It is Thursday May 20, 2021, and Campbell Flynn – “tall and sharp at fifty-two […] a tinderbox in a Savile Row suit, a man who believed his childhood was so far behind him that all its threats had vanished” – makes his way along Piccadilly to sign copies of his latest book, a life of the painter Vermeer that the Financial Times has declared “a work of mesmerising empathy”.

Famously, almost nothing is known about Vermeer’s life; all we have is the art. We might say the same about Campbell. We are not sure who he is. There is only artifice, the performance of roles: husband, father, commentator, celebrity professor. In lifelong flight from his impoverished upbringing in Glasgow, he has made a career of surface, gesture and interpretation.

But something, Campbell senses, is “off”. He feels like he is “steering gradually towards a precipice” .

Review: Caledonian Road – Andrew O'Hagan (Faber)

Caledonian Road is a dazzling state-of-the-nation novel that follows Campbell as he approaches that precipice over the course of 650 pages. Andrew O’Hagan offers a mordant critique of the overlapping lies of solidarity and competence that put a typically English-public-school spin on the twin catastrophes of Brexit and COVID. Britain, it turned out, was run by people like Campbell: invested in surface, gesture and interpretation.

Things really began to give during the mismanaged COVID lockdowns (I was there). Ordinary Londoners tried to keep track of the changing rules for social gatherings and took rationed walks around empty playing fields, while ambulances ferried the dying to emergency wards – and politicians partied.

O’Hagan offers a portrait of this great unravelling. His novel follows a dizzyingly diverse cast of characters whose lives are entangled along a single London thoroughfare.

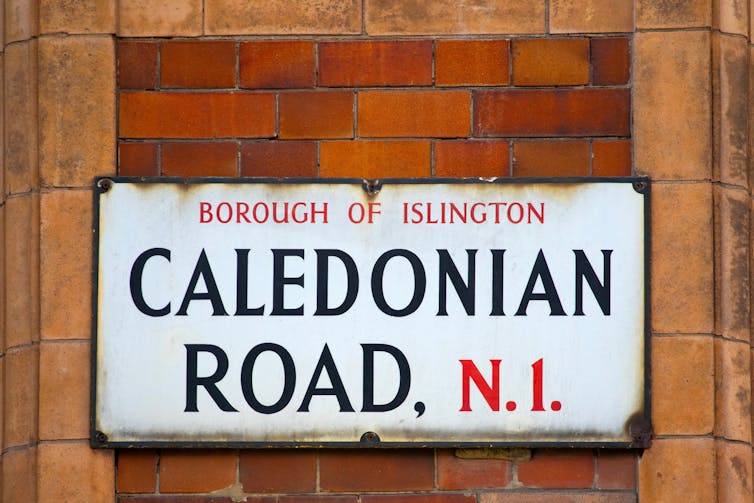

Caledonian Road runs south-north through Islington, from King’s Cross to the junction of the Holloway and Camden Roads. Unexceptional in many respects, “Cally” is paradigmatic in others – indeed, it served as a London example in the 2012 BBC documentary The Secret History of Our Streets. O’Hagan, Glaswegian himself, perhaps also appreciates the street name’s nod to his homeland.

Like many major arteries, along its short, mile-and-a-half length Caledonian Road passes both smart Georgian terraces and depressed housing estates, restaurants the English like to term “ethnic” (Ethiopian in this case), and flashy shops attracted by the King’s Cross Central developments that landed Google’s Europe HQ in the vicinity.

Also nearby is Pentonville Prison, which is not strictly a panopticon, as O’Hagan’s narrator alleges, but a useful metaphor nonetheless for the novel’s omniscient style – and for its characterisation of almost every aspect of this society as broadly, in one sense or another, criminal.

Merciless satire

Caledonian Road differs from novels with a comparable conceit – John Lanchester’s Capital (2012), for example, which also visited residents on a single road in South London in the wake of the global financial crisis – in that its canvas is much broader, its aim sharper, its satire merciless.

O'Hagan’s ear for dialogue is impeccable, too. A po-faced academic at one point is said to have written a study of street-language in Oliver Twist. One senses O’Hagan could do it just as well. Caledonian Road contains broad Ayrshire, Roadman’s slang, Polish-accented English, the bluster of ex-military club men, the earnest platitudes of Gen-Z bloggers (who “flitted in and out of everybody’s life as if permanence was a conspiracy supported by old people and their nostalgic governments”), and the clipped put-downs of the landed classes.

Among the latter is Campbell’s wife Elizabeth, a therapist and daughter of minor aristocrat Emily (gifted some of the funniest quips in the novel). Elizabeth’s sister has married a Duke, a boorish man, who, like many in his circle, is not above involvement with Russian money of dubious origin.

We also meet Aleksandr Bykov, a ruthless Russian billionaire and father to the foppish Yuri, “elegant, camp, with short, peroxided hair”. Yuri offers a pitch-perfect sketch of how dirty money was laundered through the arts in early 21st century Britain. Publicly an art dealer, in secret Yuri bankrolls people-smugglers, importing undocumented Vietnamese and Polish sweatshop labour to service garment manufacture and marijuana greenhouses. He has “the habit”, the omniscient narrator observes,

common to first-generation English Russians, of taking the high life for granted; the thing he didn’t take for granted, but was driven towards like a sniffer dog, was the low life of the United Kingdom. […] Where his father and his friends wanted the imprimatur of Ivy League universities, dinners with princes, a club membership or a gong from the Queen, Yuri wanted, more than anything, the attention of meatheads and drug dealers, hookers and party boys, art-crook impresarios and online pirates. He was born to it, in a way he couldn’t quite explain but which gave him a feeling of power.

One of the beneficiaries of the Bykovs’ illicit activities and dangerous loans is Campbell’s longtime friend, retail tycoon William Byre, whose wife, Antonia, writes outrageous right-wing columns for the Guardian-like Commentator, as a foil to the newspaper’s otherwise decidedly liberal agenda. William’s “moral arbiters” are said to be “only the market and his own ambition”. His empire begins to crumble when allegations of pension-fund fraud emerge, augmented by more terrible allegations as the novel progresses. Surely no resemblance to recently notorious figures is intended.

Interconnected worlds

Byre’s son, Zak, who bears some resemblance to another famous scion with green aspirations, moves in the same circles as Campbell and Elizabeth’s children: Kenzie, a sensitive lesbian, and Angus, a raucous celebrity DJ. He is also acquainted with Yuri and the young Commentator journalist Tara Hastings, whose reporting leads to several sub-plots’ denouements. “All these worlds are interconnected”, observes Campbell as the nets begin to draw around him.

One of those nets is of his own making. Having accepted loans from Byre, Campbell attempts to make a quick killing by publishing a rage-bait book about modern masculinity called Why Men Weep in Their Cars. Its ironic intent is, however, misread by the beautiful young actor – one of Yuri’s hangers-on – who accepts the commission to pretend to be the book’s author. He turns it into a (white) male-lives-matter moment, with spectacular consequences.

Campbell’s teaching post in UCL’s English Department, where his colleagues resent his public-intellectual status, places him on a collision path with a bright young computer science student named Milo Mangasha, the son of an Irish cabbie father and Ethiopian-born schoolteacher mother. Campbell sees something of himself in Milo – “The boy was working class, like Campbell used to be” – and is willingly drawn into a relationship of mutual education. Milo becomes the novel’s foil to Campbell’s self-assured position of cultural capability.

Milo is also a hacker-extraordinaire – much of Tara’s information comes from him. His apprehension of the connected worlds of London’s privileged allows him to advance his own plan to avenge the death of his mother, a casualty of COVID during the worst of the lockdowns, and by extension his side of the Caledonian Road community.

To the politicians who flout their own rules, to the Establishment who backs them up, Milo swore revenge. To the liberals who think they do well by managing language, giving up nothing while they spell out the difference between one grain of sand and another, he swore exposure. Milo understood as the year went on that nothing for him could ever be the same.

As the year goes on, Milo’s plots become more elaborate. All the while, the fates of his childhood friends, who live in housing estates along Caledonian Road, confirm the ongoing nature of structural violence. In depicting their crises, and those of the smuggled immigrant workers, O’Hagan’s writing is especially poignant. The commitment of Milo’s friends to drill rap, reputation, sneakers and drugs fails to salve a deep pain that comes from marginalisation and its legacies.

Here, too, Campbell is more like his near neighbours than he knows. And there is another near-neighbour (literally) beneath his feet: the elderly protected tenant who lives in a cold, filthy flat beneath the Flynn’s multi-million-pound Georgian terrace on Thornhill Square. Her entanglement with Campbell’s life leads to another showdown.

At one point, Milo pores over Charles Booth’s London Poverty Maps and sees that the extreme variation in wealth and poverty around him is just as it was in the 19th century. Booth is one of the novel’s numerous intertexts. I mentioned Dickens earlier; there are many such asides, confirming for the alert reader Caledonian Road’s debts not only to Dickens, but Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies (1930), Émile Zola, Henry James, Ralph Ellison, Lionel Trilling and E.M. Forster.

During his dissolution Campbell utters a line – “Only disconnect” – that readers of Howard’s End (1910), Forster’s great novel of the liberal temperament (as a defence against the New Money), will recognise as a parodic inversion – “only connect” is the original. Campbell is punning on unplugging from the web. But the phrase could be interpreted as a recognition of the futility of trying to disconnect from the web of complicity that ensnares us all.

It is, appropriately, in relation to a painting that Campbell expresses the opposite sentiment early in the novel, in a line that is perhaps the novel’s ultimate injunction. Looking at an image of Glaswegian boys playing and noting “the damage in the children’s eyes”, Campbell muses: “In order to have a good life […] you have to fix all of this and make change.”

Andrew van der Vlies does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.