The UK is now approaching its third Christmas of the COVID pandemic. And this year feels different. There’s little question we’re in a better position compared with 2020 and 2021.

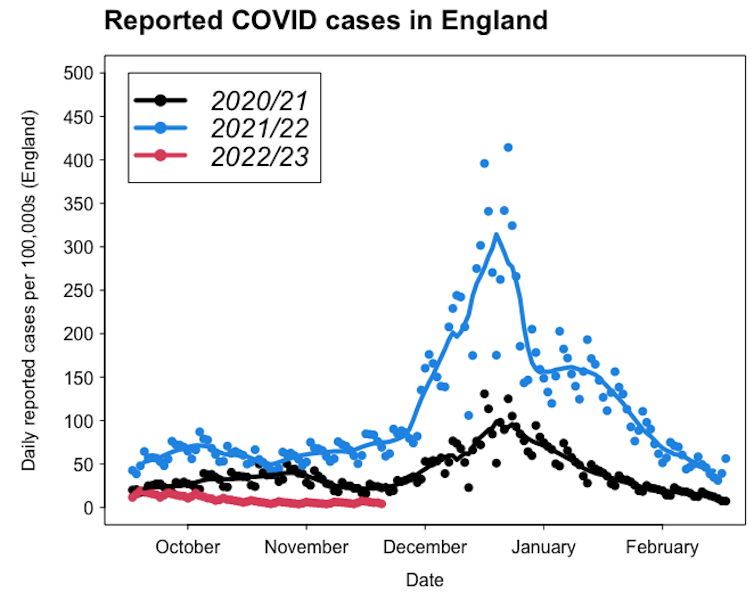

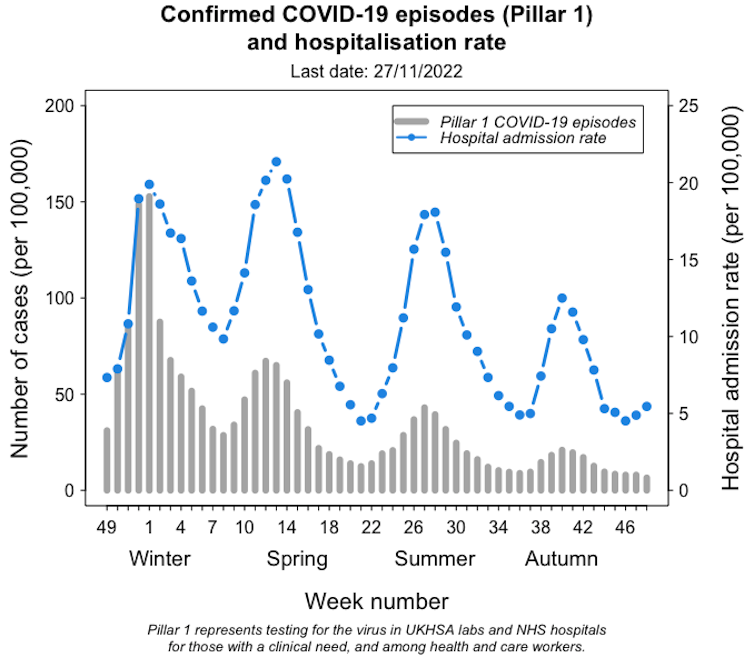

In 2020, Christmas plans were significantly curtailed, with a range of restrictions in place across the UK. But winter social mixing that took place before a full national lockdown was implemented in early January 2021 caused the number of deaths to rise quickly, reaching levels similar to those in the first wave.

At the same time a new variant, alpha, was starting to spread. On a brighter note, the first vaccine doses were beginning to be administered, offering hope for suppressing the pandemic.

One year later, in December 2021, predictions were more optimistic, with 70% of the UK population having received two vaccine doses. But the spread of the omicron variant threatened festive plans.

A huge wave of cases followed and quashed any notion that herd immunity may be achievable with this virus. But vaccinations were successful in keeping numbers of deaths relatively low.

COVID cases and deaths in England in 2020, 2021 and 2022 winter seasons

As we approach our third COVID Christmas, there’s talk that we’re now “post-pandemic”. But the virus is still very much with us.

So, how does the COVID outlook for this winter differ from the previous two? Let’s look at some key factors which will determine how things might play out.

Immunity

When we’re infected with SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), or when we are vaccinated, the immune system is primed to protect against future infections.

The relative levels and duration of immunity against SARS-CoV-2, either attained through infection (“natural”), vaccination (“artificial”), or both (“hybrid”), are not completely clear. But 66% of the world’s population is estimated to have some form of immunity against SARS-CoV-2. This immunity is more likely to provide protection against severe illness and death, but offers some protection against infection.

In countries such as the UK and the US, more than 95% of people currently have immunity (measured via antibodies), up from 5% in December 2020. There’s no doubt that the virus now has a lower chance of inflicting serious damage compared with two years ago.

Read more: COVID treatments and prevention are still improving – so the longer you can avoid it the better

At the same time, the experience of the winter 2021-2022 wave shows that vaccination alone is unlikely to eliminate the virus. In contrast to smallpox, rinderpest, and even measles, we might need to learn to live with it.

A steady influx of children born without exposure to COVID and waning immunity among adults is likely to fuel future waves.

A changing virus

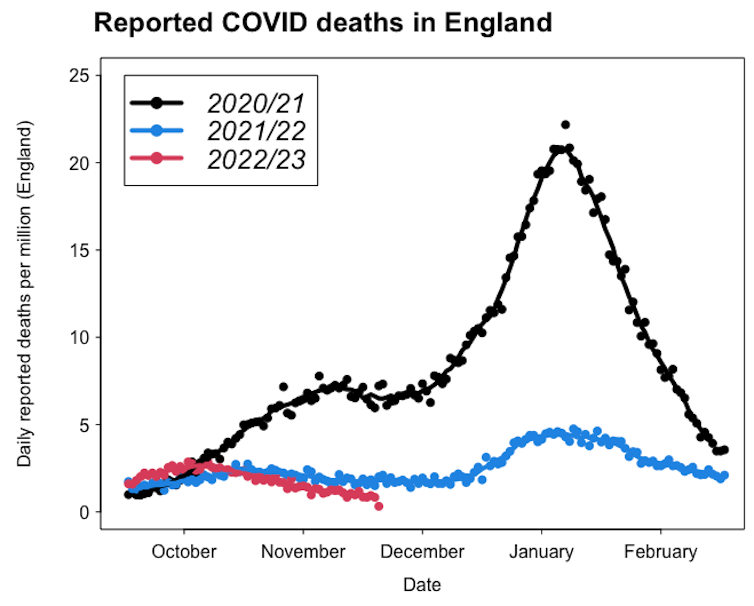

In 2020 there was speculation that in contrast to other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 would not mutate fast enough to cause problems after vaccination. This has proved wrong, and the rise of variants such as alpha, delta and, most recently, the subvariants of omicron, have shown their potential to escape immunity from vaccination and prior infection.

COVID variants (England)

Since mid-2022, the virus has been spreading not as a single dominant variant but more as a mixture of descendants. When transmission is high in winter, a new dangerous variant might emerge and cause a large wave like a year ago. But at the moment there’s no clear sign that this might be happening.

Transmission

To spread, SARS-CoV-2 must pass from an infected person to a susceptible one, travelling in tiny particles through the air. Like other respiratory diseases, COVID spreads more when people mix indoors, like in schools, offices, or at Christmas parties. Lockdowns, self-isolation and masks have been remarkably successful in slowing down the epidemic.

But the economic and social effects of lockdowns have been controversial. As the vaccines currently protect the majority of people from severe illness and death, there is little will for reintroducing the restrictions. But, the return to pre-pandemic contact levels is likely to keep COVID circulating for longer.

Ventilation, masks, and strengthening our immune systems are currently the best ways to counterbalance the effect of the increase in social contacts on COVID transmission.

Read more: COVID, flu, RSV – how this triple threat of respiratory viruses could collide this winter

New year, new wave?

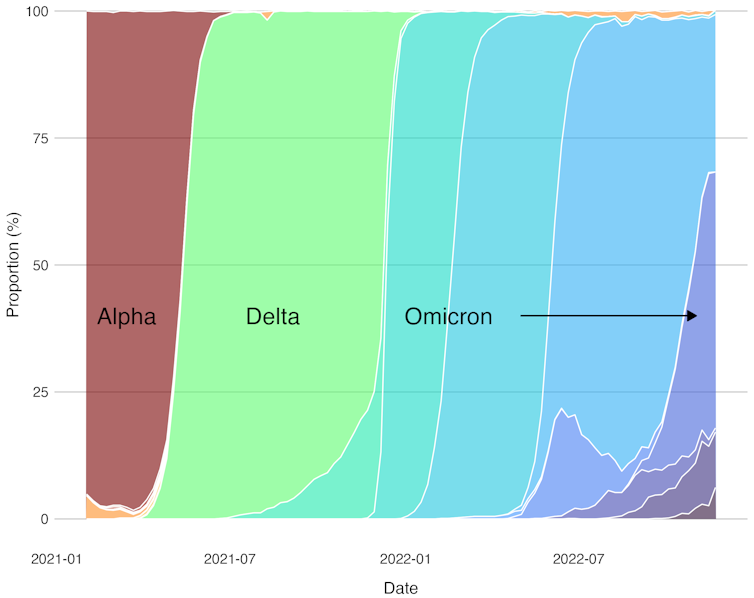

Predictions of a large COVID wave as we head into winter have so far not materialised. The most likely scenario is that the small-scale outbreaks will continue throughout winter as COVID becomes “endemic”. We might already be seeing the beginning of a new wave with COVID infections and hospitalisations rising in England since the beginning of December.

Weekly COVID cases and hospitalisations in England

China is currently the biggest unknown as the country moves away from its zero-COVID policy. It remains to be seen to what extent large wave of infections there might spill over to the rest of the world.

The impact of multiple infections could be the biggest problem the UK and similar countries face in the future. We now know each reinfection adds a risk of developing serious health complications and long COVID.

We may well be able to enjoy more freedoms this Christmas than we could the past two years. But individual people and societies will be feeling the effects of the COVID pandemic for many months, if not years, to come.

Adam Kleczkowski receives funding from the UKRI and the Scottish Government.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.