The impact of filmmaker Ousmane Sembène’s work should not be understated. His films, made in the neorealist style, were concerned with working-class people and tended to use non-professional actors. This allowed him to represent African life on its own terms, focusing on African characters as distinct, thinking and speaking individuals beyond predictable stereotypes. He was also the first to make a film in an African language. For this, he is considered the “father of African cinema”.

Famously stating “Europe is not my centre”, he was a leading voice among a group of filmmakers, often referred to as the “pioneers” of African cinema, who emerged in the 1950s and ’60s.

Sembène (1923-2007) was deeply motivated by a need for political and social change. He was equally a fierce critic of colonialism and its legacies, the post-independence realities across Africa, as well as the strictures of “tradition”. These themes feature heavily across his nine feature films made between 1966 and 2004.

As we celebrate his 100th year and rediscover his films, we can gain a better understanding of Sembène, and the themes of his work, by looking at the turns his life took that led him to cinema.

He was born in the trading port of Ziguinchor, in the Casamance region of colonial Senegal. His early life included working as a fisherman and a variety of manual jobs. He then enlisted as a serviceman in the French colonial army. Known as tirailleurs, he joined a sort of light infantry reserved for colonials in the French army.

Following service in the second world war, Sembène took on an activist role back in Senegal in the burgeoning labour movement. By the late 1940s, however, he was back in France, working on the docks in Marseille. Here, into the 1950s, his engagement with trade union activity and radical left-wing politics grew significantly. This activism would converge with a growing interest in literature and anti-colonial politics.

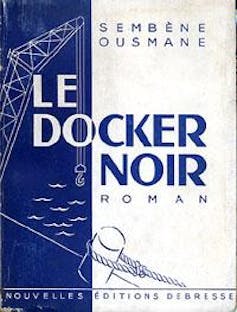

In France, Sembène was in the company of Black writers such as the African American Richard Wright, the Jamaican Claude McKay, and the Haitian Jacques Roumain. In this company, he would publish his first novels Le Docker Noir (The Black Docker, 1956) and Les Bouts de Bois de Dieu (God’s Bits of Wood, 1960).

Le Docker Noir draws on his experiences as a Marseille dock worker and Les Bouts de Bois de Dieu on his involvement with workers taking industrial action in the seven-month Dakar-Niger railway strike of 1947-48.

Sembène would write a total of six novels, four novellas and a collection of short stories. Many of these were adapted by him for the cinema, and are among his significant filmography over six decades.

As his official biographer Samba Gadjigo has said, Sembène “made films by any means necessary”. This takes on a specific significance within African societies emerging from colonialism from the 1950s onward.

Having achieved relative success with his writing, he was inspired to move towards the cinema by the possibility of reaching a wider audience, particularly those who did not speak French. Paired with his anti-colonial political commitment, Sembène among others of his generation prioritised the significance of having films made by Africans.

After a year at the Gorki Studios in Moscow, he returned to Senegal, emerging in 1963 with the original short film Borom Sarret. Among his most critically celebrated films are La Noire de … (Black Girl, 1966) and Mandabi (The Money Order, 1968), which have both recently been restored.

Pivotal works

For those who want to explore Sembène’s back catalogue, here are five acclaimed films as a brief introduction to his work. They reinforce him as arguably the most important African filmmaker of the 20th century.

1. La Noire de… (1966)

Colonialism takes on a new and traumatic dimension through the consequences of migration from Senegal to the Paris metropole. The film follows Diouana, a young Senegalese woman, as she moves to France with her colonial employer to continue working as a nanny. It focuses on the trauma of her exploitation and alienation in France – for Diouana, the reality is tragic. The script is based on a short story from Sembène’s 1962 collection, Voltaique.

2. Mandabi (1968)

Returning to the theme of migration and its paradoxes, this film follows an unemployed man in post-independence Senegal who receives a money order for a substantial sum from his nephew working as a street cleaner in Paris. In his attempts to cash the money, the man must battle Kafkaesque bureaucracy and unscrupulous urban dwellers who regard him as an opportunity for their own short-term survival. This was the first ever film made in an African language.

3. Xala (1975)

Probably Sembène’s most widely viewed film, Xala directly addresses the idiosyncrasies of post-independence states like Senegal and the impotence, both metaphorically and literally, of their elites. The film is centred around a successful businessman, El Hajj, who in celebration of his new status in the governing body of the newly independent state, decides to take a third wife. His inability to consummate the marriage with his much younger bride leads to spiralling humiliation as attempts are made to find a cure (or xala) for his impotence.

4. Camp de Thiaroye (1988)

The historical events that unfolded at a transit camp for African servicemen (tirailleurs) near Dakar, Senegal in 1944 are dramatised in this film. These soldiers had fought for France in the second world war but, on returning to Africa to await their demobilisation, are confronted with poor living conditions – their severance pay being first delayed and then drastically cut. This leads to a revolt against the French authorities which has bloody consequences. Here, Sembène offers a subtext of pan-African solidarity in response to fascist atrocities, colonial injustice, and universal violations of human rights.

5. Moolaadé (2004)

Women’s empowerment in the midst of controversial circumstances is a preoccupation in Sembène’s work, and his last film focuses on female circumcision. Moolaadé examines the complexities of both “tradition” and “modernity” in relation to gender roles and the politics of the practice. The film moves through the complex aspects of the prevailing debates across both gender and generational lines.

imruh.bakari@winchester.ac.uk is affiliated with University of Winchester and June Givanni PanAfrican Cinema Archive.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.