The overprescribing of opioid painkillers in the UK is putting lives at risk, it has been warned.

Pharmacists have raised concerns about the powerful drugs ending up on the black market as patients are being given more than they need.

And a former addict has revealed how he manipulated NHS systems to obtain doses so high they could have killed him.

The drugs, including fentanyl, codeine, oxycodone, tramadol and morphine, can kill if a patient takes too many or if they fall into the wrong hands, they say.

A government-commissioned expert review of the overprescribing of medicines found last year it was at “unacceptable” levels, with as many as one in 10 medications handed out thought to be unnecessary.

Last year, prescriptions for fentanyl alone cost the NHS £34.5m, according to health service records.

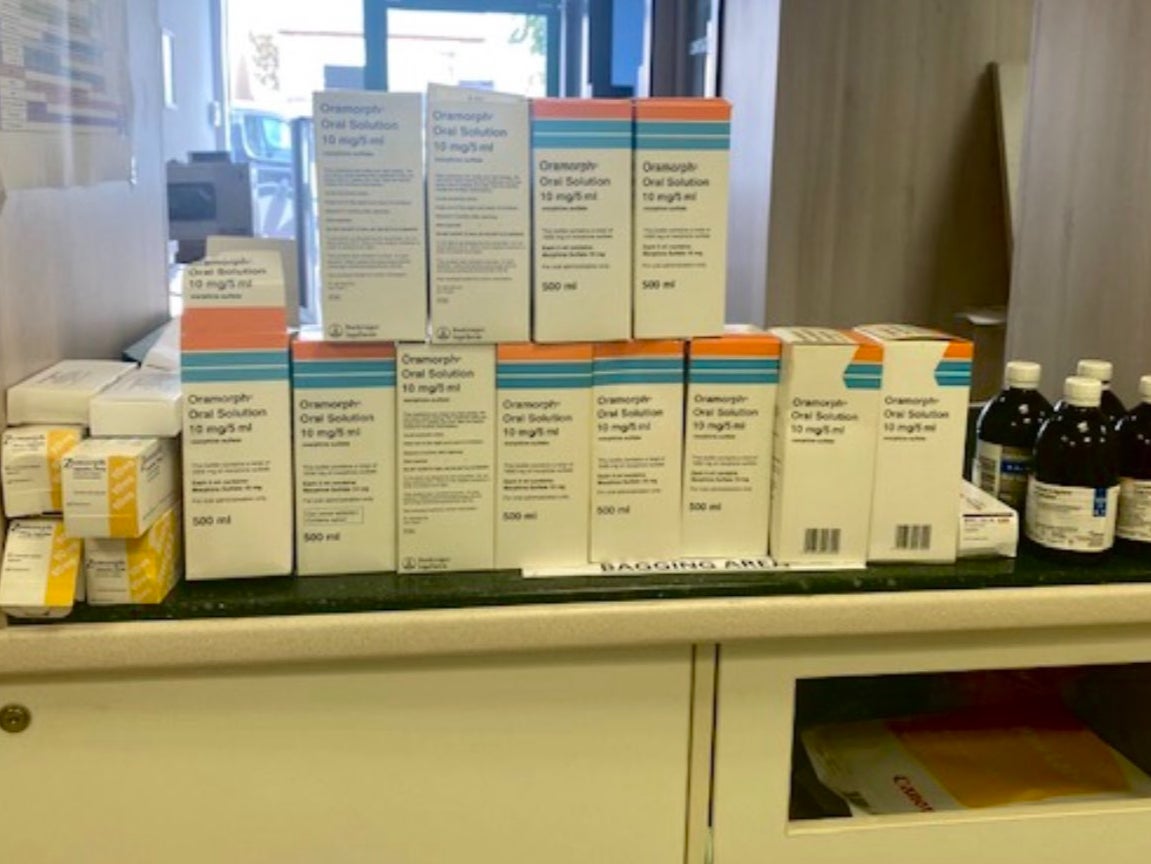

Leyla Hannbeck, chief executive of the Association of Independent Multiple Pharmacies, which represents community chemists, highlighted a case of one patient who returned to a pharmacy more than 30 prescription painkilling drugs, including 12 bottles of liquid morphine and 10 boxes of fentanyl patches.

Another patient handed in dozens of strips of high-dose morphine sulfate tablets.

Dr Hannbeck said that in both cases, the pharmacies had raised concerns about overprescribing with GP surgeries and informed local NHS teams “but to no avail”.

In the US, increased prescribing of such painkillers in the 1990s led to the country’s opioid crisis, with the widespread misuse of both prescription and non-prescription drugs, before it became clear how addictive they were.

Dr Hannbeck told The Independent that on many occasions pharmacists had raised concerns with local NHS teams over quantities of drugs prescribed but “not much has been done” and the problem had been worsening.

“On many occasions, it’s been raised but not much has been done,” she said. “Why is there no control? Why is no one listening?”

Dr Hannbeck said if drugs are not returned to a pharmacy for disposal they could end up contaminating the environment or falling into the wrong hands.

“Just imagine if they got onto the black market, for example,” the doctor said. “They could be very harmful.”

Former maths teacher Jada Woolf, 31, ended up with “bags and bags” of surplus co-codamol that were repeatedly prescribed even after she had switched to different painkillers for her endometriosis.

“Despite my regularly telling them that I wasn’t taking the co-codamol – after 18 months of having it slowly increased – every prescription included more of the stuff,” she said. “I ended up with bags and bags of extra ones.

“They just kept sending it with my repeat prescription, even when it had been agreed that it wasn’t on my prescription anymore.

Ms Woolf, who left teaching to run her own business, said she eventually stopped collecting the co-codamol from the chemist, leaving them to deal with the problem.

Adam Hardiman learnt how to manipulate the system to obtain more opioids than he needed when he became addicted to prescription OxyContin after bowel surgery.

Having spent 10 years on morphine, tramadol and codeine, he switched to the more powerful drug under specialist supervision, and said manipulating the system was very easy – he could go into any NHS walk-in centre, show them his stoma bag and request a prescription by telling them he was in pain.

On the same day, he could get a number of prescriptions and take them to different pharmacies or even use old prescriptions, enabling him to take at least four times his prescribed dose daily.

He would also ask his GP to write to his consultant to ask for more OxyContin.

The 39-year-old chef said the high was “unbelievable”.

“It made me feel like Jesus – completely at peace and everything was perfect,” he said.

But he warned: “Coming off it is 100 times worse than anything you have ever seen in a film or programme.

“After withdrawal symptoms start, you feel as if you are itching and burning from the inside. You get terrifying hallucinations, you can’t tell what is real, and the longer you wait to take it again, the more your body hurts until you literally feel you are going to die.”

Mr Hardiman, who blames drug companies rather than doctors for overprescribing, said a medically supervised detox and addiction treatment at Step by Step Recovery rehab centre saved his life, and he has now been clean for just over a year.

“I really think I would have died if I hadn’t gone,” he said. “I will continue for the rest of my life to attend meetings and follow the 12-step programme, but I am also living the best days of my life since I left rehab.”

Susan – not her real name – was given co-codamol after a home birth said she still takes those left over to help her relax.

“I take it when I want to feel zonked out or if I’m struggling to sleep,” she said.

She was prescribed 32 pills and took only four at the time but over the next 18 months, she took 17 more.

“Without wishing to sound flippant or make light of people with addiction issues, it is certainly moreish,” she said.

The mother-of-two keeps it secret from her partner.

“I keep quiet about it. I’ve maybe made a joke about enjoying my lovely codeine but I don’t think he realises that I actually would take it recreationally. I’d love to have a stash of more but I wouldn’t ask”

One pharmacist said practitioners are supposed to check opioid prescriptions with patients but don’t have time.

Another said some patients don’t want their doctors to know they’re not taking all their medication so stockpiles build up that are not down to overprescribing.

Professor Kamila Hawthorne, chair of the Royal College of GPs, said doctors were highly trained to take a holistic approach to caring for patients with chronic pain.

“GPs don’t want their patients to have to rely on long-term medication, particularly if there is a viable alternative, and most patients don’t want to be on long-term medication either.

“But access to non-pharmacological treatments and alternative therapies for pain is patchy across the country at a community level.

“Ultimately, we also need to see general practice equipped with enough GPs and other members of the practice team to sustainably deliver care to the growing numbers of patients that need it, including those on NHS waiting lists for treatments, such as specialist chronic pain services.”

After the 2019 expert review, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) introduced warnings of dependence and addiction on labels and safety leaflets for opioid medicines.

Janine Jolly from the MHRA said: “Opioids provide relief from serious short-term pain, but carry a serious risk of dependence and addiction, especially with prolonged use in non-cancer pain (longer than three months).”

An NHS England spokesperson said: “Local NHS services should offer effective pain management for patients, and review their medication on an ongoing basis, to ensure they are getting the care and support they need.

“Patients can access specialist care, including being offered alternatives to medication where this is appropriate.”