Ever since George Méliès first took us beyond Earth in 1902’s "A Trip to the Moon", filmmakers have been fascinated with cinematic depictions of living beyond the confines of our home planet. As the last few years have signaled a renewed interest in settling other planets such as Mars, it’s only natural for the dreamers among us to look to these interpretations for clues as to the particulars of this possible future. How will we travel to these destinations? How will we live? Who will pay for all of this?

Science fiction cinema offers answers speculative answers to all of these questions but can any of it provide any actual insight of worth? We spoke to Christopher Wanjek, author of "Spacefarers: How Humans Will Settle the Moon, Mars, and Beyond" (and occasional Space.com contributor) to find out just how feasible some of the more far-out cinematic takes on space settling might be.

The journey

One common trope of space settling films is the generations-long journey to an alternative 'Earth', (ten of which such planets we've previously listed here.) However, before settlement can even take place, the incredibly long journey is fraught with problems, including the deteriorating mental health of the travelers. Neil Burger's 2021 film, "Voyagers" dramatized this problem by positing a scenario where settlers traveling for the entirety of their lives were unknowingly treated with mood-altering substances.

Burger spoke to Space.com about his basis for the story back in 2021, but in reality no space agency is likely to be secretly dosing their astronauts any time soon. Wanjek agrees, for a key reason: "I don't think any space agency would attempt it for the practical reason that the crew needs to be hyper-vigilant to danger. Even a mood enhancer could potentially lead to an underestimate of potential danger during the mission."

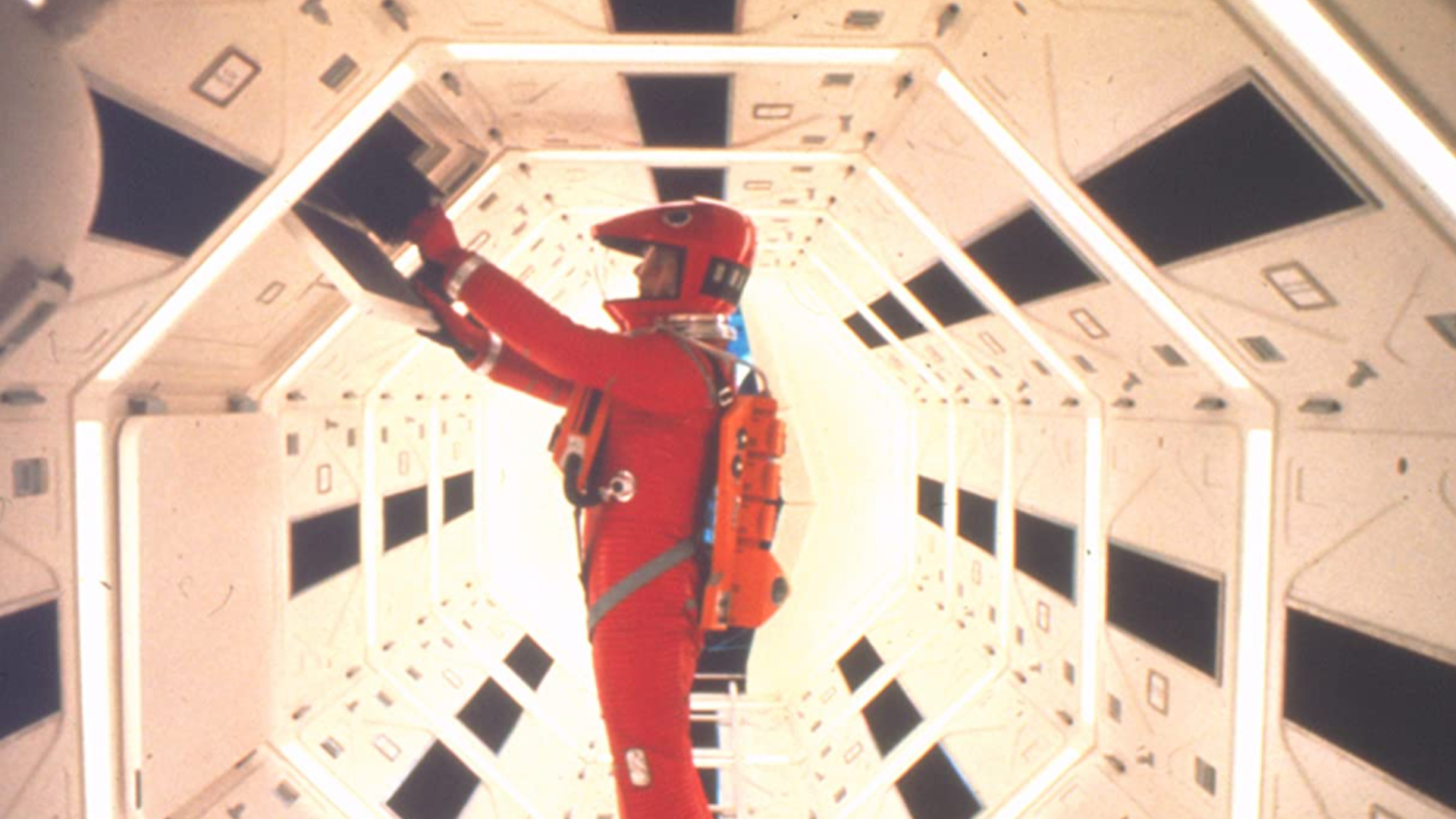

Instead, Wanjek argues that positive mood-altering will be focused on through "craft and habitat design, lighting, communications, entertainment, and food." He adds that "we don't want the travelers to succumb to depression. Habitat design includes using colors and shapes that provide a sense of openness despite the limited space. Lighting that promotes both wakefulness and sleep. Good food remains a standard depression-fighter, as I mentioned in 'Spacefarers'. I don't doubt that herbal teas or quite possibly an anti-depressant drug could accompany astronauts on long journeys. But their intent would not be sinister, as seen in 'Voyagers'."

There’s a wider aspect to craft design that other sci-fi movies such as 2015's "The Martian" have considered though, especially for longer-term habitation and that's artificial gravity, something Wanjek believes is a must unless the journey can be significantly quickened:

"I think a rotating craft — such as that depicted in the movie 'The Martian', or a simple one I described in 'Spacefarers' in which a craft is tethered to a counterweight a kilometer away — is essential for visiting Mars if the voyage lasts more than three months," he outlines. "Currently the trip would take 9 months. With nuclear propulsion, maybe just two months. If that fast, then artificial gravity is less of a concern. But after nine months in zero gravity, you may not be able to function well on Mars, and this could lead to dangerous situations."

The author adds that “if we start colonizing Mars, then I think this implies a technology to get folks there quickly, in a few months, so, a rotating craft is less important”, but either way, Wanjek points out that the basic premise of the epic colonization mission seen in 'Voyagers' is inherently flawed. “If we had the technology to launch a massive craft to a distant star system to save humanity, we'd have the technology to live in artificial biospheres on Earth or Mars or even in orbit around Earth to save humanity,” he points out.

Living and loving

What about once we arrive at our destination, be it a planet or space station? As far back as 1968, Stanley Kubrick’s "2001: A Space Odyssey" offered us a glimpse of an elegantly-rotating space station in a now-iconic movie moment and Wanjek believes the need for artificial gravity outlined above could see this concept ultimately materialize: “I think the orbiting, rotating structure seen in '2001: A Space Odyssey' is a natural evolution to simple space stations we see today,” he states. ‘The thrill of zero gravity wears off after a couple of days. Tourists will seek a hybrid of a zero-gravity fun zone in the center of a rotating space hotel but the comfort of artificial gravity on the outer edges. Such structures fit well within our technical ability.”

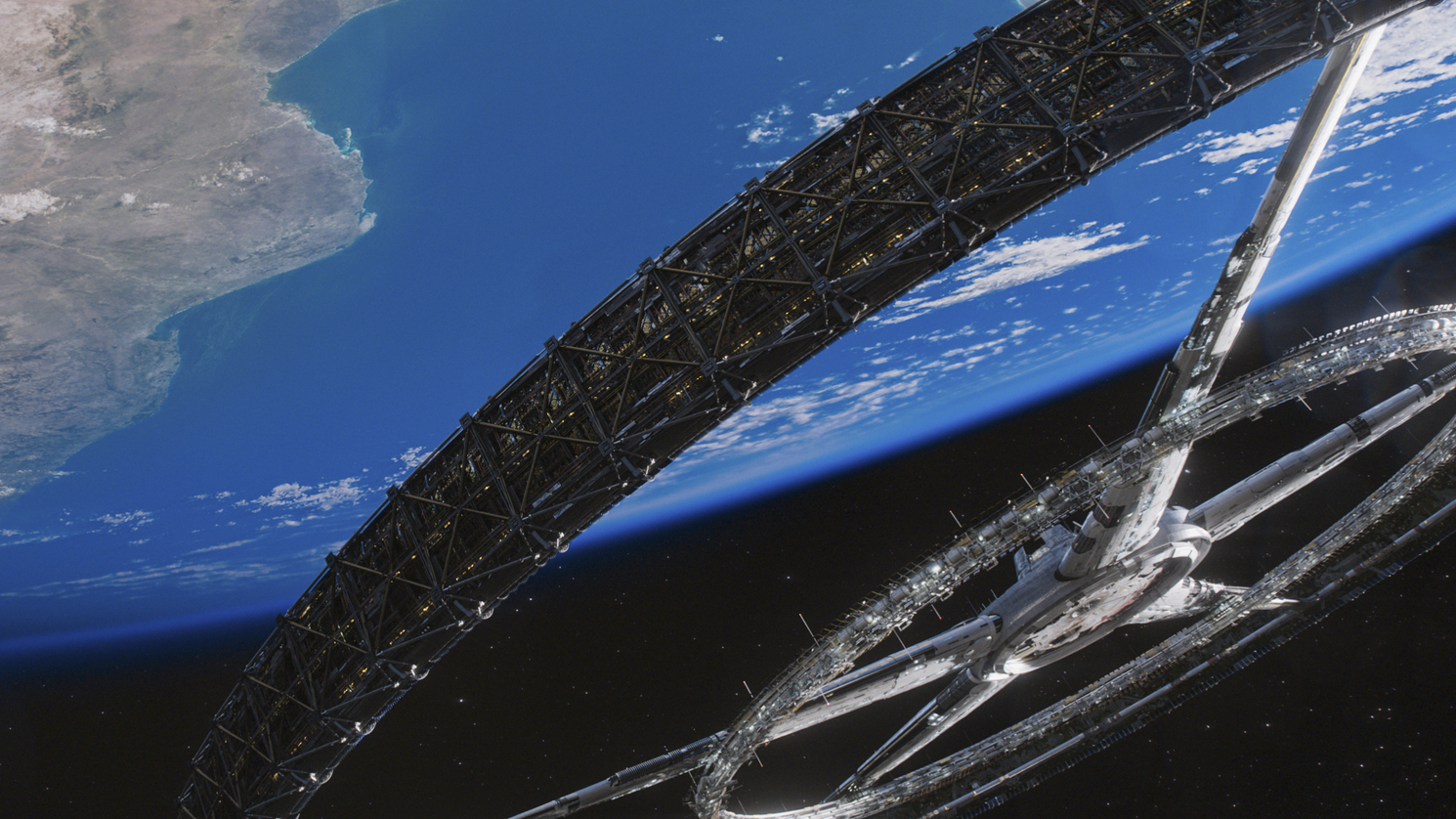

Whilst the title of Kubrick’s movie grandly suggested that the dawn of our current century would herald such progress, that has not proven to be the case, and Wanjek adds that until we have cheaper methods of moving materials into space (such as a space elevator), “launching materials into space is too expensive, so anything large and complex would cost billions of dollars/pounds to build. The investment,” he adds, “is too high.”

Of course, permanent living on such space stations would require procreation, with zero gravity sex being a fascination for several films, not least 2000’s "Supernova". Whilst it’s obvious to see the aesthetic potential for filmmakers, Wanjek wonders why it’s even an issue: “On generation ships, we'd have an artificial gravity. On the Moon… well, we will never colonize the Moon because there's no need or desire to. The focus should be on gestation and raising children. Women likely can conceive and birth a child in the 0.38G of Mars, but can a child develop properly and procreate as an adult on Mars? That's the million-dollar question. I don't know. No one knows. You'd need to test this on animals first.”

Footing the bill

So who’ll pay for this life beyond the stars? Science fiction cinema tends to go in one of two directions. Movies such as 1982’s "Blade Runner" or 1986’s "Aliens", perhaps wary of the growing influence of corporations during the 80s era of Reagonomics, sketch out a future where settlers are comprised of the lowest class humans or even synthetic beings, working for corporations whilst living in toxic and dangerous conditions. Alternatively, the 2013 film "Elysium" depicts an elite space station just beyond Earth’s orbit, populated and paid for by ultra-wealthy private citizens.

Whilst Wanjek sees corporate involvement as important to the settling of space, he dismisses the notion of space settlements being only for the upper or lower echelons of society as little more than a dramatic construct, as well as pointing out that there needs to be a valid reason to establish a settlement in the first place. “Let's consider the Moon,’ he argues. “Let's imagine that helium-3 fusion is feasible. Seems to me that a company would set up operations on the Moon to mine the helium-3 there (because there's basically none on Earth). Much of the work would be robotic, but I can envision dozens or even hundreds of workers involved in various mining operations… again, if such mining were somehow profitable, which it isn't now. I think a smaller number of people could be employed in a lunar tourism industry. But I don't think this would be ‘colonization’ in that families wouldn't move there. I think the gravity is too low to raise children, and life there would be gray and claustrophobic.”

When it comes to Mars, Wanjek is even less sure that corporate-led settlement could happen because it’s as yet unclear as to what the red planet has that we might need. Instead, he argues that industry will be led “as a support of government activities”, although he does point out that the potential long-term habitation offered by Mars affords some potential: “It's a vibrant world with colorful skies, tall mountain peaks, and fascinating geographical features,” says Wanjek, “so, more infrastructure and corporate presence could be there. One could envision ‘company towns’ with a corporation transporting workers and their families to build Mars, as we built the ‘new world’ centuries ago.”

Such ‘frontier towns’ would be a far cry from the luxurious off-world living glimpsed in "Elysium", an idea that Wanjek considers to exist only in the realm of fiction. After all, he argues, ‘it seems to me that the wealthy could just take over a region on Earth.” That said, he does believe that “space will be for the ultra-wealthy for decades to come, much like air travel was... or an African safari was... or an Antarctica tour is. And I'm fine with that. I'm happy about it,” he says. “I'm happy to see billionaires launching themselves into orbit. They are pioneering the path for the rest of us.” Certainly they are blazing a path more than cinema, it would seem which scores pretty dismally in predicting living beyond the stars. Still, if nothing else these sci-fi movies fuel dreams and whilst that’s not the same as fueling rocket ships, they at least encourage us to keep looking beyond the confines of our home planet and imagining something more.

You can find a copy of Christopher Wanjek’s illuminating read, "Spacefarers: How Humans Will Settle the Moon, Mars, and Beyond" right here.