The rapidly declining health of New Zealand’s marine environment raises serious questions about how we care for and manage the oceans.

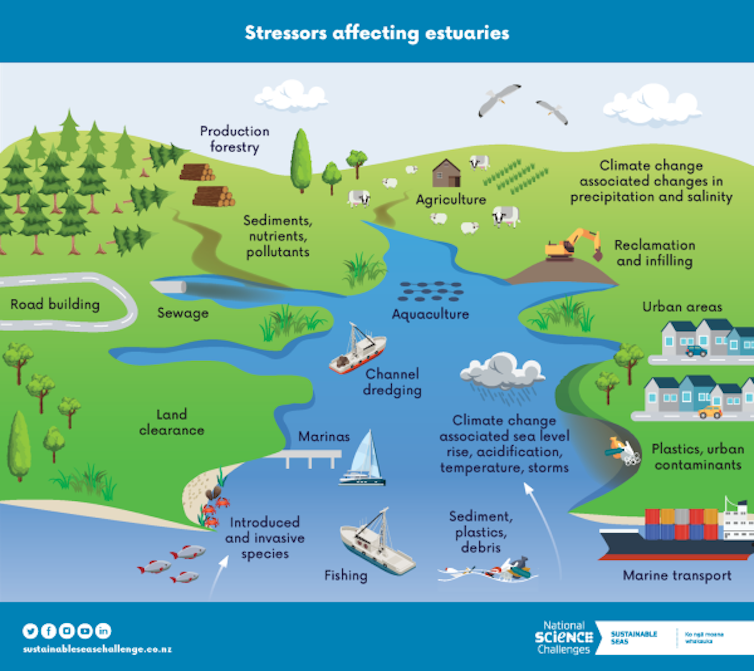

A recent stocktake of our marine environment identifies several cumulative pressures. These include ocean acidification, sea-level rise and ongoing warming of the ocean surface associated with climate change.

The report also highlights how activities on land lead to excess sediment, nutrients and plastic pollution flowing into the sea. Pressures at sea include fishing and aquaculture, extraction of natural resources, introduced invasive species and coastal development.

Our research explores the potential of ecosystem-based management – an approach that focuses on the whole system rather than individual species – to better regulate activities on land and at sea to improve ocean health.

We looked at what we would need in law and governance to support ecosystem-based management. We examined existing innovative forms of environmental governance such as legal personhood, community-based collaborative initiatives, policies that reflect Māori values and rethink our relationship to te taio, and management approaches led by kaupapa Māori.

We found we already have solid foundations to enable ecosystem-based management in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The state of our marine environment

Ecosystem-based management (EBM) emerged as an approach following concerns about declining biodiversity, fish stocks and habitats, as well as failures of sector-based governance arrangements to prevent environmental degradation.

EBM promotes a focus on ecosystems rather than on species. It seeks to sustain ecosystem health, integrity and resilience. It requires an integrated approach that takes into account social, ecological, cultural and economic impacts of multiple uses and stress factors.

An ecosystem approach can potentially reconcile conflicts between different user groups, resolve mismatches and fulfil sustainability objectives.

There are indications that some things may be improving. But the accumulation of sediment and the presence of heavy metals in estuaries are of ongoing concern. So is habitat degradation and biodiversity loss. Recent examples include the closure of scallop fisheries because of declining stocks.

A particular challenge is managing cumulative effects that arise from incremental or interacting stressors. These can come from human activities or natural events that overlap in space or time. Estuaries and coastal areas are often the final repositories.

Our understanding of the interaction between multiple stressors is still limited. Many arise from land-based activities and this makes regulation to protect the ocean challenging.

Changing environmental governance

Marine governance in Aotearoa New Zealand is characterised by fragmentation. Sectoral interests are regulated through multiple laws and policies. Responsibility for management is shared among at least 14 agencies operating under more than 25 different statutes across seven spatial jurisdictions.

The functions of these statutes range from regulating the effects of activities and access to resources to ensuring sustainable use and protecting species or areas of significance.

There are gaps in how land and sea are regulated. EBM, as an approach that benefits from mountains-to-sea thinking and action, could support more joined-up governance.

Environmental governance in New Zealand is already changing. Collaboration and place-based decision making are becoming features in new governance arrangements. How the environment is understood in relation to people, ecosystems and landscapes has also changed. It now better aligns with Māori worldviews and values.

We examined seven governance arrangements that span different environmental domains and reflect aspects of te ao Māori. We looked at marine and other examples to show what might be possible to enhance the implementation of EBM.

Two of the examples we examined are Ōhiwa Harbour and Kaipara Harbour. Both provide valuable insights into EBM in practice.

In both harbours, cumulative effects over multiple decades led to a decline in water quality and biodiversity and affected access to seafood.

In Ōhiwa Harbour, the decline in mussels and an over-abundance of seastars led to research and action focused on restoration and recovery. Scientists and tangata whenua worked together to improve management.

In Kaipara Harbour, concerns over ecosystem health led to the establishment of a co-management entity. The relationship between tangata whenua and the Kaipara Harbour is central to management.

Read more: Why Indigenous knowledge should be an essential part of how we govern the world's oceans

These are two examples of grassroots EBM initiatives involving tangata whenua, local councils, local people and central government agencies. Management practices are informed by science and mātauranga Māori and emphasise resilience rather than resource extraction and exploitation.

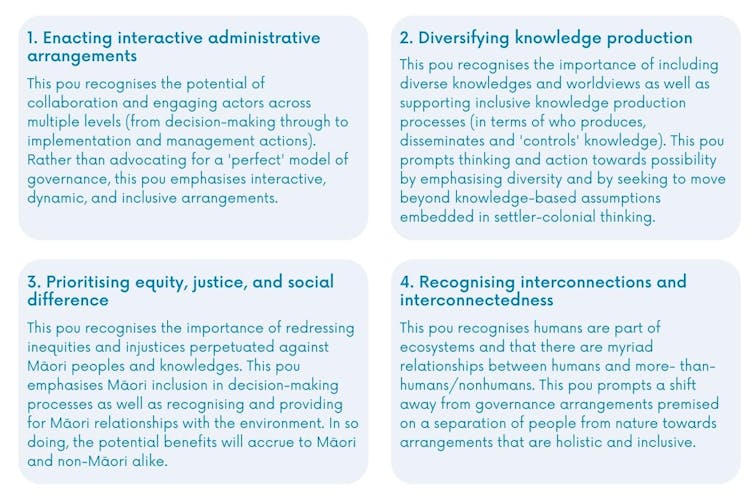

Based on these examples, we identified four pou (enabling conditions) to support the implementation of EBM with both Indigenous and non-Indigenous worldviews, knowledge systems and values.

Strengthening these pou would help governance by promoting collaborative and inclusive institutional arrangements capable of upholding Māori worldviews while being responsive to social and ecological complexity. These changes are already occurring. Focusing on how to support these changes ought to be a priority.

Karen Fisher receives funding from the New Zealand Ministry for Business Innovation and Employment (C01X1901) through the Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge’s Phase II Project 4.2 Options for policy and legislative change to enable EBM across scales.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.