Nothing lasts forever, including the stars in our night sky. One of the brighter and more notable stars in our sky is Betelgeuse, the bright red supergiant in the shoulder of Orion.

In late 2019, astronomers around the world grew giddy with excitement, because we saw this giant star get fainter than we’ve ever seen it before. Since Betelgeuse is at the end stages of its life, there was some speculation this might be a death rattle before the end.

But the cause of the “great dimming” wasn’t entirely clear until now. New preprint research awaiting peer review, led by Andrea Dupree from Harvard & Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics, has used the Hubble Space Telescope to help uncover one of the biggest astronomical mysteries this century – the cause of Betelgeuse’s sudden strange behaviour.

Read more: Betelgeuse: star's weird dimming sparks rumours that its death is imminent

A star on the brink of death

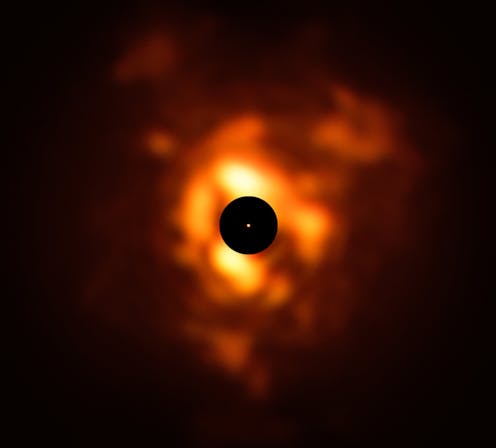

From this latest research, it was discovered that in 2019 Betelgeuse likely underwent an enormous surface mass ejection (SME). An SME happens when a star expels large amounts of plasma and magnetic flux into the surrounding space.

We don’t fully understand what caused this SME, but if they have similar progenitors to the coronal mass ejections we’ve seen on our own Sun, they might be caused by the destabilisation of large-scale magnetic structures in the star’s corona.

It is suspected that Betelgeuse lost a large part of its surface material in this remarkable event. In fact, the amount of material ejected is the single largest SME event we’ve ever seen on a star, in modern astronomy.

What is truly remarkable is that Betelgeuse ejected 400 billion times more mass than a typical event on other stars. This is multiple times the mass of the Moon, pushed out at incredible speeds.

Stellar evolution in real time

Betelgeuse is much like an astronomical jack-in-the-box. Astronomers know that sooner or later it will “pop” and implode in a spectacular supernova, but we don’t know when. (We do know that when it does, it might even be visible in the daytime sky!)

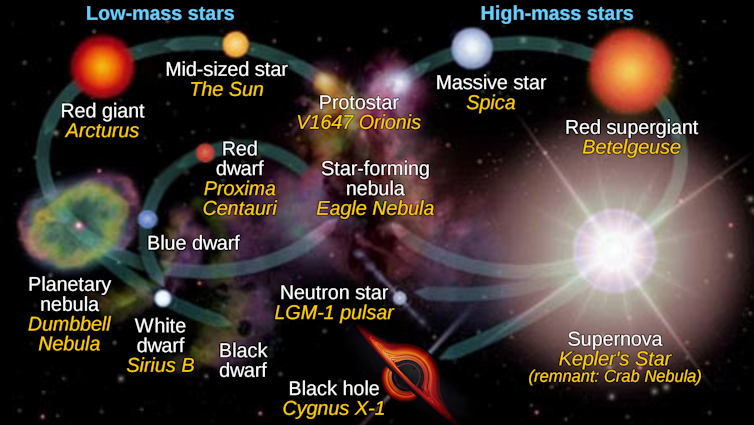

Stars are born in many different sizes; some start small and become big, while others are born big. Betelgeuse is a red supergiant and would have started out smaller, before expanding its outer shells over tens of millions of years. Once large, red supergiants don’t have very long until they reach a point where their cores produce iron and can no longer sustain nuclear fusion.

We’ve seen the deaths of many thousands of distant stars before, in galaxies far, far away. But the allure to study the process in near real-time on our galactic doorstep is too good to pass up. In our stellar neighbourhood, Betelgeuse offers us the best chance for success.

We have pieced together the secret lives of stars by studying things like globular clusters, distant supernovae and stellar nebulas. From these, we can understand the birth, life and death of a star.

However, there are often gaps in between. Betelgeuse is giving us a glimpse into the “before” of a star’s end, the final tens of thousands of years before the big event – a mere eyeblink in astronomical terms.

Already from this latest result we are beginning to better understand how large stars like Betelgeuse lose mass through surface mass ejections as they age. As Dupree explains:

We’ve never before seen a huge mass ejection of the surface of a star… It’s a totally new phenomenon that we can observe directly and resolve surface details with Hubble. We’re watching stellar evolution in real time.

Surprising aftermath

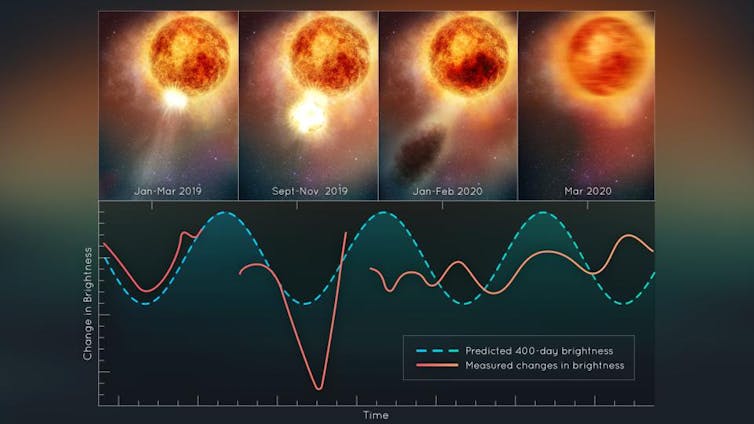

One of the most interesting things we’re seeing from Betelgeuse in the aftermath of its surface injury is a significant speed-up in its pulsation rate.

For more than 200 years, astronomers have faithfully tracked the brightening and dimming of Betelgeuse, using its very constant 400-day cycle.

The massive ejection of material may have disturbed the entire internal structure of the star, with inner layers possibly sloshing around and disrupting its typical pulsation rate.

Time will tell if it can recover to pre-ejection pulsation, as we continue to monitor the brightness of Betelgeuse closely.

Although we do not think Betelgeuse is ready to die just yet, we wouldn’t know it actually has until roughly 640 years later. Thanks to the constraints of the speed of light, everything we see in the cosmos is a glimpse back in time – even the stars in our night sky.

Read more: Stars that vary in brightness shine in the oral traditions of Aboriginal Australians

Sara Webb does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.