It’s abundantly clear that the 60s were a time of boundless innovation, that forward momentum was at a premium and that the future couldn’t happen quickly enough. Yet while the decade sired countless albums of influence, no single recording sounded more like a portal into the future than The Stooges’ self-titled debut.

The Stooges had formed in Ann Arbour, Michigan, close enough to Detroit to become immersed in the city’s burgeoning musical culture. Aside from Berry Gordy’s all-conquering Motown label, rock’n’roll show bands (all synchronised dance steps and explosive energy) dominated a vibrant live circuit.

Compelling performers like Mitch Ryder And The Detroit Wheels captured the imagination of a young drummer called James Newell Osterberg who’d experienced an epiphany witnessing a soundcheck by The Decibels, featuring Bob Seger, at high school: “I’d never heard a Fender Twin Reverb turned up past five before and it just intoxicated me. It was the fucking devil.”

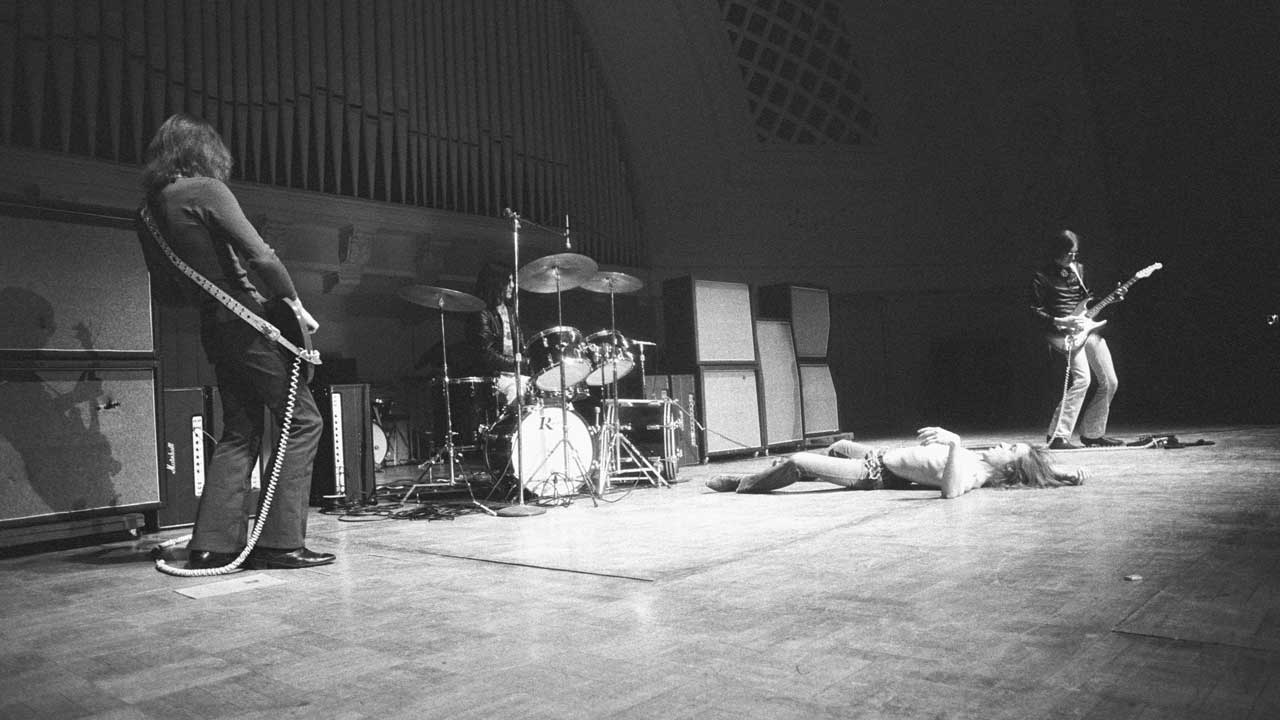

Osterberg latterly joined The Iguanas, so his next band, The Prime Movers called him Iggy. On switching to vocals, Iggy formed the Psychedelic Stooges with ‘high school drop-outs’ Ron Asheton, Scott Asheton and Dave Alexander, who called him Pop, and set about reinventing the blues. Upon gaining a reputation for unpredictable live performances, the band were snagged for Elektra by Danny Fields – who was in Detroit to witness the MC5, but equally entranced by their support band.

One of the reasons The Stooges’ debut record sounded so fresh, new, immediate and raw is because that’s exactly what it was. When the band entered New York City’s Hit Factory studio in April ’69 with producer (recently ex-Velvet Underground alumnus) John Cale, they only had five coherent songs: 1969, I Wanna Be Your Dog, No Fun, Ann and We Will Fall.

“Before we were a straight rock’n’roll band we were very experimental,” understates Iggy. “At our first gigs we had instruments onstage I invented from things I found in junk yards… I wore white face paint, an aluminium foil Afro wig, never spoke and never had a written lyric. Until we recorded our first album there was no written or repeated Stooges song.

"Shows were a stream of consciousness. I ordered the band never to end a song because I didn’t want people to have a chance to accept it or not. That’s when we instituted leaving in a hail of feedback. If it was still feeding back we could get off the stage before they had a chance to do anything about it.”

Once recorded, and even with We Will Fall stretched out to over ten minutes, they still had only 25 minutes of music in the can and Elektra weren’t impressed. Consequently, the band had to write three more songs overnight. Real Cool Time, Not Right and Little Doll might have been conjured up on the spot, but stood the test of time.

While The Stooges – now weighing in at a slimline 34 minutes – sizzled with electricity throughout its eight-track duration, it boasted two particular songs that between them provided a perfect blueprint for rock’s future. I Wanna Be Your Dog and No Fun preceded and precipitated glam, punk, grunge, alt.rock and much else with a sullen streetborn simplicity, an unprecedented level of unrepentant nihilism and juvenile delinquency that, in the case of the entirely timeless Dog, oozed with a tangible undercurrent of dark, forbidden sex.

I Wanna Be Your Dog was, in the best meaning of the word, filth. If you could listen to it without craving instantaneous physical gratification, there was probably something wrong with you. No Fun meanwhile, leant on a muscle car reeking of Thunderbird wine – the ultimate four-chord ‘fuck-you’. When the Sex Pistols briefly dropped their carefully constructed year-zero guard in ’77 to hijack it for Pretty Vacant’s b-side it defined them perfectly. Strip away the safety pins, sneers and haberdashery, and No Fun’s legacy runs through punk like a spine.

The Stooges was the sound of industrial Detroit, its revolutionary fervour matching its politicised time. With Motor City burning, the Vietnam draft and civil rights at the forefront of youth consciousness, The Stooges’ debut mirrored the existential angst of a newly radicalised generation in turmoil. Urban desperation defined in a compelling hybrid of garage rock brevity and free-jazz autonomy, edged into the arena of genius by the mesmeric drones John Cale co-opted from New York’s avant garde, developed with the Velvet Underground, and perfected with I Wanna Be Your Dog’s nagging one-note piano riff and insistent sleigh bells.

The Stooges’ idiot-savant combination of simplicity and swagger rivals Ramones as the ultimate example of no-fat, frill-free, D-UM-B brilliance. Teen inarticulacy distilled to its volatile essence, restless adolescent boredom as a fine art. Dean’s Rebel Without A Cause, Brando’s Wild One, My Generation’s stuttering pill-blocked narrator, recast for a newly disillusioned constituency of Altamontbound cannon fodder in the person of Iggy Pop.

Iggy’s firecracker instability counterbalanced the thuggish reliability of guitarist Ron Asheton, his younger brother Scott (drums) and bassist Dave Alexander – a man so dedicated to the hoodlum lifestyle that he dropped out of his senior high-school year after 45 minutes in order to win a bet. Together they unleashed The Stooges, punk rock’s crucible, the sound of four unlikely visionaries staring down the barrel of an uncertain future.