Next to the Geminids of December and the Perseids of August, the most reliable of the annual displays of "shooting stars" are the October Orionids.

The Orionid meteor shower normally lasts from about Oct. 16 to 26. A few swift Orionids may appear as early as the start of October and a lingering straggler or two as late as Nov. 7. The numbers seen by any one observer tend to reach a maximum of around 20 per hour when conditions are clear and dark and the shower radiant point near the Orion-Gemini border is well up in the sky.

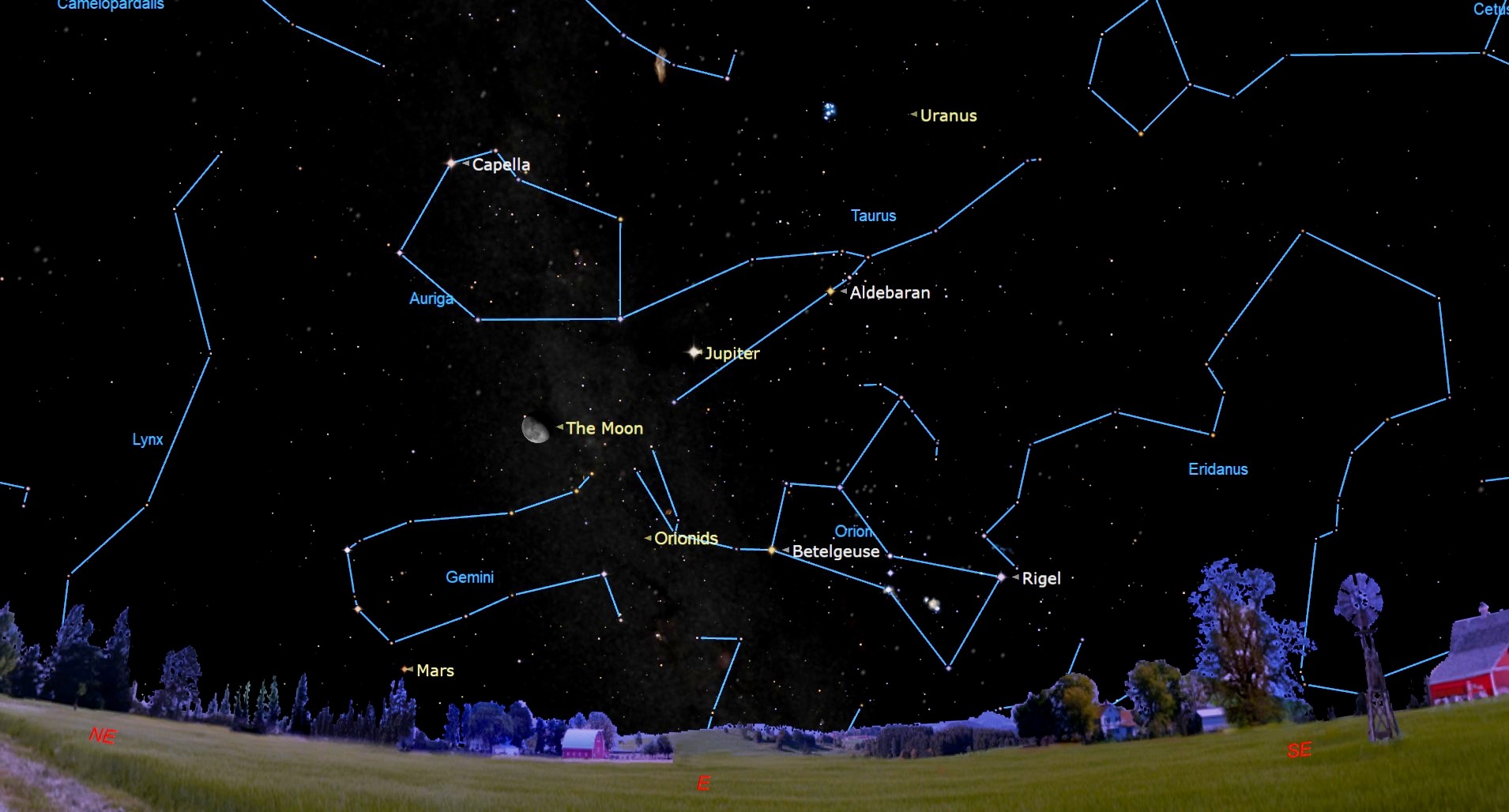

Unfortunately, this year, the Orionids are going to face a formidable handicap. When these meteors reach their peak early on Monday morning (Oct. 21), the waning gibbous moon will be in the sky almost all night long. Hence, its glare will severely hamper observations in 2024.

The meteors are known as "Orionids" because the meteors seem to fan out from a region to the north of Orion's second brightest star, the ruddy hued Betelgeuse.

Currently, Orion appears ahead of us in our journey around the sun, and has not completely risen above the eastern horizon until after 11:30 p.m. local daylight time. These meteors are at their best during the predawn hours at around 5 a.m. — Orion will then be highest in the sky toward the south. Since Orion's famous three-star belt straddles the celestial equator, the Orionids are one of just a handful of known meteor showers that can be observed equally well from both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

Usually Orionid meteors are normally dim and not well seen from urban locations, so it's suggested that you find a safe rural location to see the best Orionid activity. After peaking on Monday morning, activity will begin to slowly descend, dropping back to around five per hour around Oct. 25.

But the moon "muscles in"

Even though the moon already turned full this past week and is now on the wane, it will still have an adverse impact on this year's Orionids. On the morning of the Orionid maximum on Monday, it will be quite close to the star El Nath in the nearby constellation of Auriga; an 80% illuminated gibbous moon, flooding the sky with its bright light.

So although the Orionids will be at their peak, many of these streaks of light will likely be obliterated by the bright moonlight. Still, an exceptionally bright Orionid might still attract attention. Recent studies have shown that about half of all Orionids that are seen leave trails that lasted longer than other meteors of equivalent brightness.

Halley's Legacy

The Orionids are often referred to as the "legacy of Halley's Comet." In fact, these tiny flecks of dust are merely the cosmic litter that the comet has left behind in space along its orbit from previous passages around the sun.

Meteoroids that are released out into space are the remnants of a comet's nucleus. All comets eventually disintegrate into meteor swarms and Halley's is well into that process at this time.

These tiny particles — mostly ranging in size from dust to sand grains — remain along the original comet's orbit, creating a "river of rubble" in space. In the case of Halley's comet, which has likely circled the sun many hundreds, if not thousands of times, its dirty trail of debris has been distributed more or less uniformly all along its entire orbit. When these tiny bits of comet collide with Earth, friction with our atmosphere raises them to white heat and produces the effect popularly referred to as "shooting stars."

The orbit of Halley's Comet closely approaches the Earth's orbit at two places. One point is in the early part of May, producing a meteor display known as the Eta Aquarids. The other point comes in the middle to latter part of October, producing the Orionids. Step outside before sunrise during this weekend and onto much of next week, and if you catch sight of a meteor, there's about a 75 percent chance that it likely originated from the nucleus of Halley's Comet.

So, for folks like me, who desire to see Halley again, but probably won't (it won't be back until the year 2061) we'll have to settle for the Orionids as a consolation prize.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications.