As state agencies front a Royal Commission, David Williams reviews the country’s history of treating mental illness with shocks, drugs and, long ago, lobotomies

It was a grisly, life-altering graduation.

After being subjected to years of “ineffectual” regular electroshocks, and experimental drug treatments aimed at inducing convulsions and coma, “chronic and intractable” patients were offered to neurosurgeons in Dunedin as potential candidates for pre-frontal lobotomies.

The results of 65 procedures, also known as leucotomies, performed between 1944 and 1950 were reported in a New Zealand Medical Journal article, written by surgeons D. Gilmour McLachlan and Murray A. Falconer.

The 1950 article describes: “In this procedure white matter of the [brain’s] front lobes on each side is severed blindly by a blunt instrument inserted through a laterally placed burr hole.”

It concluded: “Eighty per cent of the whole group were benefited and two patients died.”

Most patients came from publicly run mental hospitals, and were listed as suffering from long-standing psychotic conditions such as schizophrenia, manic depression and paraphrenia (paranoid delusions).

Eight came from Ashburn Hall, a private psychiatric hospital in Dunedin, whose superintendent, Reginald Medlicott, would go on to become foundational president of the Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.

Four patients had chronic pain.

Selection for leucotomies was “rigorous”. Patients must have spent at least four years of illness, other forms of treatment would produce no benefit.

Essential criterion for suitability for lobotomy was “chronic emotional tension in some form, whether it be extreme agitation, ‘mental pain’, or disorder of conduct”.

“In 11 cases a major indication for recommending lecuotomy was violent and uncontrolled behaviour, with in 3 cases there had been repeated suicidal attempts.”

Patients were prepared using electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT – electric shocks rendering the patients unconscious.

But behind all this “success” were complications, suggesting the study was downplaying the damage caused.

On average, patients spent more than six months in hospital after leucotomies.

Early on, they were confused and disoriented, mute, and showed “lethargy, apathy and inattentiveness”. They were incontinence and uncooperative. Women didn’t regain regular menstruation for four-to-five months.

Four men and three men developed epileptic fits. All but one were unlikely to leave hospital, the article said.

There was also a “loss of originality, creative ability, and the imagination upon which it is founded”, although these changes were noted as “slight”.

“Even on economic grounds, the results are encouraging,” the Medical Journal article said, as those who benefited would otherwise still be inmates of mental hospitals, “and so a charge on the state”.

Sixteen patients improved enough to return home, while 14 went back to work, as nurses, clerical workers, shop assistants, domestic servants, factory workers, and a freezing works’ foreman.

“These results in the psychotic cases are particularly gratifying as all were deemed incurable by all other means.”

Despite the gushing write-up, the barbaric procedures were stopped soon after, and by the 1970s were banned in many countries.

“They were places of abuse then and they continued to be right through to their closure in the 1990s.” – Mike Ferriss

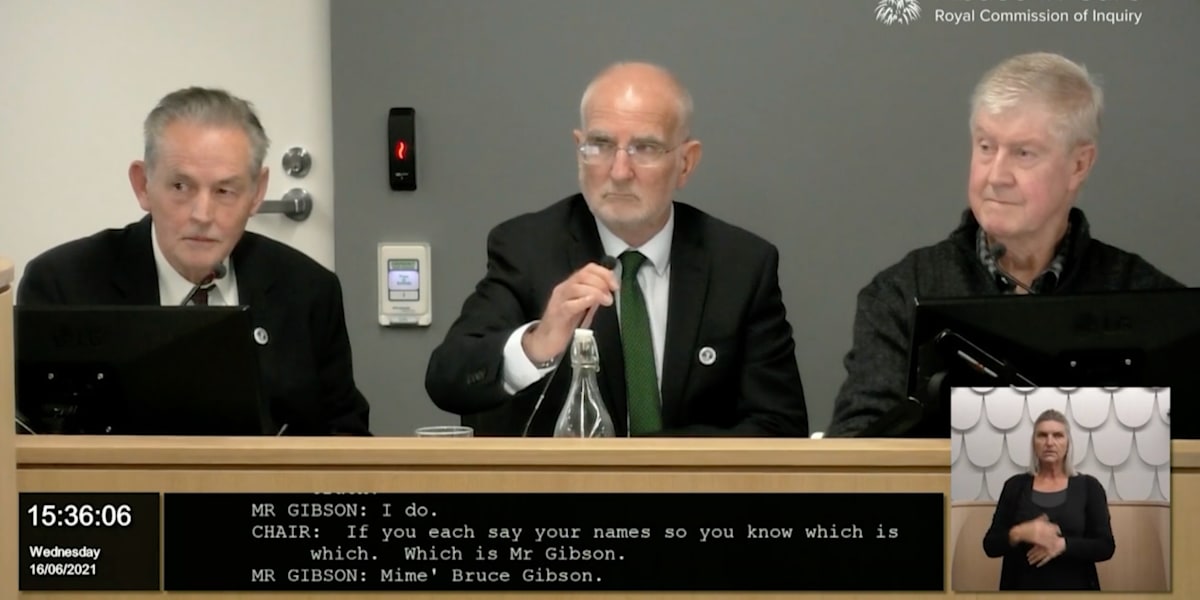

This dark, Dunedin episode is chronicled in a 100-page statement to the Abuse in Care Royal Commission by the Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR), a Church of Scientology-aligned watchdog group established in this country in 1975.

In the statement, Mike Ferriss, CCHR’s director, accuses the authors of the 1950 Medical Journal study of downplaying the damage done to lobotomised individuals.

Ferriss tells Newsroom: “New Zealand was far from a backwater in terms of experimental psychiatry, it was right up there with lobotomies and trying out new methods of electro-shock.”

A little-known booklet, published in 1946, called Misery Mansion, Grim Tales of New Zealand Asylums, detailed how people were held against their will, with little monitoring and few legal safeguards. Author Arthur Sainsbury said more people died in asylums each year than were discharged.

Ferriss agrees with Sainsbury, that asylums were dinosaurs of mental health care.

“They were places of abuse then and they continued to be right through to their closure in the 1990s.”

CCHR’s history of psychiatry and mental health treatment in this country relies on more than 20,000 documents, including private medical files released with the permission of former patients and their families.

The historical overview provides a useful primer for the Abuse in Care Royal Commission’s two-week hearing, starting today, in which state agencies will respond to the abuse and neglect of children, young people, and vulnerable adults.

(The commission’s terms of reference state detailed examinations must focus on abuse in care between 1950 and 1999.)

Those scheduled to give evidence include Police Commissioner Andrew Coster, Director-General of Health Diana Sarfati, and Chief Ombudsman Peter Boshier. On the hearing’s final day, August 26, Peter Hughes, the Public Services Commissioner, who spent 10 years heading the Ministry of Social Development, will appear.

Asked for comment, three government departments provided emailed statements to Newsroom.

MSD’s deputy chief executive of people and capability, Nadine Kilmister, says: “We fully support the Royal Commission. As this query relates to psychiatric care and administration of medications to patients, this query best sits with [the Ministry of] Health.”

This stance overlooks psychiatric treatment delivered in Department of Social Welfare institutions, such as Fareham House, in Featherston, Wairarapa, and Epuni Boys’ Home in Lower Hutt.

A 1975 paper researching psychiatric interventions in such institutions said were it not for children in Social Welfare care, most child psychiatric units in hospitals couldn’t have got off the ground.

At the notorious Lake Alice psychiatric hospital, which had a child and adolescent unit, youngsters, many of them state wards, were shuffled between departments, arriving there from social welfare homes or Department of Education-run schools.

There they were subjected to painful injections and electroshocks as punishment, actions a United Nations committee has deemed torture.

Ministry of Health’s chief legal advisor Phil Knipe says: “It would not be appropriate for the Ministry of Health to comment ahead of giving evidence at next week’s hearings.”

Oranga Tamariki’s deputy chief executive of quality practice and experiences, Nicolette Dickson, says: “This is an important issue for the Commission. It is appropriate that they hear evidence directly from Crown agencies and this will occur during the institutional response hearing.”

The CCHR report refers to a study published in the NZ Medical Journal in 1958 detailing the “treatment” of 25 women over eight years at Nelson’s Ngawhatu Hospital.

After the supposed failure of other treatments, intensive electroshocks were delivered – an electric form of lobotomy, effectively. They would take patients beyond “gross confusion” to “temporary dementia”, “with complete disintegration and loss of personality”.

“The patient may show gross regression until she curls up into the antenatal position,” said the paper, written by psychiatrist Rina Moore.

Eradicating a person’s personality was not treatment, CCHR said, but abuse and torture.

A former patient who received intense ECT during a five-month stay had to ask the nurse who spoon-fed her if she was married and had children.

The memory loss followed her when she was discharged – left broken, depressed, and fearful. She suffered frequent nightmares, severe insomnia, disorientation and hallucinations.

A trainee nurse who worked at Ngawhatu in the 1950s told CCHR in the 1990s she held down patients while they were shocked, 12 or more times each day. Afterwards, the patients, some of them with burns on their temples, were like “cabbages”.

They had to be fed and fully nursed. Some patients were confined to their beds and slept continuously.

A nurse aide who worked at Ngawhatu in about 1960 had to pin down her own sister.

Her sister’s medical records show a 10-day spell of treatment with an anti-psychotic drug, and, after a five-day gap, a 14-day period of ECT, during which she tried to escape.

By the end of this treatment, she was “mute, confused, incontinent and she required full nursing care”. She went back on anti-psychotics after suffering from hallucinations.

During a nine-month spell at home she was vague, and couldn’t remember things, began smoking heavily and had no self-esteem. She was re-admitted to Ngawhatu and, in 1965, went missing. Her body was found three years later on a property adjacent to the hospital.

Moore’s paper claimed success with 19 of the 25 patients. However, CCHR said it verified 10 survivors of the treatment “never recovered”, and suffered ongoing memory loss and developed other mentally and physically debilitating conditions.

CCHR says these experiments were similar to the CIA’s secret mind-control programme MK-Ultra.

It was the era of “deep sleep”, also known as prolonged narcosis, promoted by controversial British psychiatrist William Sargant, at St Thomas’ Hospital in London.

NZ Herald’s head of business Fran O’Sullivan wrote about the “zombie ward” at Cherry Farm, just north of Dunedin, while she was a 20-year-old trainee nurse in the 1970s.

This was “deep sleep”.

As a Sunday News article from 1990 said patients were kept in drug-induced comas for days and even weeks on end, combined with electric shocks. The idea was to effectively re-boot the brain and erase bad memories. But patients suffered long-term physical and psychological problems.

The experimental treatment was supposed to be a last-ditch treatment for unruly and troublesome patients, but evidence showed this wasn’t always true – some victims had little or no previous treatment. Few patients benefited.

CCHR’s research found seven hospitals – including Christchurch’s Sunnyside and Invercargill’s Kew Hospital – participated in deep sleep or sedation treatment.

In one year alone, 52 people underwent modified narcosis at Cherry Farm. Many were “informal” patients, and none signed consent forms.

An inquiry was launched, and made recommendations in 1991. The report authors recommended a wider investigation but the Health Department never followed up.

Despite numerous complaints, and roughly 30 compensatory payments, no medical staff faced disciplinary action.

In Australia, meanwhile, deep sleep was banned in 1983 after at least 24 people died in the 1960s and 1970s. Many more were left brain damaged and paralysed.

Newsroom asked the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists for comment last Friday but hadn’t received a response by publication deadline.

Its website carries position papers on several issues:

- “Deep sleep therapy has no place in the treatment of psychiatric illness. It has not been demonstrated to be an effective treatment for any psychiatric condition and has unacceptably high morbidity and mortality rates.”

- “Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a highly effective treatment with a strong evidence base, particularly for the treatment of severe depressive disorders.”

- “The RANZCP strongly condemns the use of torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatments or punishments in any context. The RANZCP is committed to the abolition of torture, and to providing effective, evidence-based treatments to survivors.”

Last month, the psychiatric body quietly posted an apology on its website for “the harm experienced in state care” – which was criticised by one survivor as “an awkward and embarrassing failure”.

Coercion ‘needs to stop’

Last year, the World Health Organization issued guidelines on community mental health services.

The weighty document states the “perceived need” for coercion is built into mental health systems around the world, and reinforced through legislation.

“Coercive practices are pervasive and are increasingly used in services in countries around the world, despite the lack of evidence that they offer any benefits, and the significant evidence that they lead to physical and psychological harm and even death.”

Ferriss, of CCHR, says a review of mental health law should abolish compulsory or coercive psychiatric treatments, which can be brutal and punishing, in the public health system.

“The human cost is immeasurable.”

In December last year, the Abuse in Care Royal Commission released a two-volume interim report, He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu – From Redress to Puretumu Torowhānui.

It concluded New Zealand was a place of abuse and torture, where vulnerable and marginalised people were wrenched from families, cleaving cultural connections, based on a system of racism and discrimination.

The abuse included physical violence, rape and sexual violation, as well as painful injections of sedatives and electric shocks.

Some survivors, like Leoni McInroe, who spent 18 months, in two stints, at Lake Alice in the 1970s, felt re-traumatised by having to fight the Crown for compensation and accountability.

CCHR’s report details several deaths in state care – Michael Watene at Auckland’s Oakley hospital in 1982, after being given unmodified electro-shocks and high doses of psychiatric drugs, Watene’s cousin, Mansel, at Carrington Hospital in 1989, after a violent struggle and being injected with a sedative, and Dolly Pohe in Rotorua Hospital’s psychiatric unit in 1990, who was injected with a toxic level of drugs.

Inquiries suggested the deaths were avoidable, and noted mistakes and omissions. Some nursing staff were disciplined, or struck off, but none faced criminal charges.

Despite the cruelty and torture at Lake Alice in the 1970s, only one person, John Richard Corkran, has been charged. (The 90-year-old has pleaded not guilty.) And that only happened last year.

The unit’s former head psychiatrist, Dr Selwyn Leeks, died last year.

CCHR’s Ferriss wrote in his report: “What has been documented here is over 50 years of human experimentation, and excusing it as “standard practice”, and falsely asserting benefits that do not exist.”

The response of Government agencies – seen by many survivors as conspiring to defend their abusers, and limit their liability – over the next fortnight will, no doubt, be scrutinised closely.