The world’s energy bill for 2022 is set to be the highest ever, topping US$10 trillion (£8.3 trillion). This is the total price paid for all forms of energy across all sectors by all people. Something like 80% of this bill is for coal, oil or gas, or for electricity generated from these fossil fuels.

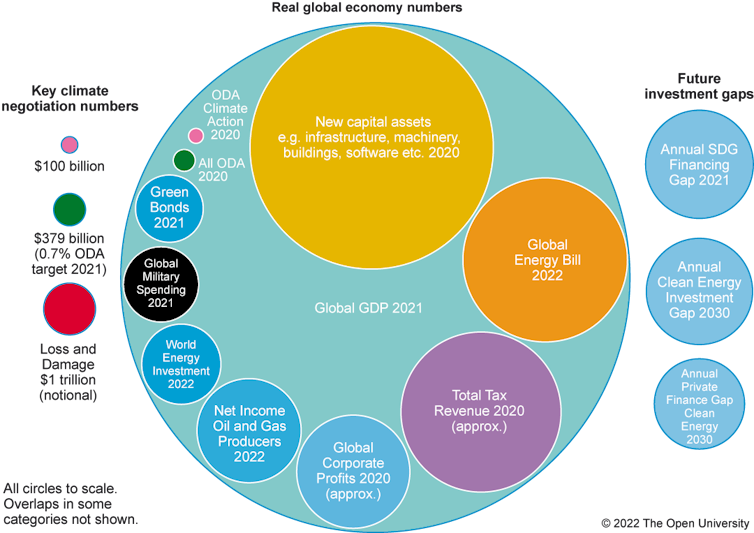

Our addiction to energy is equivalent to more than 10% of global GDP. Infuriatingly, a lot of the energy we buy goes up in smoke or wasted heat before it even gets a chance to do any useful heating, cooling, cooking, transporting or manufacturing. Energy spending is now greater than total global tax revenue or corporate profits and dwarfs military expenditure. When energy prices are high, as they are now, a good proportion of our overall energy bill becomes profit in the pockets of oil and gas producers.

In the natural world, most species thrive by exquisite optimisation of their energy consumption. Seemingly-lazy animals ensure they use just enough energy to survive – and no more.

Our high-energy, high-carbon human society is rather different. Each year, we spend no less than four times more on our energy bills than we do investing to minimise and avoid those bills in the future. The good news is that the tide has turned and annual investments in clean energy (US$1.4 trillion) are now greater than investments in fossil fuel systems (US$1 trillion).

But we still waste energy spectacularly, and we could quickly and practically do something about it. The IPCC has said that “there are options available now in every sector that can at least halve emissions by 2030.”

When energy is expensive and the climate clock is ticking, this is a massive missed opportunity to pump solar and wind energy instead of oil and gas.

COP in context

Numbers involved in the recent COP27 climate negotiations are put to shame by the amount being spent in the real world outside the negotiating rooms.

For instance, a goal to send US$100 billion a year to climate-vulnerable nations by 2020 was introduced in 2009 and enshrined in the 2015 Paris Agreement but has still not been met. The latest figure was US$83.3 billion in 2020.

US$100 billion is just 1% of global consumers’ energy bills. Even the US$1 trillion cost of climate-related loss and damage is still just 10% of our current annual energy bill.

It is still possible, even now, to stick to the Paris Agreement and limit global heating below 2℃ through a rapid transition towards clean energy systems. But it will require a lot of investment. By the end of the decade, the amount of extra funding and investment needed to achieve our climate and sustainable development goals will be double the amount the world invests in all kinds of energy this year.

Harnessing the rules of finance and economics

The global economy is of course dynamic. The IEA’s latest energy scenarios are based on a global economy in 2050 of more than double its current size and an increase in human population from 8 billion to just under 10 billion. With long-term historic growth at around 3% a year, things are always changing. This in turn means a lot of investment in infrastructure happens “naturally”. Indeed, each year, around a quarter of our GDP is spent on new machinery, buildings and infrastructure.

But, as part of a shift away from fossil fuels, we could reduce some of that investment in fossil fuel infrastructure, meaning fewer new oil wells, coal power plants, gas pipelines and so on. That money could instead be invested in clean energy systems.

There’s more: investments in energy efficiency and renewables can take into account the avoided future costs of energy along with the environmental and social problems associated with fossil fuels. We call this net incremental investment and cost accounting.

It may not sound sexy, but this way of thinking is possibly our greatest weapon in the fight to limit the costs of climate change. It is why capital investments in the real world are being redirected towards energy efficiency and modern clean energy systems.

While the second law of thermodynamics means we always have to work (often hard) to gather and concentrate energy into forms and products we need, we can do much better at exploiting the laws of finance and economics to tackle climate change. Reducing our global energy bill is the key.

Stephen Peake does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.