How do you satiate the hunger of a supermassive black hole? With light-years-long rivers of cosmic dust, astronomers say.

Scientists have found evidence of remarkably long dust streams spiraling in toward the supermassive black hole living at the heart of our neighboring galaxy, Andromeda. It would appear that these giant streams quietly, but continuously, feed the cosmic abyss — and it's likely this has been going on for eons. The newfound streams illustrate how black holes billions of times heavier than our sun remain exceptionally quiet even as they gorge on nearby dust, gas and ill-fated stars. The findings owe themselves to scientists in Germany, Spain and Chile who analyzed archival images from NASA's now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope.

Supermassive black holes have previously been spotted feeding frenzies, gobbling such large chunks of glowing matter that their dark silhouettes shine brighter than entire galaxies chock-full of stars. However, the diets of other black holes, like the very quiet ones lurking in the hearts of Andromeda and our own Milky Way, have been unclear.

Related: Stunning image of Andromeda galaxy takes top astronomy photography prize of 2023 (gallery)

These silent beasts are fed by streams of gas spiraling into them slowly and steadily, with enough subtlety that rings of glowing material around them rarely fluctuate in brightness, according to a study published last year in the Astronomical Journal. This cosmic etiquette can be likened to water swirling down a drain, astronomers said on Thursday (May 9) in a NASA statement.

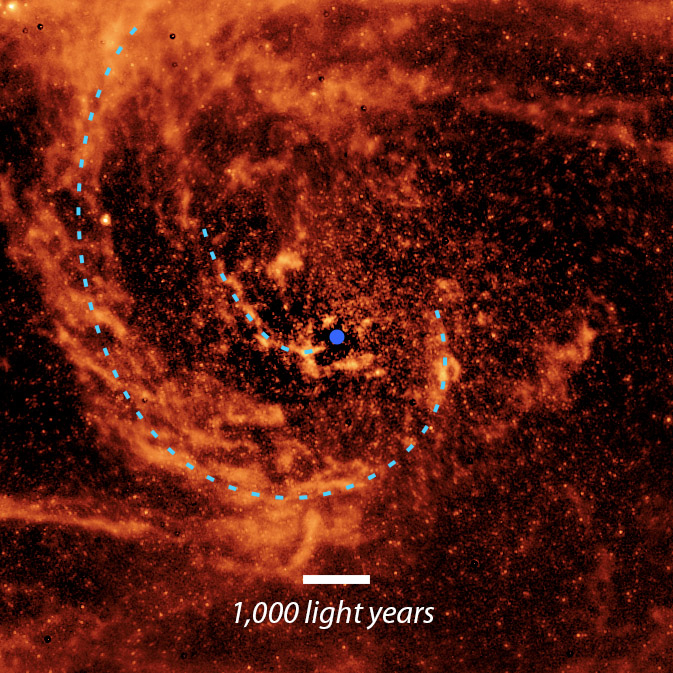

At about 2.5 million light-years from Earth, the Andromeda galaxy is the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way and one of the few galaxies visible to the unaided eye on dark, moonless nights. Unlike the distinctive spiral arms curved around the center of our own galaxy, Andromeda’s core is circled by multiple rings of dust.

To arrive at their conclusions, the astronomers first simulated how material around Andromeda’s black hole behaves over time. That simulation showed a tiny disk of hot gas may form close to the black hole, which would feed it before getting replenished by many other streams of gas and dust in the surrounding vicinity. Those streams, the researchers found, must be within a particular size and speed range to aid steady feeding, without which the black hole would belch and its brightness vary. Sure enough, when the researchers compared their findings to data from the Spitzer telescope, they found the telescope had already recorded spirals of dust within the required constraints.

"This is a great example of scientists reexamining archival data to reveal more about galaxy dynamics by comparing it to the latest computer simulations," study co-author Almudena Prieto, an astrophysicist at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands and the University Observatory Munich, said in the statement. "We have 20-year-old data telling us things we didn’t recognize in it when we first collected it."

The findings contradict some results from last year concerning a different group of astronomers who suggested all cosmic voids gulp nearby matter the same way irrespective of their appetite. The observed glow of matter being devoured by a hundred other supermassive black holes was "incompatible with an ordered flow of matter." Such contradictions allow astronomers to reassess what we know about black hole behavior.

NASA retired the Spitzer telescope in January 2020 after its 16-year tenure of collecting infrared data about comets and asteroids in our solar system, exoplanets beyond our solar system, and getting even deeper, various pockets of our universe clouded by interstellar gas and dust. The space agency essentially "replaced" Spitzer with the James Webb Space Telescope, which launched in 2021 and also sees the universe in infrared. In May of last year, however, the U.S. Space Force proposed a daring plan to resurrect Spitzer via a robotic mission to service the telescope and return it online, harkening back to the Hubble Space Telescope servicing missions. For context, Spitzer is now over 180 million miles (289 million kilometers) from Earth. Hubble was right in our planet's orbit.