I don't think it’s all that controversial to say that the spirit of gravel is dead. As we've seen gravel racing get more professional over the years I'm hardly the first one to say that whatever the spirit of gravel is, it's gone. What I think might be more controversial is to say that not only is it dead but it's for the best. And the faster we accept that and support the reality of the times, the better.

Right now gravel racing is one of the few categories of growth in the American cycling scene. The gravel events and gravel bikes are exploding in popularity and yet, I rarely participate. When asked about it, I answer by saying I prefer not to drive to the ride and, if possible, I'll choose to leave my front door on a bike. I might also mention the price and how there's nothing stopping any of us from having a similar experience for free. Recently though, I realized those answers are excuses.

Going forward I'm going to replace my excuses with an honest answer. I don't often participate in gravel races because I can't win. And I don’t think I’m alone. Gravel racing needs categories 3, 4 and 5 so that more people have a shot at a podium.

A brief history of gravel racing

I'll leave the definitive history of how gravel racing evolved to others but it's still good to take a brief look at how we got here.

From my point of view, gravel racing evolved because of a mismatch between capable bikes and a desire to get away from cars and the roads well-travelled. It also evolved because of a rejection of rules.

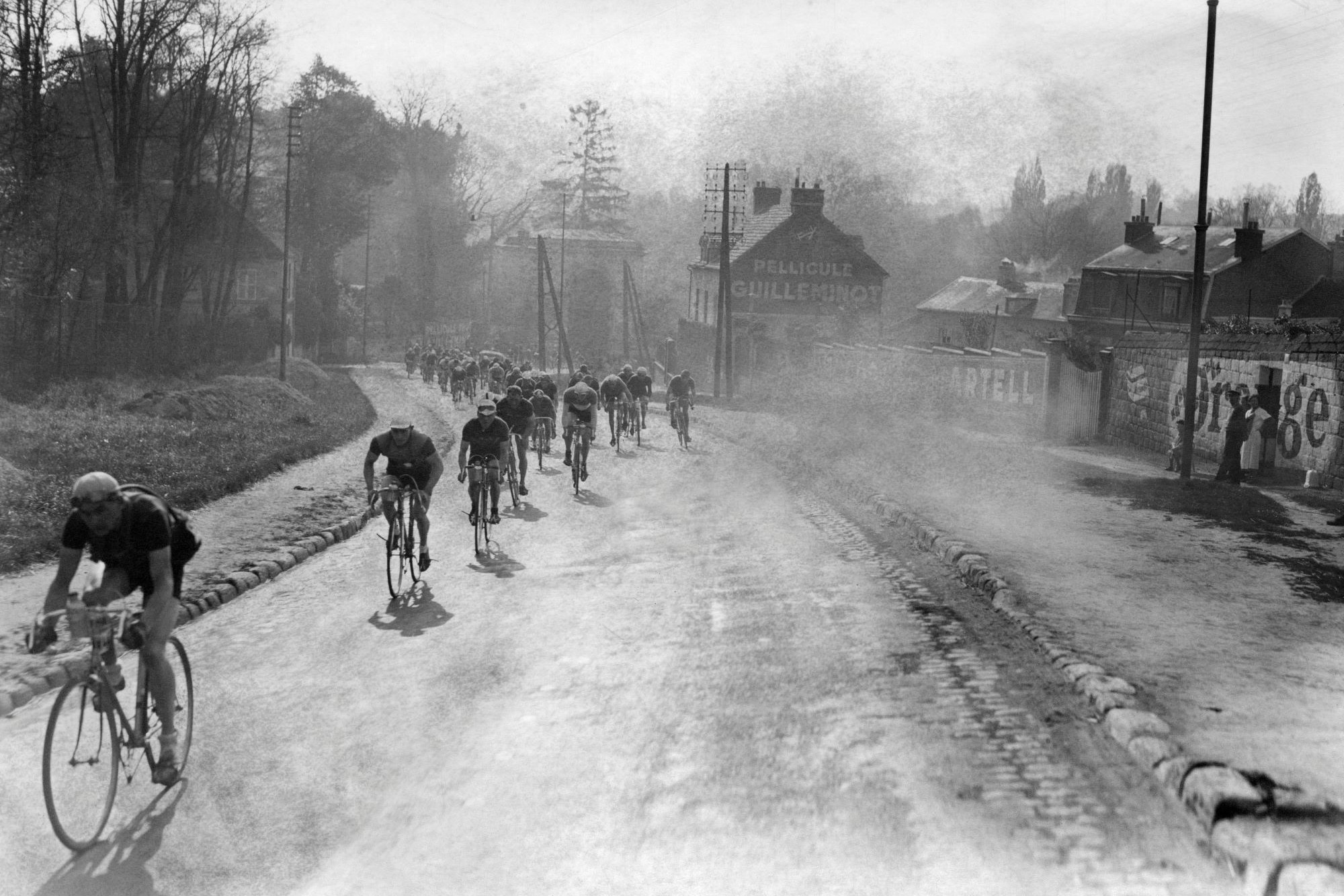

To start with, there are a lot of rules, both real and perceived, in road cycling. Those rules evolved out of previous evolution but those rules only work for people when there's a connection to history and a joy in celebrating a certain way of doing things. As the sport of road cycling grew in America, there became an ever greater disconnect between new riders and that history. The rules seemed stupid and it wasn't fun to be a part of them so people looked for something different.

If you want to rebel against rules, the most obvious way to do that is to have no rules and that's kind of what happened. Instead of pinning on a number and following a bunch of rules, people started to just go out the front door and see what kind of adventure awaited. Then, because there's always a push-pull between adventure and speed, those same people wanted to see who could do it faster. Back to numbers and rules until people forget why, again.

The most recent wave of rule rejection coincided with two other important cycling trends. The first is that American roads are continuing to get busier and more dangerous. As this happens, cyclists feel less safe and look to more remote places to ride. At the same time, or perhaps because of this trend, the technology of cycling is progressing and offering more options for bikes that feel like road bikes but with greater capability. Gravel bikes ride similar to a road bike but can take on rough surfaces that limit the number of cars.

So as people rejected the rules of road racing there was also a strong desire to get off the road and increasingly capable bikes emerged to cater to that desire. Unbound Gravel, previously known as the Dirty Kanza, began in 2006 so I'd say sometime around the turn of the century is probably when we started to see this evolution happening.

Meanwhile, on the hardware side, the first generation Salsa Warbird, Specialized Diverge and Cannondale Slate bikes hit the market in 2013, 2014 and 2016 respectively. Those are two of the earliest gravel race bikes and are likely a good proxy to the time period when gravel bikes started to really catch up to the trend of gravel racing. Or, said another way, that's around the time when gravel racing hit the big time. If you want to understand the spirit of gravel and the evolution of gravel racing, it’s the time between those two events.

Isn’t the spirit of gravel meant to be welcoming and all-inclusive first?

Between the turn of the century and the release of highly capable gravel race bikes, people used all kinds of bikes. Heading out on a road bike with rock hard, tubed 23mm tires to cover 100-200 miles of rough roads is just crazy and unpleasant. Early gravel cyclists laughed at the road riders of the day, with all their rules, and were happy to have a great time no matter how fast they were going — just finishing the day was a huge accomplishment no matter what. I'd call that the purest expression of the spirit of gravel. I'd also say that it is dead.

Today, we have incredibly capable bikes that are willing partners anywhere you'd like to go. Gravel bikes cover everything from drop bar mountain bikes to aero road bikes with bigger tires and everything in between. The choice is totally up to you. You can pick whatever makes sense for the type of ride, or race, you want to take on.

At the same time, gravel races are now highly professional. You aren't going out into the wilderness on your own anymore. There are now fully stocked aid stations, and cars to pick you up if you can't finish. Honestly, it's not that hard to finish a modern gravel race anymore.

Of course, there will always be beginners to the sport. This isn't meant to invalidate the experience of those who, rightly, feel like it's worth celebrating a finish at whatever distance makes sense to take on. More people on bikes is the goal and if you are just starting the journey, I'm so happy to have you. This is the same basic contract as a running marathon and there's absolutely nothing wrong with that experience. It's also worth noting that there are far more people who are happy to just finish than those who think it's easy or who are gunning for the top step of the podium.

I spoke at length with Chad Sperry from Breakaway Promotions and that is absolutely how he feels. Sperry has been in business since 2003 and runs a variety of successful events near me. He went to great lengths, even emailing me a follow up, to stress how important it was to him to help people comfortably enjoy the time they spend at his events. As we chatted, one of the things I jotted down was his comment that, he and his company feel that "bringing people together is the true spirit of gravel and that's reflected in the numbers. Success looks like more people into the sport."

That said, there are other experiences. I happen to fall into a group between those that celebrate finishing and those that could win. I don't think I'm alone and as a generation grows up with gravel racing, I suspect this group is only growing. Only focusing on either end of the participant spectrum leaves people out. Not only that but the more I write about it, the more it feels exclusionary. Isn't that the opposite of the spirit of gravel?

Gravel racing is at a crossroads

Gravel racing came into being because of a focus on being extreme. Today though, that's largely disappeared. The vast majority of gravel races are now single day events with value add propositions like food, drink, music and a brand expo. It's casual and fun yet also limited and expensive.

Take Unbound, for example. These days it takes nearly $2000 (in travel and lodging expenses) plus a minor miracle to get an entry to partake in the Kansas event. That's quite a far cry from the days when a group of friends set out to race themselves across the Flint Hills.

Still, this is what gravel looks like these days. It's road racing on different terrain. And that's fine, but there has to be a reason for folks to return year after year. Completing the event, in itself, is not enough of a challenge. I think it's time for gravel to introduce lower categories so that people, like me, can have the opportunity to compete in the 100-200-mile one-day format that has become a standard.

I ride five days a week, including one 100-mile ride every weekend. Still, I'm not even close to the four-hour mark that would put me on the 40-50 age category podium at the nearby Gorge Gravel Grinder race.

In other disciplines of racing, the categories 3, 4 and 5 exist for the everyday avid riders. Those people who are fast-ish and like to compete but also have work, family and other priorities. Being able to compete with my peers in these categories would be very intriguing to me.

The danger in categories

Now, I’ve spent a lot of time advocating for something I want but I also want to be mindful of those who aren’t in the same place as me with their riding.

I’ve already mentioned how valid and important the experience of finishing a race is for those that find it a challenge. I don’t want to take away from that at all. I also want to be careful about shaming those who simply enjoy a day on a bike at an event.

In sharing my views with Sperry, he gave me a word of caution.

“In the end the only person that is truly happy in this format is the person on the top step. Even second and third place tend to have sad expressions standing on the podium wondering what they could have done more to achieve that number 1 spot,” he said.

"For us the journey is just as important as the finish. At this time that seems to be what the majority of people want. They want an experience or an adventure over a 1st, 2nd, or 3rd place medal.”

So perhaps I’m wrong or simply in the minority. I’d like to compete but I wouldn’t be taking it too seriously. The possible podium would be a reason to show up but a loss wouldn’t be a reason to have a bad time. Right now, I get that experience on Zwift and maybe that’s where that type of competition for fun belongs, while gravel racing is an opportunity to enjoy "the spirit of gravel." Somehow that seems like a loss though, am I wrong?

After more opinions on the direction of gravel? Try: 'The UCI doesn’t have anything to offer the gravel community that it doesn’t already have'