Testifying before Congress, Chief Framon Weaver said his Alabama-based tribe, with roots dating back to the 1830s, held a distinction no one else wanted when it came to being recognized by the U.S. government, a stamp of approval that can mean millions in federal funding for Native American groups.

“It is clear that our tribe, the MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians, (is) the literal poster child for the structural failures evident in the federal recognition process,” Weaver told a committee.

That was in 2012, so long ago that Weaver is no longer chief. The MOWAs are still seeking federal recognition, and they're one of two state-recognized tribes hoping Congress will right what they see as wrongs of the past with the help of two influential U.S. senators who are retiring. It's an issue entwined not just with history but with the possibility of gambling revenues.

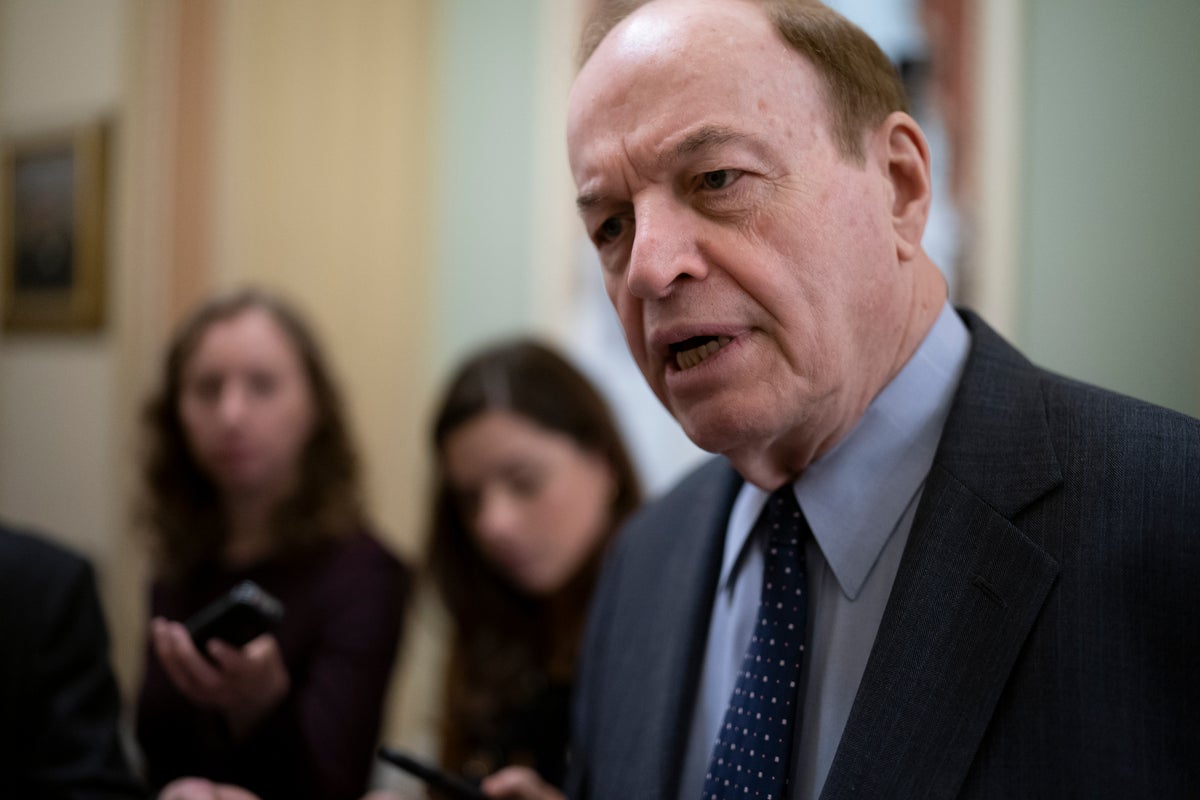

Alabama Sen. Richard Shelby, the senior Republican on the Appropriations Committee, is sponsoring legislation that would provide federal recognition to the roughly 6,500-member MOWA Band. GOP Sen. Richard Burr is handling similar legislation for the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, which with 60,000 members calls itself the nation's largest tribe not recognized by the federal government.

Both groups contend the process for gaining federal recognition has become adulterated and now favors money over history. They say that's partly because of the billions generated by Indian gambling, something they can't offer because of the lack of federal acknowledgement.

Similar recognition bills have failed repeatedly in the past, and it's unclear whether either one will win approval this year. But the current chief of the MOWA Band, Lebaron Byrd, has taken over Weaver's lobbying effort and hopes a final use of Shelby's pull will mean the difference this time.

“We always are optimists,” he said. “We don’t give up hope.”

Neither Shelby's nor Burr's offices responded to messages seeking updates on the legislation.

Byrd said obtaining federal recognition would mean between $50 million and $100 million initially in benefits including health care, education and economic development for the MOWA, who take their name from the band's location along the Mobile-Washington county line of southwest Alabama about 30 miles (48 kilometers) north of Mobile.

Passage of the Lumbee bill would cost about $363 million in expected spending from 2024-2027, according to an assessment by the Congressional Budget Office. The largest share, roughly $247 million, would come from benefits offered by the Indian Health Service, it said.

Both bills are opposed by a coalition of tribes already acknowledged by the U.S. government. A branch of the Bureau of Indian Affairs determines whether groups qualify as tribes through anthropological, genealogical and historical studies.

Groups that lose recognition bids before the agency can challenge those decisions through administrative appeals or lawsuits, something the MOWA have tried and failed. The Lumbee gained partial federal recognition through a bill in 1956 but are still blocked from key federal programs, a decision they continue fighting more than six decades later.

Politics shouldn't be allowed to short-circuit the process that other tribes have used to gain federal recognition, Native American groups opposed to the bills argued during a forum held at the U.S. Capitol in July.

“It is egregious when you can buy your way in,” said Margo Gray, chairwoman of the United Indian Nations of Oklahoma.

Congressional action would encroach on the rights of other tribes by cheapening the process, said Richard French, chairman of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

“When you claim to be someone that you’re not, you’re messing with the other peoples’ sovereignty,” he said.

Both the MOWA Band and the Lumbee Tribe contend history is on their side, even if other tribes aren't.

First recognized by Alabama in 1979, the MOWA Band says it is descended from Choctaws who remained in the area after Native Americans were forced to move west in the 1830s to make way for white settlers.

Purposely keeping a low profile and with only sparse written records to avoid detection after other groups were forced out, the MOWA Band was typically overlooked during the decades when Alabama was segregated by race. Members lived in the same rural community near the Mississippi line where many remain, said Byrd, the current chief.

The MOWAs sought federal recognition but were refused by the government in 1997 after a study determined the group wasn't part of historical Choctaw groups, and that only 1% of its members had documented Indian heritage. Subsequent appeals and a lawsuit failed, leading to the push for congressional action on acknowledgement.

First recognized by the state of North Carolina in 1885, the Lumbee have been seeking federal acknowledgement since 1888. Describing themselves as survivors of tribal nations from the Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Siouan language families, they live mainly in four counties in the southern part of the state.

Lumbee member Arlinda Locklear, an attorney who specializes in tribal law in Washington, D.C., said the passage in 1988 of federal legislation that allowed gambling operations by federally recognized tribes made it more difficult for new groups to gain recognition. Existing tribes didn't want to risk divvying up markets and gaming revenues with upstarts, she said.

“That’s what’s given the opposition wings in terms of the Lumbee,” Locklear said.

While the Indian Gaming Association said revenues nationwide exceeded $39 billion last year, the Lumbee have denied that gambling is their prime reason for seeking recognition. Instead, the tribes describe gaming as “the least of all motives” for its decadeslong pursuit.

The Alabama tribe nearly a decade ago opened a video gaming operation in a small building that's still located near the tribal office, but it was quickly shut down by authorities because the group lacked federal recognition.

Federal recognition could finally open the door to gaming operations, but the MOWA would be in competition with Alabama's only federally recognized tribe, the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, which already operates casinos. One way or the other, Byrd said, recognition could improve life for descendants of a group of people who refused to leave their homes nearly 200 years ago.

“One of our cemeteries dates back to 1800,” Byrd said. “We tell everybody we are the stayers.”