drug may be abused by people who start taking the pills to treat pain and end up being addicted.

Cold-water extraction

In theory, the paracetamol in the pills should prevent people from abusing them.

A maximum single dose of paracetamol for an adult should not exceed 1,000mg (two co-codamol pills) as it can harm the liver. However, online groups share a simple method called “cold water extraction” for removing the paracetamol.

Clinical toxicologists at Guys’ and St Thomas’ Hospital in London found case studies which suggest that the method is fairly effective at removing paracetamol from the pills, and a laboratory test backs this up.

It is not clear how widespread this form of tampering is, but a YouTube clip (now removed) showing viewers how to perform the procedure had been watched more than half a million times.

Pharmaceutical firms have yet to come up with an adequate way to prevent this kind of tampering.

Twenty-five countries have banned over-the-counter codeine

Given the pills’ potential for abuse, at least 25 countries, including Germany, Japan and the US have banned over-the-counter codeine sales.

Australia also implemented a ban in February 2018, despite warnings that people would switch to stronger opioids. However, researchers at the University of Sydney found that a year after the ban was implemented, there was a 51% drop in codeine overdoses overall (including high-strength codeine). And there was a 79% drop in overdoses from low-strength codeine, the type now only available on prescription.

In the UK, the drugs regulator, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), intervened in 2009 to reduce harms from over-the-counter opioids, such as limiting pack sizes to 32 pills per pack and adding prominent warnings on packs to not take the pills for more than three days.

In 2019, the MHRA conducted a review and decided against making co-codamol a prescription-only product.

While codeine-related deaths in England and Wales are fairly low, they have increased from 24 deaths in 1993 to 200 deaths in 2021 (200 deaths). It’s not clear if these deaths relate to over-the-counter codeine, prescription codeine or illicit codeine (say, bought on the “dark web”). Nevertheless, if codeine-related deaths continue to rise, the government may wish to reconsider its position on over-the-counter sales of codeine.

Amira Guirguis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.